calsfoundation@cals.org

Civil War Pensions

The granting of pensions for military service presented unique problems to the ex-Confederate states and the federal government after the Civil War. Before the war, small annual pensions and land grants had been given to qualifying veterans of the U.S. military who had served in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, and the Mexican War. What originally began as limited payments to former soldiers (and their widows and orphans) eventually became a huge federal bureaucracy of old-age pensions for almost one-third of the elderly population of the United States.

Burdened by fraud, the two Civil War pension systems were not alike. Union veterans applied for their monthly payments under a federal pension system. Ex-Confederate soldiers had to look to the individual states in which they served during the war. The federal government began paying Union veterans pension payments as early as 1861. It was not until the early 1890s that all eleven of the former Confederate states created and funded their own state pension programs for Confederate veterans. The states agreed that pensions paid to former Confederate veterans would be paid by the state in which he and his widow lived, rather than from the state in which he served. Until that time, all the states had to offer were artificial limbs and veterans’ homes for the indigent.

In 1890, Congress enacted a new law that paid a pension to any Union veteran of the Civil War who served for at least ninety days, was honorably discharged, and suffered from a disability, even if not war-related. In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt, himself a veteran of the Spanish-American War, ruled that old age itself was a disability, thereby increasing the number of eligible veterans for pension payments.

At its peak, the Civil War pension system consumed approximately forty-five percent of all federal revenue and was the largest department of the federal government (other than the armed services). One reason for this was the political power held by Union veterans’ groups like the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), which had been founded in Illinois in 1866. At its peak in the 1880s, the GAR had a membership of more than 400,000, and it was said that no presidential candidate could gain the Republican presidential nomination without the blessing of the GAR. Its counterpart, the United Confederate Veterans (UCV), was not formed until 1889 and never had the political sway over national politics enjoyed by the GAR.

Arkansas was one of the first of the Southern states to grant annual pensions to resident ex-Confederate veterans and their widows with the passage of Act 91 by the state legislature on April 1, 1891. Act 91 created a State Board of Pensions composed of the governor, the attorney general, and the auditor of state. Local county pension boards oversaw the granting of pension applications. Some 45,000 Confederate veterans and widows of veterans received benefits under the provisions of the act until the creation of the Arkansas State Department of Public Welfare in 1939. At first, only needy, indigent, or disabled veterans who had been honorably discharged—or unmarried needy or indigent widows of veterans—were eligible for Arkansas Confederate pensions. Beginning in 1913, needy widows who had not remarried (and who were born before 1878) and widowed mothers of veterans, were added to those who could file for benefits. Those veterans who lived in the Arkansas Confederate Home in Sweet Home (Pulaski County) were not eligible to receive pension benefits.

From 1891 until 1913, the annual Arkansas pension payment to Confederate veterans and widows was $25 to $100, depending on their circumstances. In 1913, the amount was raised to $100 per year for all classes of pensioners. Inadequate state funding prevented most pensioners from receiving their full yearly payment. Applications for the pension payments had to be submitted to the county boards before July 1 each year.

A pension file included an application form signed by the veteran or his widow, a doctor’s certificate of disability, and a statement of indigence. The file also usually contained two affidavits from “comrades at arms” attesting to the veteran’s military service. (In contrast, Union veterans did not have to give these affidavits from former comrades. They only had to list the company and regiment from which they served. Most official Union records survived the war, while many Confederate service records did not.) A widow’s application might contain information on her husband’s death even though the information could be very sparse due to the lack of records.

Today, the Confederate pension files are a part of the Arkansas State Archives collection in Little Rock (Pulaski County). All of these files have been microfilmed and are available to the public for research purposes.

The following are examples of Confederate and Union soldiers receiving pensions.

The Case of Confederate Veteran Wilber Jacob Ridling

Wilber Jacob Ridling, age twenty-five, was a farmer who lived just outside Camden (Ouachita County) when the war began. He enlisted on September 1, 1861, in Company B of the Sixth Arkansas Infantry, Hindman’s Brigade, Cleburne’s Division, Hardee’s Corps in the Army of Tennessee. He fought in several battles throughout the war, including Shiloh, Missionary Ridge, and the battles of Atlanta, Franklin, and Nashville. After the battle of Nashville and the Confederate retreat into Mississippi, Ridling was able to secure a furlough and return home to Arkansas. Upon hearing of Robert E. Lee’s surrender, he went to the fort at Camden, where he was surrendered with the post.

After the war, Ridling moved to Texas and returned to farming. He attended several reunions, including the Confederate Reunion in Dallas, Texas, in 1902. He was living in Plaxeo, Texas, when he filed his application for a Confederate pension with the State of Texas in April 1902 for his service with the Sixth Arkansas. He testified that he was disabled and had been unable to farm for six and a half years. He claimed he owned no real estate and no personal property. A local doctor also supplied an affidavit as to Ridling’s current medical condition. In addition, Ridling provided affidavits from two living witnesses to his Confederate military service—B. A. Hicks of Morrilton (Conway County) and cousin M. F. Ridling of St. Vincent (Conway County). Both men testified that the claimant had served with them throughout the war. Ridling’s application for a pension was approved in July 1902, and he received an annual payment of $31.60, which slowly was increased by the State of Texas throughout the years. When he died on July 18, 1916, Ridling was receiving $63 as an annual pension for his Confederate service.

The Case of Union Veteran Edward Clanton

Edward Clanton served in Company L of the First Arkansas Union Cavalry for three years. While farming near Hogeye (Washington County), Clanton, thirty-one, had to hide out from bushwhackers for more than three months. He finally made his way to Springfield, Missouri, where he enlisted on August 16, 1862, with the First Arkansas Union Cavalry, rising to the position of wagoner for the entire regiment (while only carrying the rank of a common private). Clanton’s muster-out papers contain the information that he bought his saber, his saber belt, and belt plate, as well as the unusual Pettingill .44 revolver he carried throughout the war. Clanton also attended several regimental reunions that were held in Arkansas and Missouri.

He applied for a pension on July 14, 1890, through the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Pensions in Washington DC, while living on his farm near the town of Cassville, Missouri. His physician, Dr. Jell Martin, testified through an affidavit that Clanton was suffering from rheumatism and that he had suffered with it during his military service and ever since the close of the war. The former soldier received $8 a month for his pension. In 1912, Congress raised the monthly pension to $30 a month, or $360 a year, for Union Civil War and Mexican War veterans.

For additional information:

Bishop, Albert W. Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Arkansas for the Period of the War of the Late Rebellion, and to November 1, 1866. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1867.

Glasson, William H. Federal Military Pensions in the United States. Edited by David Kinley. New York: Oxford University Press, 1918.

———. History of Military Pensions Legislation in the United States. New York: Columbia University Press, 1900.

Neagles, James C. Confederate Research Sources: A Guide to Archive Collections. Salt Lake City: Ancestry Publishing, 1986.

Yeary, Mamie. Reminiscences of the Boys in Gray, 1861–65. Dallas, TX: Wilkinson Printing Company, 1912.

Steven L. Warren

Overland Park, Kansas

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900

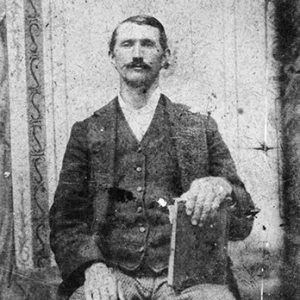

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age, 1875 through 1900 Edward Clanton

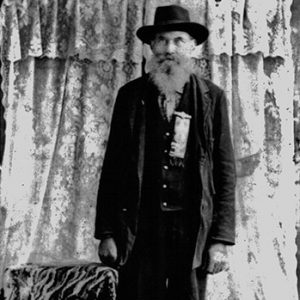

Edward Clanton  Wilbur Ridling

Wilbur Ridling

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.