calsfoundation@cals.org

Engagement at St. Charles

| Location: | Arkansas County |

| Campaign: | Pea Ridge Campaign |

| Date: | June 17, 1862 |

| Principal Commanders: | Colonel Graham N. Fitch, Commander Augustus H. Kilty (US); Captain Joseph Fry, Captain A. M. Williams (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | Forty-sixth Indiana and Union gunboats (US); Pleasant’s Twenty-ninth Arkansas Infantry, fifty men and the crews from the Confederate ships Maurepas and Pontchartrain (CS) |

| Estimated Casualties: | 160 (US); 6 killed, 1 wounded or missing in action (CS) |

| Result: | Union victory |

After the fall of Memphis, Tennessee, during the Civil War, the Confederate navy was on the defense. Three Confederate war ships made their way up Arkansas’s White River to save themselves and also to defend the White River from invasion by the Union troops.

Union major general Samuel R. Curtis and his Army of the Southwest advanced from Pea Ridge (Benton County) through the Ozark Mountains to Batesville (Independence County). Curtis later set up headquarters at Jacksonport (Jackson County), where the White and Black rivers converged.

Confederate major general Thomas C. Hindman, the “Lion of the South,” was in charge of the defense of Arkansas. Hindman’s main objective was to slow the Union side’s movement so that the Confederates could prepare to defend Arkansas. The main supply line to Jacksonport, Pocahontas (Randolph County), and Batesville was up the White and Black rivers. Curtis’s army hoped to use the White River as a way to receive supplies.

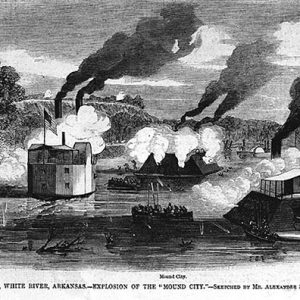

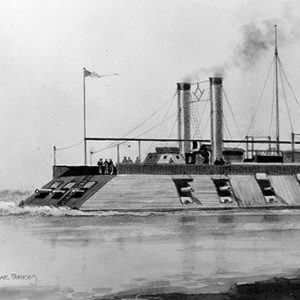

Captain Joseph Fry and Captain A. M. Williams picked the hamlet of St. Charles (Arkansas County) to set up two thirty-two-pounders, two three-inch rifled guns Lieutenant John W. Dunnington brought from the Little Rock Arsenal, a twelve-pounder howitzer and brass rifled cannon from the Maurepas, and two thirty-two pound guns to defend the White River. On the morning of June 17, 1862, four Federal ships—the ironclads Mound City and St. Louis and timberclads Lexington and Conestoga—traveled up the White for their rendezvous with Curtis and his men. Other smaller ships were also part of the Union flotilla.

Confederate captain Joseph Fry and Dunnington joined forces at St. Charles near DeWitt (Arkansas County). Pleasant’s Twenty-ninth Arkansas Infantry had thirty-five sharpshooters dispatched to assist in the defense of St. Charles. Also present were the crews of the two Confederate war ships, Maurepas and Pontchartrain. They laid plans to defend St. Charles with the resources they had. Fry sent out scouts and found that Union troops and gunboats outnumbered the Confederates. Fry ordered the Maurepas and the steamers Mary Patterson and Eliza G. scuttled to block the White River and then manned the guns in the earthworks at St. Charles.

When the Union ships rounded the bend, Fry opened fire. An early volley from the big guns sent a round that tore though the Mound City’s steam drum and filled the ship with scalding steam. This shot is called the “most deadly shot” of the war. The commander of the Mound City, Augustus H. Kilty, ordered the ship abandoned. About 175 sailors were aboard; 105 died, and forty-four were injured. (The Mound City did not sink but was towed to safety and repaired to fight another day.) Many drowned or were shot as they swam to shore. Only three officers and twenty-two soldiers escaped injury.

With the Mound City disabled, Union colonel Graham N. Fitch’s Forty-sixth Indiana Infantry was ordered off its ships just below St. Charles and marched upriver. A successful attack on the Confederate flank enabled Union troops to storm the batteries and occupy St. Charles. The skirmish lasted a short while, but the Union troops outnumbered the Confederates, and fearing capture, the Confederates yielded to greater numbers. Fry thought his troops could not hold St. Charles, so he ordered a retreat. Hindman reported six Confederates killed and one wounded.

The Union side set up a supply stop on the White River at St. Charles and left the wounded to be cared for by the citizens of the town. The Union gunboats, except for the Mound City, went upriver as far as Crooked Point Cutoff in Monroe County but had to turn back because the river was too low. The Union vessels could not supply Curtis at Batesville because the river was not deep enough for them to ascend beyond DeValls Bluff (Prairie County). Curtis’s forces had to live off the countryside while they marched south to reach their supplies. Despite having the “most deadly shot” of the war, this skirmish is not listed in most books on the Civil War. The sinking of the Confederate ships at St. Charles left the White River in control of the Union side for the remainder of the war.

A monument to the men who fell at St. Charles stands in the center of town.

For additional information:

Barnhart Jr., Donald. “The Deadliest Shot.” Civil War Times 45 (March/April 2006): 30–36.

Bearss, Edwin C. “The White River Expedition June 10–July 15, 1862.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 21 (Winter 1962): 305–362.

Christ, Mark K. “‘The Awful Scenes That Met My Eyes’: Union and Confederate Accounts of the Battle of St. Charles, June 17, 1862.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 71 (Winter 2012): 407–423.

Christ, Mark K. ed. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

Dickinson, Sam. “The Curse of St. Charles.” Arkansas Times, November 1984, pp. 100–106.

Evans, Clement A. Louisiana and Arkansas Confederate Military History. Vol. 10. Nashville, TN: Blue & Gray Press, 1899.

Ferguson, John L. “The Engagement at St. Charles in Its Historical Context.” Grand Prairie Historical Society Bulletin 5 (July 1962): 52–53.

Glenn, H. V. “The Battle of St. Charles.” Grand Prairie Historical Society Bulletin 4 (October 1961): 1–14.

———. “The Battle of St. Charles.” Grand Prairie Historical Society Bulletin 5 (January 1962): 1–11.

Henderson, J. M. Brief Stories of St. Charles in Romance & Tragedy. St. Charles, AR: St Charles Museum, n.d.

Johnson, Boyd W. “The Battle of St. Charles.” Grand Prairie Historical Society Bulletin 1 (July 1958): 8–12.

Spenser, Kay Terry. “History of St. Charles during the Civil War.” Grand Prairie Historical Society Bulletin 2 (January 1960): 29-32.

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Series 1, Vol. 13. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1890–1901.

W. Danny Honnoll

Jonesboro, Arkansas

Civil War Events Map

Civil War Events Map  Engagement at St. Charles

Engagement at St. Charles  Engagement at St. Charles

Engagement at St. Charles  Engagement at St. Charles Cannon

Engagement at St. Charles Cannon  Engagement at St. Charles Marker

Engagement at St. Charles Marker  Augustus Kilty

Augustus Kilty  Augustus Kilty

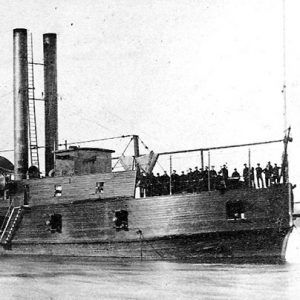

Augustus Kilty  USS Conestoga

USS Conestoga  USS Lexington

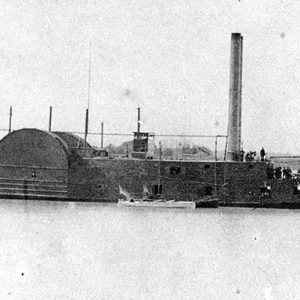

USS Lexington  USS Mound City

USS Mound City  USS St. Louis

USS St. Louis

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.