calsfoundation@cals.org

Memphis and Little Rock Railroad (M&LR)

The Memphis and Little Rock Railroad (M&LR) was the first railroad to operate in the state of Arkansas. The M&LR was a 133-mile-long railroad line that ran from Hopefield (Crittenden County), just opposite Memphis, Tennessee, to Little Rock (Pulaski County). A five-and-one-half-foot-gauge railroad, it was constructed between 1854 and 1871. At the beginning of the Civil War, only the eastern portion of the railroad between Hopefield and Madison (St. Francis County) was in operation. Construction on the eastern and western thirds of the railroad was complete in 1862, but the Civil War interrupted construction of the middle division of the railroad. During this period, the M&LR played a vital role for both Confederate and Union forces and was under Union control until 1865.

The M&LR was chartered by the State of Arkansas on January 10, 1853. It was estimated at that time that it would take $3.2 million to construct the line. Survey work commenced in 1854, and construction of the railroad was contracted to John H. Bradley & Company. The first rails were laid at Hopefield in 1856. The eastern, or first, division of the railroad terminated at Hopefield on the east and opposite Madison, on the St. Francis River, on the west. This first division was completed in November 1858.

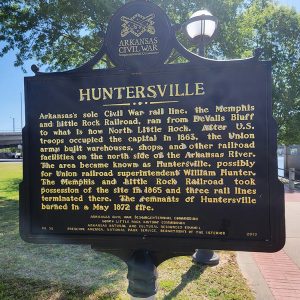

Construction work on the third division, or western division, began opposite Little Rock at Huntersville, now North Little Rock (Pulaski County), in 1861. After its completion to the White River at DeValls Bluff (Prairie County), it took between twenty-seven and thirty-six hours to travel between Memphis and Little Rock by combination of railroad, stagecoach, and steamboat—twenty-four hours shorter than by steamboat alone.

During the Civil War, the M&LR served as an important part of both Confederate and Union war efforts despite its middle section being incomplete. Prior to Federal occupation, the Confederate forces used the railroad’s machine shop at Hopefield to modernize rifles. The Confederates also frequently used the M&LR to transfer soldiers to Memphis. In June 1862, the shops and railroad fell under Federal control. Ultimately, the shops, depot, and engine shed were lost when Hopefield was burned by the Federal troops on February 19, 1863.

The western division of the railroad between Huntersville and DeValls Bluff proved to be an important strategic link during the Civil War. Union forces established a supply depot at DeValls Bluff. Steamboats brought supplies up the White River for shipment by the railroad to the supply depots at Huntersville and Little Rock. Because it was used to supply the Federal army, the western division was of vital importance to Major General Frederick Steele.

Frequent guerrilla attacks were made on the railroad, though none succeeded in keeping the railroad out of service for long. On July 6, 1864, Confederate skirmishers destroyed the tracks near Hick’s Stations, causing the train to derail, killing the fireman and injuring several others. About six weeks later, on August 24, Confederate brigadier general Joseph Shelby led 2,500 men in a successful attack against Union forces along the M&LR during the Skirmish at Ashley’s Station.

On November 1, 1865, the railroad was returned to control of the company. All the railroad facilities at Hopefield and much of the track had to be rebuilt, and the second, or middle, division was finally completed. Construction of this section proved costly because of the significant engineering obstacles in the lowlands between the Cache River and the L’Anguille River. During the Civil War, the railroad unsuccessfully sought funding from the Confederate government to close this gap. Under Federal military control, closing the gap was deemed too expensive and difficult. Ultimately, the $1.2 million to complete this section was given by the State of Arkansas in 1868. The drawbridge at DeValls Bluff was finished in 1871, and on April 11, 1871, the final spike was driven, completing the entire route of the M&LR. In 1872, a reporter for the New York Daily Tribune made the trip from Memphis to Little Rock and noted that it was necessary to “get a bottle of medicine for seasickness….It was the roughest road you ever saw in your life.” He noted that the train derailed twice before going forty miles and that it was a trip for the courageous and those with steady nerves.

The tracks along the eastern division and the middle division of the railroad were regularly inundated prior to the construction of the St. Francis River and Mississippi River levee systems. The problem was so prevalent that, in many places, the tracks were chained down or secured with wire rope to trees on the upstream side of the tracks. Frequently in the winter and spring, the railroad was inoperable between Hopefield and DeValls Bluff.

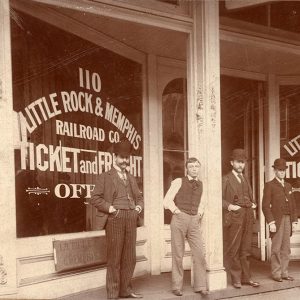

During the later half of the nineteenth century, the railroad was consistently in financial trouble and sold at foreclosure four times between 1873 and 1898. The first M&LR was sold to the Memphis and Little Rock Railway Company in December 1873. It was again sold to a second Memphis and Little Rock Railroad Company in 1877. Then in 1887, it was sold to the Little Rock and Memphis Railroad Company. In April 1897, the Mississippi River washed out forty miles of track on the eastern division of the railroad.

Though operations continued via the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railroad, the cost of rebuilding was simply too great a burden, and the railroad was sold at foreclosure on October 25, 1898, to the Choctaw and Memphis Railroad Company for only $325,000. The Choctaw and Memphis was in turn sold to the Choctaw, Oklahoma, and Gulf Railroad Company—nicknamed the Choctaw Route—in 1900. The Choctaw Route was later purchased by the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railway Company.

For additional information:

Fair, James R. “Hopefield, Arkansas: Important River-Rail Terminal.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 57 (Summer 1998): 191–204.

Hayes, William Edward. Iron Road to Empire: The History of 100 Years of Progress on the Rock Island Lines. Newton, IA: CPM LLC, 2000.

Huff, Leo E. “The Memphis and Little Rock Railroad during the Civil War.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 23 (Autumn 1964): 260–270.

Nelson, John H., ed. 1922 Rock Island Magazine Reprint. Newton, IA: CPM LLC, 2000.

Porter, Scott A. “Thunder across the Arkansas Prairie: Shelby’s Opening Salvo in the 1864 Invasion of Missouri.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Spring 2007): 43–56.

Sayger, Bill. “The End of the Line.” Arkansas Times, July 1985, pp. 44–49, 69.

Wood, Stephen E. “The Development of Arkansas Railroads.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 7 (Summer 1948): 103–118.

———. “The Development of Arkansas Railroads.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 7 (Autumn 1948): 155–193.

Van Zbinden

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

Little Rock Fortifications (Civil War)

Little Rock Fortifications (Civil War) Transportation

Transportation Huntersville Sign

Huntersville Sign  Hunterville

Hunterville  Railroad Ticket Office

Railroad Ticket Office

I think I have a few of this company’s original stock certificates. Navy yard bonds. $1,000 bonds and their coupon pages. That along with a few envelopes from the Southern Express Company that delivered payments to people affiliated with the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad Company. I keep seeing the same name Ester, Elliott, and elder. Dated 1857. Even a handwritten letter written inside one of the envelopes. John Robinson or Robertson. President.