calsfoundation@cals.org

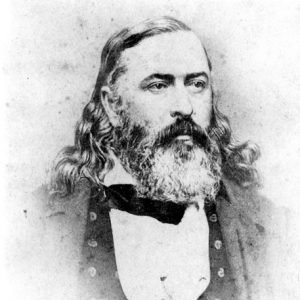

Albert Pike (1809–1891)

Albert Pike was a lawyer who played a major role in the development of the early courts of Arkansas and played an active role in the state’s politics prior to the Civil War. He also was a central figure in the development of Masonry in the state and later became a national leader of that organization. During the Civil War, he commanded the Confederacy’s Indian Territory, raising troops there and exercising field command in one battle. He also was a talented poet and writer.

Albert Pike was born in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 29, 1809. He was one of the six children of Benjamin Pike, a cobbler, and Sarah Andrews. He attended public schools in Byfield, Newburyport, and Framingham, Massachusetts. He received an education that provided him with a background in classical and contemporary literature and in Hebrew, Latin, and Greek. He passed the examination required for entry into Harvard when he was sixteen. He was unable to pay the tuition at Harvard, however, and began to teach, working at schools in Newburyport and nearby Gloucester and Fairhaven. Later in his life, in 1859, he earned an honorary Master of Arts degree from Harvard “for his deep scholarship.”

He began to write poetry as a young man, which he continued to do for the rest of his life. When he was twenty-three, he published his first poem, “Hymns to the Gods.” Subsequent poems appeared in contemporary literary journals such as Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine and local newspapers. His first collection of poetry, Prose Sketches and Poems Written in the Western Country, appeared in 1834. He later gathered many of his poems and republished them in Hymns to the Gods and Other Poems (1872). After his death these appeared again in Gen. Albert Pike’s Poems (1900) and Lyrics and Love Songs (1916).

Pike left Massachusetts for Santa Fe, in what was then Mexico, in 1831, one of many at the time attracted to the developing West. From Santa Fe, he joined in an expedition into the lands around the headwaters of the Arkansas and Red rivers. Somewhere along the route, he left the expedition and walked to Fort Smith (Sebastian County). He taught there in rural schools for a short time, but his literary skills early involved him in Arkansas politics. In 1833, he published in local newspapers letters in support of Robert Crittenden’s candidacy for territorial delegate to Congress. The anonymous letters, signed “Casca” after one of the Roman politicians who assassinated Julius Caesar, were considered very persuasive and secured for him a statewide reputation as a writer. They also attracted the attention of Charles Bertrand, owner of the Whig Party’s Arkansas Advocate, who invited Pike to Little Rock (Pulaski County) to work as the paper’s editor. Pike accepted the job and moved to the capital city. While working for the Advocate, Pike published a series of stories and poems about his adventures in New Mexico, the material later published in his Prose Stories and Poems Written in the Western Country.

In addition to editing the newspaper, Pike secured additional work in Little Rock as a clerk in the legislature. He married Mary Ann Hamilton on October 10, 1834. The couple had six children. Hamilton brought to the marriage considerable financial resources, and she helped Pike purchase an interest in the Advocate from Bertrand in 1834. The next year, he became its sole proprietor. Pike studied law while editing the newspaper, ultimately passing the Arkansas Bar exam in either 1836 or 1837. In the latter year, he sold the newspaper and devoted his time to the law. He demonstrated considerable legal prowess early and represented clients in courts at every level, including the United States Supreme Court, which he received permission to practice before in 1849.

Pike developed a lucrative law practice, and his clients included many of the tribes in Indian Territory. Among his clients at this time were the Creek (Muscogee) and Choctaw, whom he represented in a case against the U.S. government that secured payment for lands taken in the Treaty of Fort Jackson in 1814. Pike learned several Native American dialects while working as their attorney.

From 1836 to 1844, Pike was the first reporter of the Arkansas Supreme Court, charged with writing notes on the relevant points in court decisions, then publishing and indexing the court’s opinions. In 1842, he published the Arkansas Form Book, a tool for lawyers providing models for the different kinds of motions to be filed in the state’s courts. His reputation as an attorney also secured him the appointment of receiver for the failed Arkansas State Bank in 1840. As receiver, he attempted to collect the debts owed to that institution. At the same time, the fees he received for this work were lucrative and secured his fortune.

An ambitious public figure, Pike joined others in 1845 in supporting actions against Mexico, what became the Mexican War. He helped raise the Little Rock Guards, a company incorporated into the Arkansas cavalry regiment of Colonel Archibald Yell, and served as its captain. Pike concluded early on that the senior officers of his regiment were incompetent, and he shared his observations with the people back in Arkansas through letters to the newspapers. Following the Battle of Buena Vista, he leveled particularly harsh criticism against Lieutenant Colonel John Selden Roane. After the publication of a particularly vitriolic letter by Pike in the Arkansas Gazette, Roane demanded that Pike apologize or “give him satisfaction.” Pike refused to apologize, and the two fought a duel near Fort Smith on a sand bank in the Arkansas River. In the exchange of fire, neither hit his antagonist, and the two were persuaded to halt the duel, with honor satisfied.

Returning from Mexico, Pike reestablished his law practice. He promoted the construction of a transcontinental railroad from New Orleans to the Pacific coast, writing numerous newspaper essays urging support for this project. He moved to New Orleans in 1853 to further his railroad activities, although he also continued to practice law. He translated French legal volumes into English while preparing to pass the local bar exam for Louisiana. Ultimately, he successfully obtained a charter from the Louisiana legislature for one of his railroad projects. He returned to Little Rock in 1857.

In the years immediately following the Mexican War, Pike’s concern with the developing sectional crisis brought on by the issue of slavery became apparent. He had long been a Whig, but the Whig Party repeatedly refused to address the slavery issue. That failure and Pike’s own anti-Catholicism led him to join the Know-Nothing Party upon its creation. In 1856, he attended the new party’s national convention, but he found it equally reluctant to adopt a strong pro-slavery platform. He joined other Southern delegates in walking out of the convention. Pike expressed a belief in states’ rights and considered secession constitutional. He philosophically supported secession, demonstrating his position in 1861 when he published a pamphlet titled State or Province, Bond or Free?

In 1861, the Arkansas state secession convention named Pike its commissioner to Indian Territory and authorized him to negotiate treaties with the various tribes. As a result of his experience there, the Confederate War Department appointed him a brigadier general in the Confederate army in August 1861 and assigned him to the Department of the Indian Territory. Pike assisted the tribes that supported the Confederacy in raising regiments. He believed that these units would be critical to protecting the territory from Union incursions, but his belief that the Indian units should be kept in Indian Territory brought him into early conflict with his superiors. In the spring of 1862, General Earl Van Dorn ordered him to bring his 2,500 Indian troops into northwestern Arkansas. Despite his opposition to the move, Pike obeyed, and his Indian force of about 900 men joined Confederate forces in northwest Arkansas. On March 7–8, 1862, they participated in the Battle of Pea Ridge (a.k.a. Elkhorn Tavern), led by Pike. Pike proved a poor leader, and he failed to keep his force engaged with the enemy or in check. Charges circulated widely that the men had stopped their advance to take scalps. After the battle, Pike and his men returned to Indian Territory.

Opposition to Confederate policy over Indian Territory would continue to be a source of conflict between Pike and his superiors. Unhappy with Pike, in the summer of 1862, General Thomas C. Hindman, commander of Confederate forces in Arkansas, attempted to extend his authority over the territory. Pike responded by issuing a circular that refused to surrender control and charged Hindman with trying to replace constitutional government with despotism. Ultimately, the dispute between the two went to Confederate authorities at Richmond. The authorities decided in favor of Hindman and reprimanded Pike. On July 12, Pike resigned from his position in protest. With his resignation, Pike retired to Greasy Cove in Montgomery County. He was appointed as a judge of the state Supreme Court in 1864, but little is known of his activities on the court.

At the end of the Civil War, Pike moved to New York City, then for a short time to Canada. After receiving an amnesty from President Andrew Johnson on August 30, 1865, he returned for a time to Arkansas and resumed the practice of law. In 1867, he moved to Memphis, Tennessee, and entered a new law partnership with General Charles W. Adams. He also edited the Memphis Appeal. He may have become involved in the organization of the Ku Klux Klan at this time, although this is not certain. He moved to Washington DC in 1870. There, he engaged for a time in politics, editing The Patriot, a Democratic newspaper, from 1868 to 1870. He also practiced law in partnership with Robert W. Johnson, former U.S. senator, until 1880. Although less interested in Arkansas affairs, one of his last major roles in the state would be his support to the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant of Elisha Baxter’s claims for the governorship in 1874.

After he ceased practicing law, Pike’s real interest was the Masonic Lodge. He had become a Mason in 1850 and participated in the creation of the Masonic St. Johns’ College in Little Rock that same year. In 1851, he helped to form the Grand Chapter of Arkansas and was its Grand High Priest from 1853 to 1854. In 1853, he also associated with the Scottish Rite of Masons and rose rapidly in the organization. In 1859, he was elected grand commander of the Supreme Council, Southern Jurisdiction of the United States, the administrative district for all parts of the country except for the fifteen states east of the Mississippi River and north of the Ohio, and held that post until his death. After the war, he devoted much of his time to rewriting the rituals of the Scottish Rite Masons. For years, his Morals and Dogma (1871), still in print, was distributed to members of the Rite. Over his career, he published numerous other works on the order, including Meaning of Masonry, Book of the Words, and The Point Within the Circle. As he aged, he also became interested in spiritualism, particularly Indian thought, and its relationship to Masonry. Late in life, he learned Sanskrit and translated various literary works written in that language. As a result of his work in this area, he published Indo-Aryan Deities and Worship as Contained in the Rig-Veda.

Pike died at the Scottish Rite Temple in Washington DC on April 2, 1891. He was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery there. On December 29, 1944, the anniversary of his birth, his body was removed from Oak Hill Cemetery and placed in a crypt in the temple.

Pike was much honored after his death. His Masonic brothers erected a statute to him in 1901 in Washington DC. Authorities also named the first highway between Hot Springs (Garland County) and Colorado Springs, Colorado, the Albert Pike Highway. The Albert Pike Hotel bears his name, as does the Albert Pike Memorial Temple, both in Little Rock, and his Little Rock home remains standing.

Discussions about removing the statue in Washington DC (and other statues of Confederates around the country) began in the summer of 2017, following a white supremacist rally at Confederate monuments in Charlottesville, Virginia. On June 19, 2020, the statue was toppled amid ongoing protests across the nation following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota. On August 4, 2025, the National Park Service announced that the statue was being restored for reinstallation. It was reinstalled on October 25, 2025, despite a shutdown of the federal government at the time.

For additional information:

Albert Pike Letters and Documents. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Allsopp, Frederick William. Albert Pike: A Biography. Little Rock: Parke-Harper, 1928.

Baker, Virgil L. “Albert Pike: Citizen Speechmaker of Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 10 (Summer 1951): 138–156.

Brown, Walter L. A Life of Albert Pike. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Bullock, Steven C. Revolutionary Brotherhood: Freemasonry and the Transformation of the American Social Order, 1730–1840. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Cioffi, Chris. “Toppled, Warehoused, Waiting: Confederate Statue Still in Limbo in D.C.” Roll Call, November 18, 2020. https://rollcall.com/2020/11/18/locked-in-storage-confederate-statue-albert-pike/ (accessed June 30, 2022).

Duncan, Robert Lipscomb. Reluctant General: The Life and Times of Albert Pike. New York: Dutton, 1961.

Jones, Alexander E. “Albert Pike as a Tenderfoot.” New Mexico Historical Review 31.2 (1956): 140–147.

Keller, Mark, and Thomas A. Besler Jr. “Albert Pike’s Contributions to the Spirit of the Times, Including His ‘Letter from the Far, Far West’.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (Winter 1978): 318–353.

Portnoy, Jenna. “A Homeless Confederate? Albert Pike’s Complicated Legacy Leaves Statue in Limbo.” Washington Post, October 30, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/dc-politics/a-homeless-confederate-albert-pikes-complicated-legacy-leaves-statue-in-limbo/2017/10/16/40fe05d6-aa10-11e7-92d1-58c702d2d975_story.html (accessed June 30, 2022).

Riley, Susan. “Albert Pike as an American Don Juan.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 19 (Autumn 1960): 207–224.

Shepherd, William. The Seven Honor Men of Arkansas Scottish Rite Masonry. Conway, AR: River Road Press, 1978.

Uzzel, Robert Lesley. “The Kabbalistic Thought of Eliphas Levi and Its Influence in America.” PhD diss., Baylor University, 1995.

Carl H. Moneyhon

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Albert Pike was a Confederate in the Civil War. With the number of re-enactments of that war, it is obvious that Confederates’ descendants are proud of their ancestors’ participation, just as African Americans are proud that the Union won. We want our children to know who these buildings, counties, and other monuments are edifying–Albert Pike, a Confederate who fought on the side of slavery.

For a year or two, Albert Pike disappeared into southern Arkansas, perhaps to Greasy Cove, in the Ouachita Mountains some eighteen miles west of Caddo Gap. Beyond legends, what proof places Pike at Greasy Cove? Local lore and printed sources suggest he was an early incognito area landowner who took up temporary residence when needed, bringing with him slaves, furniture, a sizable library, a personal fortune, and the desire to be left alone. Pike resigned his Confederate commission in July 1862. Sought by both sides forces, he temporarily avoided detection in Arkansas. Did Pike really live at Greasy Cove? Some critics say absolutely not. But his wartime presence in the general area was later confirmed. Local folk conjectured that he gathered books and papers from the Pike County location used to secure them after his June 1862 Little Rock departure. Then, in 1864, he made his way to Greasy Cove. He became absorbed in research and writing and lived a reclusive existence, except for occasional visits from local Masons. One Masonic publication said this time might be called an apocryphal period of his life. Pike remained at Greasy Cove, according to this highly valued tradition, until rumors of his supposed wealth, a trunk of gold, lured a band of jayhawkers to his cabin. These lawless guerrillas were said to have destroyed furniture, thrown Pikes books onto the yard or into the river, and threatened him for the gold. Another version has Pike escaping under the cover of darkness with a few personal possessions and an early manuscript of his Masonic Morals and Dogma, swimming the Little Missouri River to safety. Having been discovered, Albert Pikethe Legend of Greasy Coveleft shortly after this episode, never to return.