Elaine Nurses

Elaine Nurses

Entry Category: Civil Rights and Social Change

Elaine Nurses

Elaine Nurses

Elligin and Anderson (Lynching of)

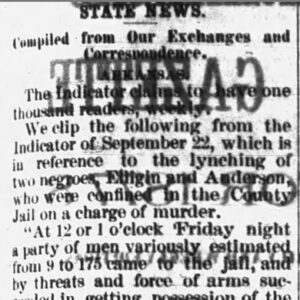

Elligin and Anderson Lynching Article

Elligin and Anderson Lynching Article

Ellington, Alice Sankey

Ellison and Son

Ellison and Son

Ellison, Clyde (Lynching of)

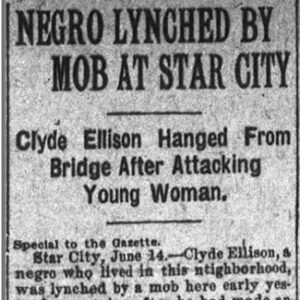

Ellison Lynching Article

Ellison Lynching Article

Ellison, Eugene (Killing of)

Emancipation

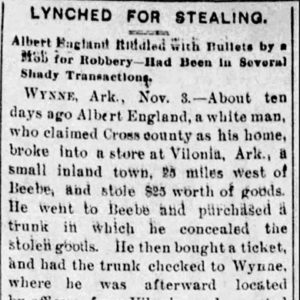

England Lynching Editorial

England Lynching Editorial

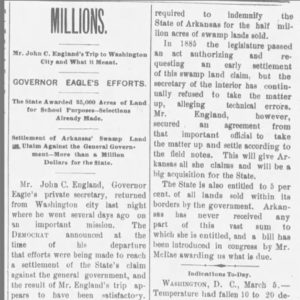

John England Article

John England Article

Environmental Racism

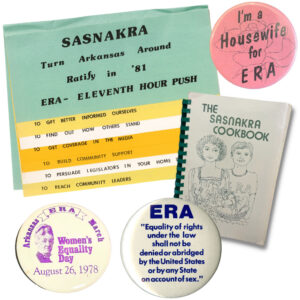

Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)

ERA Ephemera

ERA Ephemera

Eugene Ellison

Eugene Ellison

Factory System

aka: Indian Trading Posts

aka: Indian Factory System

Farmer, John (Lynching of)

Fayetteville Female Seminary

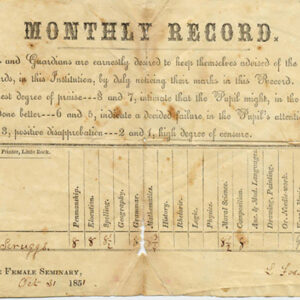

Fayetteville Female Seminary Report Card

Fayetteville Female Seminary Report Card

Fayetteville Schools, Desegregation of

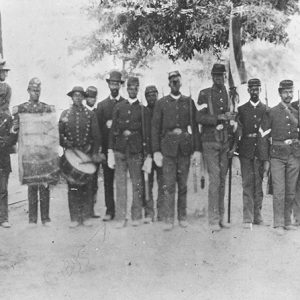

Fifty-seventh U.S. Colored Infantry

Fifty-seventh U.S. Colored Infantry

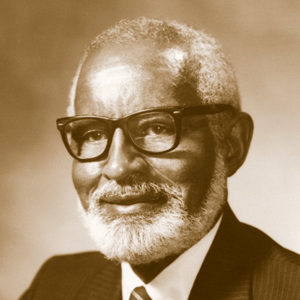

Jacob Fink

Jacob Fink

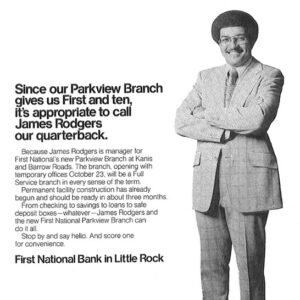

First National Bank Ad

First National Bank Ad

Fleming, Sam (Lynching of)

Flemming, Owen (Lynching of)

Adolphine Krause Fletcher

Adolphine Krause Fletcher

Flowers, Beulah Lee Sampson

William Harold Flowers

William Harold Flowers

Flowers, William Harold

James Ford

James Ford

Forrest City Riot of 1889

Fort Smith Schools, Desegregation of

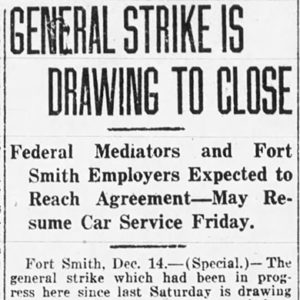

Fort Smith Strike Article

Fort Smith Strike Article

Fort Smith Telephone Operators Strike of 1917

Foster, Thomas P. (Killing of)

Fox, Joseph (Joe)

Fox, Warren (Lynching of)

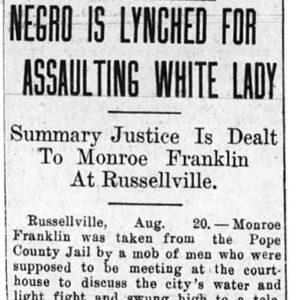

Franklin, Monroe (Lynching of)

Monroe Franklin Lynching Article

Monroe Franklin Lynching Article

Frederick, Bart (Lynchings Related to the Murder of)

Freedmen’s Bureau

aka: Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands

Freedmen’s Schools

Freedom Centers, Houses, Schools, and Libraries

Freedom Rides

Furbush, William Hines

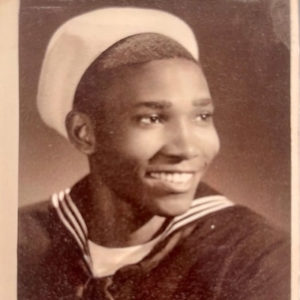

Fussell, Robert Foreman (Bobby)

Fyler, Eliza A. (Lizzie) Dorman

Gammon, John, Jr.

Garden Party

Garden Party