calsfoundation@cals.org

Red River

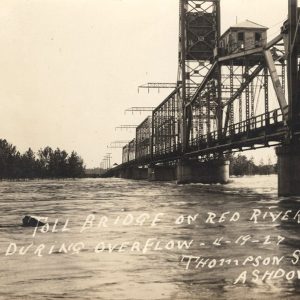

The Red River emerges from two forks in the Texas panhandle and flows east approximately 1,290 miles, forming the border between Oklahoma and Texas as well as part of the border between Texas and Arkansas. In southwestern Arkansas near Fulton (Hempstead County), the Red River takes a decidedly southern turn before entering Louisiana, where it flows southeasterly before emptying into the Mississippi River northeast of the town of Simmesport. Although only approximately 180 miles of the Red River touches upon or passes through the state of Arkansas, it has had a major impact upon the people of southwestern Arkansas from prehistoric times to the present day.

Important prehistoric Caddo artifacts have been unearthed in the Red River valley, particularly the Crenshaw and Bowman sites in Arkansas and the Mounds Plantation Site in Louisiana, and the Caddo established a number of prehistoric salt works along the tributaries of the Red River in Arkansas. Caddoan mound-building survived along the Red River valley, though with stylistic differences, even as it disappeared within other river valleys during the late Mississippian Period. There is archaeological evidence for a dense population of people along the Red River from the “Great Bend” near Fulton south to Shreveport. Luís de Moscoso, leader of the Hernando de Soto expedition after de Soto’s death, crossed the Red River in 1542. Not until 1687 did European explorers again visit the river, this time the French, who established trading posts along the river, most notably at present-day Natchitoches, Louisiana. The Kadohadacho Caddo continued to live along the river in the vicinity of Texarkana (Miller County) until 1790, when they moved downstream into Louisiana. They sold their land along the Red River to the United States government effective July 1, 1835, at which time they moved into Mexico; but due to war between the United States and Mexico, they ended up living in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). The Freeman and Custis Expedition, which set forth in search of the headwaters of the Red River in 1806, made use of Caddo guides whom they encountered in the vicinity of the present Arkansas–Louisiana border.

Until the late nineteenth century, the Red River’s utility as a transportation corridor between the Mississippi River and points west of present-day Shreveport was impeded by the Great Raft, or Red River Raft, an enormous logjam that clogged the lower part of the river, extending to more than 130 miles at one point. The raft likely existed for hundreds of years; it was so old that, according to some sources, it actually became a part of Caddo mythology. In 1828, the U.S. Congress set aside $25,000 for the raft’s removal, and Captain Henry Miller Shreve, then serving as the Superintendent of Western River Improvement, was assigned the task of clearing the raft in 1832. In 1838, he completed the task, though it re-formed farther up the river soon thereafter and eventually extended to the Arkansas border. Congress hesitated in setting aside more money for the clearance project, with many members feeling it to be a lost cause.

During the Civil War, the Red River Campaign of 1864 entailed Union incursions into southwest Arkansas and northwest Louisiana along the Red River, with the greater goal of pushing into Texas. General-in-Chief Henry Halleck and Major General William T. Sherman both believed the Red River to be “the shortest and best line of defense for Louisiana and Arkansas,” overruling General Nathaniel Prentiss Banks, who argued that the river was too dangerous to be used as a route for invasion. During the push into Confederate territory, an unseasonal lack of rain left the Red lower than usual, which exposed snags and sandbars that hampered the progress of Union gunboats on the river in Louisiana. In the end, the Confederates were able to repel this ill-conceived invasion.

In 1873, the second Red River raft was finally removed under the direction of Lieutenant Eugene Woodruff. Dams were placed along bayous emptying into river to prevent any raft from re-forming. Despite the eventual clearing of the river, however, no major towns in Arkansas were established upon the Red, though Texarkana, Hope (Hempstead County), and Lewisville (Lafayette County) all lie at a few miles’ remove. Until 1900, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers straightened the channel of the river, with the result that steamboat traffic increased as boats were able to transport goods from the mouth of the Mississippi River through Arkansas and into Texas and Oklahoma and back again; for the whole of the year, the river was navigable to Garland (Miller County), where the St. Louis, Arkansas, and Texas Railway (Cotton Belt Route) crossed the river. This railroad, as well as the St. Louis, Iron Mountain and Southern Railway, which crossed the Red River at Fulton, provided stiff competition for steamboats, soon replacing them entirely.

Though the U.S. Congress had, since 1927, put forward money for studying the potential for improving the nation’s rivers with an eye toward navigation and flood control, not until the Flood Act of 1938 did Congress authorize the Corps of Engineers to construct a dam on the Red River at Denison, Texas. After the Flood Control Act of 1946, the Corps of Engineers began a fairly constant spate of work on the river, including a variety of canals and locks and dams. In 1978, representatives of Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana signed the Red River Compact, which provides an apportionment of the waters of the river to the four signatories as well as a means for conserving and protecting it.

For additional information:

Cole-Jett, Robin. The Red River Valley in Arkansas. Charleston: SC: The History Press, 2014.

Flores, Dan L., ed. Southern Counterpart to Lewis and Clark: The Freeman and Custis Expedition of 1806. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002.

Joiner, Gary. Through the Howling Wilderness: The 1864 Red River Campaign and Union Failure in the West. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2006.

Tyson, Carl Newton. The Red River in Southwestern History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1981.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.