calsfoundation@cals.org

Planarians

aka: Triclads

There are at least seven species of planarians found in Arkansas, on land and in water. Planarians belong to the superphylum Lophotrochozoa, phylum Platyhelminthes, subphylum Catenulidea, class Rhabditophora (some consider the artificial grouping Turbellaria), order Tricladida, suborder Paludicola, and families Dugesiidae, Kenkiidae, Planariidae, and Dendrocoelidae. These flatworms are often simply referred to as triclads or triclad worms. Currently, the order Tricladida is split into three suborders, including the marine forms (Maricola); those found mostly in freshwater habitats of caves, although at least one species occurs in surface waters (Cavernicola); and land planarians/freshwater triclads (Continenticola). Scientists have argued about the systematics of platyhelminths for many years, and with the advent of molecular approaches (18S and 28S ribosomal DNA sequences), older classification schemes are being reconsidered, particularly among “turbellarians.” Indeed, not all taxonomists agree upon any one classification or the phylogenetic relationships among the various taxa.

One of the most famous biologists to study planarians was Libbie Henrietta Hyman (1888‒1969). She published her first group of papers on planarians while at the University of Chicago, and many more were published during her career. Another biologist, Roman Kenk (1898–1988) of the Smithsonian Institution, also provided a great deal of taxonomic information on North American planarians. He described more than thirty Nearctic species, and a Nearctic family (Kenkiidae) and genus (Kenkia) of planarians were named in his honor.

Ecologically, planarians are flatworms with mostly a free-living mode of life to include marine and freshwater species, as well as some terrestrial forms. Marine planarian species dwell on the bottom of tidal or subtidal zones of the ocean. Aquatic and semi-aquatic forms frequent streams and spring pools, while others are found in flowing mountain streams. Terrestrial species are found in moist habitats under stones, logs, and stems of aquatic plants mostly in the tropics and subtropics. There are about seventy-five species of freshwater planarians in North America and six species of terrestrial forms in the United States. An older study published in 1979 reported seven species of planarians from Arkansas, but there is no more recent report, and the total number is probably greater.

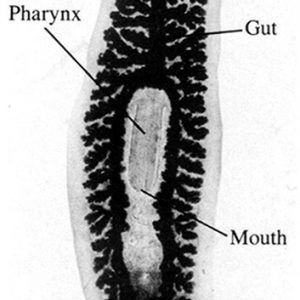

Planarians are unsegmented, primarily bilaterally symmetrical, usually dorsoventrally flattened worms; they are rarely parasitic—most are free-living. They range in size from about 5 to 500 mm (0.2 to 19.7 in.). All are triploblastic with three well-defined germ layers (endodermal, mesodermal, and ectodermal), although they do not have a coelom (acoelomate). Their gut region may be simple or complex and triply-branched with numerous diverticula—it basically is a blind sac. Planarians show cephalization (concentration of sensory organs in the head) and have a primitive central nervous system (CNS) composed of a pair of anterior cerebral ganglia and usually longitudinal nerve cords connected by transverse commissures; these are located within the mesenchyme in most species. This type of CNS is called a ladder-type (orthogon) nervous system because of its structure. Some common planarians like Dugesia (Girardia) spp. have sensory lobes (auricles) for sensation and perception that make the head region appear triangular, and two eyespots (ocelli) are also found on the head. Planarians are the simplest animals with an excretory system by having protonephridia or flame cells as their excretory/osmoregulatory structures. A few planarians have a syncytial epidermis with nuclei not separated from each other by intervening cell membranes. The epidermis contains rod-like cells called rhabdites that swell and form a protective sheath of mucus. Also, adhesive and releaser glands are present on the epithelial surface that produce a chemical that attaches the individual to a substrate, and that secrete a chemical that dissolves the attachment when needed, respectively.

In terms of reproduction, planarians have a rather complex system, with both male and female organs opening through a common genital aperture (pore) mostly on the ventral surface. They have well-developed gonads, ducts, and accessory organs. Most planarians are hermaphroditic (monoecious) and reproduce by fission, but cross fertilization (sexual reproduction) is possible between two specimens. Freshwater planarians can reproduce asexually simply by constricting behind the pharynx and separating in two individuals (zooids), each of which can regenerate missing portions. After copulation, one or more fertilized eggs and some yolk cells become enclosed within a small cocoon (hard capsule) that is attached by little stalks to the underside of rocks or plants. In some species, the yolk for nutrition in the developing embryo is endolecithal (contained within the egg cell itself)—an ancestral condition for flatworms. The development of the embryo is via spiral determinate cleavage. Emerging embryos are already juveniles that resemble larger mature adults. Some marine forms possess embryos that develop into a ciliated free-swimming larva.

Planarians have the ability to regenerate tissue completely from small body fragments, a biological process requiring a population of neoblasts (proliferating cells). Planarians have been used as a model organism in biology laboratories for many years, given that students can “create lives” by cutting a flatworm in half and watching how each part regenerates its missing parts, thereby producing two new individuals.

Planarians are predatory carnivorous specialists when feeding. Examples include those that prey on ascidians, bryozoans, crustaceans, nematodes, rotifers, and even insects (midge larvae). They detect food items by chemoreception and capture prey in their mucus secretions. Any given planarian can grip its prey with its anterior end, wrap its body around the item, extend its proboscis, and suck up the food. Predators of planarians include freshwater fishes, amphibians, and aquatic insect larvae (dragonflies and damselflies, chironomids, and mosquitoes).

In Arkansas, there are both terrestrial and freshwater planarians. To date, only two land planarians have been reported from Arkansas. A single specimen of Microplana atrocyaneus was collected at Stair (Marion County) in 1942, while Bipalium kewense was first reported in 1976. Land planarians in the state are generally long (up to 170 mm [6.7 in.]), slender flatworms found in moist, dark habitats such as under boards, concrete slabs, and logs, and in leaf mold. These organisms are thought to be among the most primitive metazoans that can live successfully in a terrestrial environment. However, they require high humidity since prolonged exposure to air presents a danger of dehydration. Planarians secrete a protective mucus slime coat that prevents dehydration and can be seen as a slime trail marking the flatworm’s previous route on land.

The greatest abundance of land planarians is found in damp rainforests in the tropics and subtropics where the most abundant numbers and greatest diversity of species occur. In temperate areas such as Europe and North America, land planarians are less abundant due to the lack of high humidity. Native land planarians are usually relatively small (12 mm [0.5 in.]) in the midwestern and eastern United States and include the following: M. atrocyaneus, M. rufocephalata, Rhyncodemus sylvaticus, R. americanus, and Diporodemus indigenous. In addition, several exotic species of land planarians have been introduced into the United States from the tropics, including Dolichoplana striata, Geoplana mexicana, G. vaga, B. adventitium, and B. kewense. These planarians are believed to have been introduced by way of imported plants, and in many cases they have been discovered in or near greenhouses. One of the most ubiquitous of these exotics is B. kewense, and it seems to be well established outdoors in the mid-South and the southeastern United States in several states, including Alabama, Arkansas, California, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, New Jersey, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee, as well as Washington DC.

Bipalium kewense is a large, conspicuous flatworm reaching up to 17 cm or more in length, with a pronounced lunate or spade-like head. It is brightly marked with five dark brown stripes running the length of the body on a light brown or olivaceous background. Bipalium kewense cannot survive submersion in water. In addition, collection of a possible third land planarian believed it to be Geoplana vaga was made in Arkansas. However, upon further microscopic examination of the genitalia of this 6.5 cm (2.6 in.) specimen, it did not match the description of G. plana, suggesting it might have been an undescribed species. To date, the exact identity of this specimen has not been resolved.

The most well-known planarian in Arkansas is the invasive B. kewense, which has been found a number of times in Arkansas, primarily in greenhouse situations or private residences. Bipalium kewense is easily identified by its diagnostic spade-like head and bi-colored body. It is known from Ashley, Chicot, Clark, Columbia, Dallas, Faulkner, Jefferson, Miller, Ouachita, Polk, Pope, Pulaski, and Union counties. Although native to tropical Asia, land planarians have been dispersed via the trade in tropical plants; thus they commonly are observed in greenhouses in the soil of potted plants and have become established across the southern United States. They are often found after heavy rains on driveways or sidewalks, although specimens have been discovered under wet boards, logs, rotting trees, railroad ties, and concrete patio slabs. The establishment of B. kewense is of concern because it can be detrimental to populations of earthworms, on which they feed by apparently using a neurotoxin (tetrodotoxin) for paralysis.

Freshwater planarians occur throughout Arkansas in favorable habitat and include the following: Cura foremanii from streams in the Interior Highlands and Gulf Coastal Plain; Dendrocoelopsis americana from Logan, Polk, and Washington counties; D. dorotocephala from seventeen counties; Girardia tigrina, the most common Arkansas planarian, which occurs in at least twenty-three counties; an immature Phagocata sp. from Cleburne, Izard, and Lawrence counties; P. gracilis from five counties; and Proctyla fluviatilis from Crittenden County. They prefer springs, seeps, caves, and other fishless areas. Interestingly, while several flatworms have been found in Arkansas caves, only a single species, D. americana, may be considered a cave obligate (troglobitic) species. It is considered critically imperiled (S1) in Arkansas and also occurs in Missouri and Oklahoma caves. In addition, a number of populations of D. americana are forms possessing eyes, but an eyeless population was reported from a well in Texas. An unidentified cave triclad flatworm from a cave in the Sylamore Ranger District and in three caves in the Buffalo National River, and P. gracilis from Rowland Cave (Stone County), were reported in Arkansas but, to date, the former had not yet been identified. Reports of cave flatworms are not well known from the state but may simply reflect minimal collecting effort rather than the lack of species.

For additional information:

Álvarez-Presas, M., J. Baguñà, and M. Riutort. “Molecular Phylogeny of Land and Freshwater Planarians (Tricladida, Platyhelminthes): From Freshwater to Land and Back.” Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 47 (2008): 555–568.

Brusca, R. C., W. Moore, and S. M. Schuster. Invertebrates. 3rd ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates Inc., 2018.

Darlington, Julian, and C. Chandler. “A Survey of the Planarians (Tricladida: Paludicola) of Arkansas.” Southwestern Naturalist 24 (1979): 141‒148.

Dickens, J. C., A. N. Stokes, P. K. Ducey, Lorie Neuman-Lee, C. T. Hanifin, S. S. French, M. E. Pfrender, Edmund D. Brodie, and Edmund D. Brodie Jr. “Confirmation and Distribution of Tetrodotoxin for the First Time in Terrestrial Invertebrates: Two Terrestrial Flatworm Species (Bipalium adventitium and Bipalium kewense).” PLoS ONE 9 (2014): e100718.

Dindal, D. L. “Feeding Behavior of a Terrestrial Turbellarian Bipalium adventitium.” American Midland Naturalist 83 (1970): 635‒637.

Dundee, D. S., and H. A. Dundee. “Observations on the Land Planarian Bipalium kewense Mosely in the Gulf Coast.” Systematic Zoology 12 (1963): 36‒37.

Ducey, P. K., M. McCormick, and E. Davidson. “Natural History Observations on Bipalium cf. vagum Jones and Sterrer (Platyhelminthes: Tricladida), a Terrestrial Broadhead Planarian New to North America.” Southeastern Naturalist 6 (2007): 449‒460.

Ducey, P. K., M. Messere, K. Lapoint, and S. Noce. “Lumbricid Prey and Potential Herpetofaunal Predators of the Invading Terrestrial Flatworm Bipalium adventitium (Turbellaria: Tricladida: Terricola).” American Midland Naturalist 141 (1999): 305‒314.

Graening, G. O., Danté B. Fenolio, and Michael E. Slay. Cave Life of Oklahoma and Arkansas: Exploration and Conservation of Subterranean Biodiversity. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012.

Graening, G. O., Michael E. Slay, and Chuck Bitting. “Cave Fauna of the Buffalo National River.” Journal of Cave and Karst Studies 68 (2006): 153–163.

Graening, G. O., Michael E. Slay, and Karen K. Tinkle. “Subterranean Biodiversity of Arkansas, Part 1: Bioinventory and Bioassessment of Caves in the Sylamore Ranger District, Ozark National Forest, Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 57 (2003): 44‒58. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol57/iss1/8/ (accessed September 24, 2019).

Hyman, Libbie H. “Endemic and Exotic Land Planarians in the United States with a Discussion of Necessary Changes of Names in the Rhynchodemidae.” American Museum Novitates 1241 (1943): 1‒12.

———. The Invertebrates: Platyhelminthes and Rhynchocoela. The Acoelomate Bilateria. Vol. II. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1951.

———. “New Species of Flatworms from North, Central, and South America.” Proceedings of the United States National Museum 86 (1939): 419‒439.

———. “North American Triclad Turbellaria, X: Additional Species of Cave Planarians.” Transactions of the American Microscopical Society 58 (1939): 276‒284.

———. “Some Land Planarians of the United States and Europe, with Remarks on Nomenclature.” American Museum Novitates 1667 (1954): 1‒21.

Jenkins, Marie M., and Sue E. Miller. “A Study of Planarians (Dugesia) of an Oklahoma Stream.” Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science 42 (1962): 133‒143.

Kawakatsu, M., and R.W. Mitchell. “Occurrence of Dendrocoelopsis americana (Hyman, 1939) in Soda Water Well, Texas, U.S.A. (Turbellaria, Tricladida, Paludicola).” Proceedings of the Japanese Society of Systematic Zoology 28 (1984): 1‒11.

Levengood. C. A. “Some Notes on the Cave Flatworm, Sorocella americana.” Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science 20 (1940): 33–34.

McAllister, Chris T., Henry W. Robison, and Renn Tumlison. “Additional County Records of Invertebrates from Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 72 (2018). Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol72/iss1/36/ (accessed September 24, 2019).

NatureServe Explorer: An Online Encyclopedia of Life. http://explorer.natureserve.org (accessed September 24, 2019).

Noreña, Carolina, Cristina Damorenea, and Francisco Brusa. Phylum Platyhelminthes. In Thorp and Covich’s Freshwater Invertebrates, edited by James H. Thorp and D. Christopher Rogers. 4th ed. New York: Academic Press, 2015.

Riser, N. W., and M. P. Morse, eds. Biology of the Turbellaria: Libbie H. Hyman Memorial Volume. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1974.

Slay, Michael E., William R. Elliott, and R. Sluys. “Cavernicolous Missouri Triclad (Platyhelminthes: Turbellaria) Records.” Southwestern Naturalist 51 (2006): 251‒252.

Sluys, Ronald, Masaharu Kawakatsu, M. Riutort, and J. Baguñà. “A New Higher Classification of Planarian Flatworms (Platyhelminthes, Tricladida).” Journal of Natural History 43 (2009): 1763–1777.

Tumlison, Renn, and Henry W. Robison. “New Records and Notes on the Natural History of Selected Invertebrates from Southern Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 64 (2010): 141‒144. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol64/iss1/29/ (accessed September 24, 2019).

Tumlison, Renn, Henry W. Robison, and T. L. Tumlison. “New Records and Notes on the Natural History of Selected Invertebrates from Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 70 (2016): 296‒300. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/jaas/vol70/iss1/54/ (accessed September 24, 2019).

Wallen, I. E. “A Land Planarian in Oklahoma.” Transactions of the American Microscopical Society 73 (1954): 193.

Henry W. Robison

Sherwood, Arkansas

Chris T. McAllister

Eastern Oklahoma State College

We have had the long “hammerhead” (spade?) in our yard for some time, but I picked up a different one on the patio today. 4-5 inches long, flat head but body more wormlike, so maybe some other order?