calsfoundation@cals.org

Nick Miller (1846?–1898)

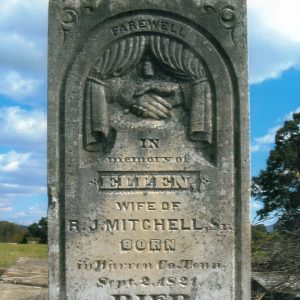

The artistry of stone carver Nick Miller is found in cemeteries throughout northwestern Arkansas. The tombstones he made—crisp and legible well over a century later—employ the mourning symbols of his time: clasping hands, weeping willows, lambs, doves. Yet Miller’s bas-relief motifs and deeply incised lettering exhibit a level of skill and detail not generally found among contemporary carvers.

All that is known about Nick Miller’s origins is that he was born in Germany. He never married, had no relatives in America, and is listed on the 1880 census as an “old batch” at age thirty-six.

In addition to his distinctive carvings, Miller’s tablet-style tombstones are recognizable by his “Nick Miller,” “N. Miller,” or “N. M.” signature at the base. He made foundations, building and chimney stones, and marble mantels and tabletops, and he advertised imported marble, though he also quarried his own stone. He is known to have trained Thomas E. Mitchell, A. C. Key, and brothers William and John Rance Jones to carve and to sign their work. (He was briefly in partnership with Mitchell and, earlier, with William M. Walker.)

In the late 1800s, it was common for Arkansas carvers to move from town to town, staying long enough to fill a backlog of tombstone orders (some for deaths occurring years earlier). Miller, too, moved often.

Miller first appears in the public record in 1872 in Bentonville (Benton County), where he became a U.S. citizen. He is next found in 1877, advertising his Hindsville (Madison County) marble yard. Over the next twenty-one years, he moved back to Bentonville, then to Berryville (Carroll County), to the Boone/Newton county line, to Yellville (Marion County), back to Boone County, and finally back to Berryville in 1893, where he ended his life. His signed tombstones have also been found in Washington and Johnson counties and in extreme southern Missouri.

Some of Miller’s moves may be attributable to problems with alcohol, increasing competition, and the need for access to stone quarries. In 1883, he moved to Wilcockson (later renamed Marble Falls, then Dogpatch, in Newton County) in order to cut tombstones and chimney arch rocks from the quarry that, in 1849, had produced the limestone slab that was Arkansas’s contribution to the Washington Monument.

By 1889, zinc mining prosperity had created a building boom in Yellville, the seat of Marion County. There, Miller made stone foundations for the town’s Methodist Episcopal church, high school, and possibly the courthouse, and he constructed an elaborate red, pink, and variegated marble-sheathed store building for A. S. Layton. (No evidence of this remains. The existing “Layton building” was built in 1903–06.)

In 1890, Miller abruptly left Yellville for Harrison (Boone County); in 1893, he returned to Berryville. There, on August 14, 1898, after drinking heavily, he took his own life at age fifty-two. He had sent for friends (only one man showed up) and swallowed cyanide that he purchased six years earlier for this purpose. He was buried the same day in an unmarked grave in Berryville’s city cemetery, within sight of a dozen tombstones he had carved and signed. In his suicide note, he suggested selling his stone, tools, and photos to the Jones brothers to pay for his coffin. He also stated his reason for dying: “I have not outlived my friends,” he wrote, “but simply tired of making so many new starts in life.”

For additional information:

Burnett, Abby, and Vineta Wingate. “Carvers of Carroll County.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly 53 (September 2008): 22–26, 47.

———. “My Soul From Out This Shadow Shall be Lifted Nevermore: Nick Miller, Tombstone Carver, 1846–1898.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly 53 (June 2008): 17–22.

Burnett, Abby. “Nick Miller, 1846–1898: Tombstone Carver Lies in Unmarked Grave.” The Ozarks Mountaineer 57 (March/April 2009): 52–55.

Abby Burnett

Kingston, Arkansas

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment

Arts, Culture, and Entertainment Methodists

Methodists Nick Miller Carving

Nick Miller Carving  Nick Miller Carving Detail

Nick Miller Carving Detail  Nick Miller Signature

Nick Miller Signature  Nick Miller Carving

Nick Miller Carving  Miller Lamb Motif Carving

Miller Lamb Motif Carving  Nick Miller Carving

Nick Miller Carving

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.