calsfoundation@cals.org

Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad (M&NA)

The Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad (M&NA) was a regional carrier that, at its peak, stretched from Joplin, Missouri, to Helena (Phillips County). The railroad was plagued with weather-induced disasters, periods of labor unrest, questionable decisions by absentee managers and owners, unforgiving topography, economic conditions, fires, and bad luck. After the completion of the line, it existed for only four decades. The M&NA was the victim of a territory that could not produce sufficient revenue to support it. It had tough competition from the Missouri Pacific’s two routes through the region and their stronger traffic connections. The railroad was also constructed in a less-than-substantial fashion, which led to its many washouts, floods, and infrastructure failures.

The railroad began as a connection from Seligman, Missouri, on the St. Louis–San Francisco Railway (Frisco). Former governor Powell Clayton was the chief promoter of the Eureka Springs Railway, which reached its namesake town of Eureka Springs in February 1883. Earnings began to taper off by the century’s end, partly due to decreased travel to the resort spa. Interest grew in serving the lead and zinc mining districts of north-central Arkansas. In May 1899, the Eureka Springs Railway conveyed to a new organization, the St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad. The original plan was to build the line to Little Rock (Pulaski County) along today’s U.S. 65 corridor. The first extension reached Harrison (Boone County) in April 1901, and Leslie (Searcy County) received service in September 1903. In 1906, the railroad was reorganized as the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad Co.

Attention turned to building northward, reaching Neosho, Missouri, in March 1908, and service was later extended to Joplin, accomplished through trackage rights over the Kansas City Southern Railway (KCS). Southward expansion then began, reaching Searcy (White County) in July 1908. By year’s end, the M&NA was in operation from Joplin to Kensett (White County), thus becoming a “bridge line” from the KCS to the north, to the Iron Mountain Railroad in central Arkansas. The line was finally completed to Helena at a construction cost of $6 million. Service began over the entire M&NA on March 1, 1909. Pullman sleeper service was initially offered on a Kansas City, Missouri, to Helena route. Due to irregular dependability in its early years, the railroad’s acronym came to stand for “May Never Arrive.” After several years of running deficits, the railroad entered receivership in April 1912.

Gas-electric motorcars were acquired for use in service from Joplin to Eureka Springs (Carroll County) and from Heber Springs (Cleburne County) to Helena. Due to the adoption of the eight-hour workday and 100-mile runs, Harrison and Heber Springs were made division points, leading to the relocation of the main office and shops to Harrison in 1913. Through a policy of “spending money to make money,” the railroad was put in first-class condition. In August 1914, however, a miscommunication in train orders led to a terrible head-on collision near Tipton Ford, Missouri, killing thirty-eight passengers and five crew members. By 1916, the railroad was experiencing operating earnings, but the government’s takeover of the railroads in 1917 to support the World War I effort would prove detrimental. Due to a policy guaranteeing income based on a railroad’s 1914–1917 average, the M&NA suffered a period of loss.

In February 1921, over wage cuts brought on by the postwar recession, the M&NA experienced the longest and most bitter strike ever to hit a U.S. railroad. Vandalism and intimidation were rampant, and the railroad remained shut down for eight months. It was reorganized in April 1922 and resumed operations. Labor unrest persisted until quelled by a violent citizens’ uprising, which included a lynching.

By the mid-1920s, the M&NA had begun a wide-ranging and needed rehabilitation of the line. Prosperity seemed to be near when the Flood of 1927 severely damaged much of the railroad’s infrastructure, especially in eastern Arkansas. The M&NA entered receivership for a second time. The Depression years ensued, along with numerous bridge failures. Foreclosure and sale of the line followed. In April 1935, the Missouri and Arkansas Railway Co. (M&A) was organized to take over what had been M&NA property.

The M&A acquired two streamlined motorcars in June 1938 to replace the steam-powered passenger trains. Bad fortune struck the railroad yet again when, in December 1941, the general offices at Harrison were destroyed by fire, with the shops burning a few months later. The World War II years provided increased tonnage and revenues for the railroad, but in July 1944, the M&A suffered a short labor strike over wage demands. In December 1944, the back shop building at Harrison burned. In April 1945, White River flooding wreaked havoc on the right-of-way near Georgetown (White County). This washout persisted over the summer and into October. At the same time, business was dropping as a result of the war’s end, and this spelled the end for the M&A. Operations over the railroad ended in September 1946, with the longest abandonment of railroad track that year. Salvage of much of the M&A began in April 1949.

Two sections of the former Missouri and Arkansas Railway returned to service under new ownership. The Seligman, Missouri, to Harrison portion was operated by the Arkansas and Ozarks Railway in diesel-hauled freight service from February 1950 through May 1960. The Helena to Cotton Plant (Woodruff County) section operated as the Helena and Northwestern Railway from October 1949 to November 1951, using steam equipment. Finally, a six-mile stretch of the Helena and Northwestern Railway from Cotton Plant to Fargo (Monroe County) was operated by the Cotton Plant-Fargo Railway, connecting with the St. Louis-Southwestern Railroad at Fargo. The Cotton Plant-Fargo Railway existed from April 1952 into the 1970s and was the last vestige of the old M&NA to be abandoned.

For additional information:

Barnes, Kenneth C. Mob Rule in the Ozarks: The Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad Strike, 1921–1923. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2024.

———. “Railroad Rage.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 23, 2023, pp. 1D, 6D. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/jan/23/100-years-ago-in-arkansas-1000-angry-men-crushed/ (accessed January 23, 2023).

Fair, James R., Jr. The North Arkansas Line: The Story of the Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad. Berkeley, CA: Howell-North Books, 1969.

Handley, Lawrence R. “Settlement across Northern Arkansas as Influenced by the Missouri & North Arkansas Railroad.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 33 (Winter 1974): 273–292.

Hull, Clifton E. Shortline Railroads of Arkansas. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1969.

Kubat, Tim. “Derailments and Tragic Wrecks on the M & NA.” Boone County Historian/Oakleaves 20 (September–December 2020): 29–38.

Motherwell, David. “The Missouri and North Arkansas Railroad.” Carroll County Historical Quarterly 49 (December 2004): 161–164.

H. Glenn Mosenthin

Arkansas Railroad Club

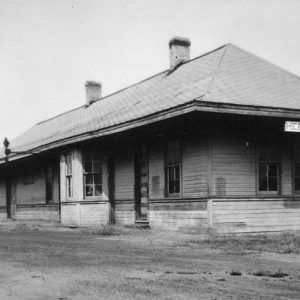

Alpena Depot

Alpena Depot  Alpena Depot

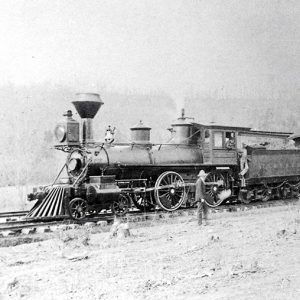

Alpena Depot  Engine No. 8

Engine No. 8  Gilbert Train Depot

Gilbert Train Depot  Grading Work

Grading Work  Harrison Roundhouse

Harrison Roundhouse  Heber Springs Depot

Heber Springs Depot  M&NA Train at Kensett

M&NA Train at Kensett  Marshall Depot as Home

Marshall Depot as Home  M&NA Engine at Kensett

M&NA Engine at Kensett  M&NA Motorcar Thomas C. McRae

M&NA Motorcar Thomas C. McRae  Shirley Depot

Shirley Depot  St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad

St. Louis and North Arkansas Railroad  White County Rail Heritage Center

White County Rail Heritage Center

A few of the main buildings remain in Harrison and have been repurposed as a hardware store and lumber storage buildings.

My mom lived in the depot as a child in the 1920s. Her father, Thomas Vernon Cash, was a line foreman for the railroad. Her grandparents lived across the field behind the railroad. Mom told me that hobos would sometimes ask her mother for a bite to eat, and she always had something for them. Mom died about five years ago. I would have loved to have taken her to the opening of the museum.