calsfoundation@cals.org

Marianna (Lee County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34º46’25″N 090º45’27″W |

| Elevation: | 228 feet |

| Area: | 3.61 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 3,575 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | February 7, 1878 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

627 |

1,126 |

1,707 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

4,810 |

5,074 |

4,314 |

4,449 |

4,530 |

5,134 |

6,196 |

6,220 |

5,910 |

5,181 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4,115 |

3,575 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

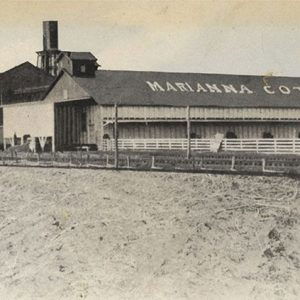

Marianna, the county seat of Lee County, is situated along the L’Anguille River in eastern Arkansas. It has long been primarily an agricultural community, a center especially for cotton production, and also has a history that highlights many of the troubles of the Arkansas Delta region, both in economy and in race relations.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

Marianna was founded as the village of Walnut Ridge in 1848 by Colonel Walter H. Otey. Its name was changed to Marianna four years later, and, by 1858, the city was relocated three miles downstream on higher ground and where the L’Anguille River was navigable throughout the year. Steamboats connected the young city to important Mississippi River ports such as Memphis, Tennessee, transporting cotton out and manufactured goods in. The Plow Boy was the first steamboat to venture up the L’Anguille.

Civil War through the Gilded Age

During the Civil War, a number of military actions took place in Lee County following the July 1862 occupation of Helena (Phillips County) by Federal forces. Probably the largest military action to take place near the city occurred on November 8, 1862, when Captain Marland L. Perkins of the Ninth Illinois Cavalry, along with the Third and Fourth Iowa cavalries, marched from Moro (Lee County) to Marianna, encountering Confederate resistance along the way, including an attack by 500 mounted troops at La Grange (Lee County). However, Union forces were able to beat back the Confederate charge, killing an estimated fifty soldiers throughout the day.

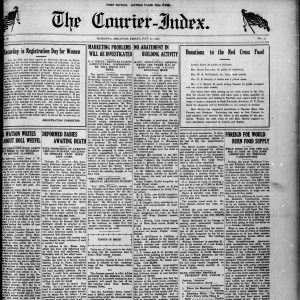

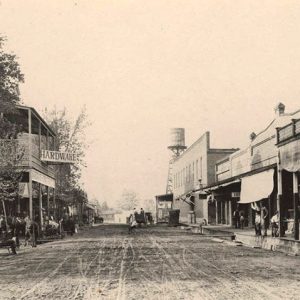

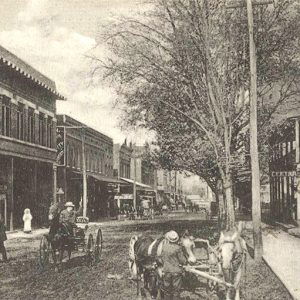

In 1868, during Reconstruction, Marianna was located within one of several counties placed under martial law by Governor Powell Clayton because of terrorist acts committed by the Ku Klux Klan. Under the sponsorship of African American state representative William Hines Furbush, Lee County was created by the state legislature in April 1873, and Marianna was named the county seat. In 1874, the first brick store was erected and the first edition of the Marianna Index newspaper was published. A few years later, the rival Lee County Courier was founded. In 1879, in the midst of a statewide yellow fever scare, the city enforced a strict quarantine and thus managed to escape relatively unharmed. Two years later, the first kerosene lamps were installed along the streets, and the Helena and Iron Mountain Railroad connected Marianna with Helena and Forrest City (St. Francis County). Marianna Male and Female Academy was established in 1884, and it lasted until 1905, when it burned to the ground.

In 1881, an African American man named Dave Ramsey was lynched for having allegedly attempted to assault a white girl. Two years later, another Black man, Jesse Howard, was lynched for alleged arson.

Early Twentieth Century

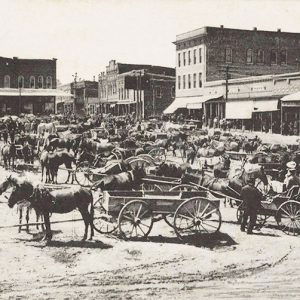

On February 3, 1905, the white public school burned. Street paving began in 1908, at least in white neighborhoods; until African Americans began challenging the system of white supremacy, they were often denied such services. In 1910, a statue of Robert E. Lee, after whom the county was named, was erected in City Park, having been donated by the Daniel C. Govan Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. In 1913, the Missouri Pacific Railroad completed a line connecting Marianna with Memphis. This was also the same decade that an African American family opened and operated what is now known as Jones Bar-B-Q Diner, which continues to this day as an award-winning restaurant. Marianna became a first-class city in February 1914. In 1917, the Index and the Courier newspapers were consolidated. An August 1918 blaze downtown destroyed fourteen buildings and caused $1 million of damage.

In 1919, an African American man named Alexander (Alex) Wilson was lynched for allegedly murdering a white woman.

The Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station (AAES) established in Marianna a research station focusing on cotton in 1926; this is now the Lon Mann Cotton Research Station. However, the city was hit hard by the Great Depression and the ever-declining value of cotton. The Farm Security Administration, a New Deal agency, was active in Lee County during the Depression, taking offices in the Mixon Building in Marianna and conducting extension service throughout the county. Other New Deal agencies working in the county included the Public Works Administration (PWA) and Works Progress Administration (WPA).

Marianna has long been prone to flooding. Significant inundations occurred in 1912; during the Flood of 1927, when an estimated 20,000 people needed relief; and ten years later during the Flood of 1937, when the L’Anguille and St. Francis rivers overflowed.

World War II through the Faubus Era

Many young men from Marianna enlisted in the military during World War II. However, the city had enough of a manufacturing base that it did not lose much population following the war, and agricultural operations continued to expand. In 1952, the Lee County Grain Drying Cooperative was founded.

Marianna, like other cities in the Delta region, had a significant Chinese American population during the twentieth century. In the 1940s, the Chinese ambassador to the United States visited Marianna as a guest of the local Fong family.

As lawyer and historian Grif Stockley wrote, “Marianna in Lee County in the heart of the Delta epitomized the racial problems of the state in the late 1960s and early 1970s.” When representatives of Volunteers in Service to America (VISTA) arrived in Marianna in the 1960s to aid the poor of the county, they encountered fierce resistance from local whites in their attempts to establish a local health clinic that would serve African Americans. However, with the leadership of Olly Neal Jr., the Lee County Cooperative Clinic became a reality and began operation in March 1970.

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform

In response to federal pressure from the U.S. Department of Justice during the late 1960s to desegregate its public schools, the county school board scrapped its “freedom of choice plan” in 1970. The previous year, however, the private Lee Academy was established in Marianna; one of many “segregation academies” that emerged in the Mississippi River Delta region of the country, it attracted a significant portion of the school district’s white children, thus ensuring that public schools remained largely segregated. Lee Academy is not accredited by the state but rather by the Mississippi Association of Independent Schools, founded in 1968 as the Mississippi Private School Association.

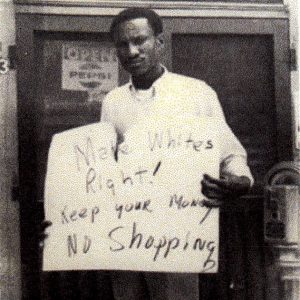

In June 1971, African Americans in Marianna began a boycott against local white merchants, demanding that jobs be opened up to them. Fights began to break out between white and Black residents, and Governor Dale Bumpers responded by sending in the National Guard and ordering a curfew. In January 1972, Black students began a school boycott, wanting a fired Black teacher reinstated and the implementation of Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebrations. A study done at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR) put the economic damage of the boycott into the millions. These events initiated a wave of Black political activism. Roy C. “Bill” Lewellen was elected a city alderman in the 1980s and later became the county’s first Black state senator since Reconstruction. In 1994, Marianna elected Robert Taylor as its first Black mayor.

In August 1973, the Marianna/Lee County Airport began operations. This airport features two runways and averages sixty-nine operations a day. The McClendon, Mann & Felton Gin is situated west of the city and processes cotton from the area. Many of the city’s larger businesses are related to area agriculture. In the last decades of the twentieth century, Marianna began experiencing a population decline similar to that of the Delta overall, though not on as large a scale as in Helena-West Helena to the south.

The Lee County Cooperative Clinic built a new facility and was renamed the Olly Neal Community Health Center in 2024.

Attractions

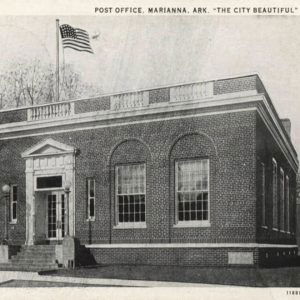

Marianna has a number of local properties listed on the National Register of Historic Places: the General Robert E. Lee Monument in City Park; the J. M. McClintock House and the W. S. McClintock House, both of which were designed by noted architect Charles Thompson; the Marianna Commercial Historic District; as well as the courthouse and the National Guard armory. The St. Francis National Forest is located east of Marianna. The St. Francis National Scenic Byway runs through the forest. The Marianna Waterworks, made in the 1930s, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Famous Residents

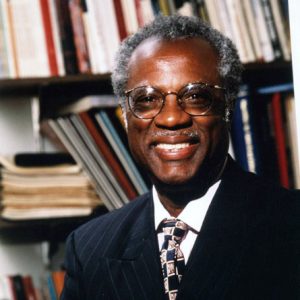

Philip McCulloch was a congressman in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Actor Minor Watson, who had roles in more than 100 films, was born in Marianna in 1889. Robert McFerrin Sr., the first Black man to appear in an opera at the Metropolitan Opera house in New York City, was born in Marianna in 1921. James Albert Banks, known as the “father of multicultural education,” was born near Marianna in 1941 and later graduated from Russa Moton High School. Mildred Griggs, economics scholar, was also born in Marianna, in 1942. C. Calvin Smith was the first Black professor at Arkansas State University (ASU). Anna Strong was a nationally recognized leader in education. Writer, attorney, and historian Grif Stockley grew up in Marianna, graduating from high school in 1962. Rodney Earl Slater, who served as the U.S. secretary of transportation, also grew up in Marianna and attended school there. Football players Dennis Winston and Charles Flowers hail from Marianna. In addition, federal judges Catherine Eagles and Curtis Lynn Collier grew up in Marianna. Everett Cook was a successful businessman who distinguished himself during both World War I and World War II. Michael Lewellen was a leader in the field of corporate communications beginning in the 1980s.

For additional information:

Adler, William M. Land of Opportunity: One Family’s Quest for the American Dream in the Age of Crack. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1995.

Apple, Nancy, and Suzy Keasler, eds. History of Lee County, Arkansas. Dallas: Curtis Media Group, 1987.

Couto, Richard A. “The Value of Improved Self-Worth, Lee County, Arkansas.” In Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Round: The Pursuit of Racial Justice in the Rural South. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991.

Franklin, Stephen James III. “The Marianna Boycott: Healthcare, Political Organization, and Federal Intervention in the Arkansas Delta.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2022.

Marianna, Arkansas. https://www.arkansas.com/marianna (accessed July 1, 2024).

Morgan, Gordon D. “Marianna: A Sociological Essay on an Eastern Arkansas Town.” Jefferson City, MO: New Scholars Press, 1973.

Stockley, Grif. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

Wintory, Blake J. “Environmental and Social Change in Lee County, Arkansas, and the St. Francis River Basin, 1865–1905.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2005.

Staff of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas

On May 14, 2012, the federal Character Education Partnership (CEP) recognized Lee County School District from Marianna as a 2012 Promising Practice for its “Our Story” Youth Leadership Conference practice. “Our Story” Youth Leadership Conference is a unique service learning project that began in Marianna on March 9, 2010. The conference started as a one-day event, but has now grown into an entire weekend, with other events scheduled throughout the year. Each year, we work to bring former graduates back to Marianna to pour into the community’s youth, parents, and educators. Since the inception of “Our Story,” 27 graduates have returned to share their stories of growing up and overcoming the negative events Marianna has been known for since the late 1980s. The school district has about 1,200 students grades PreK-12. Each year in March, we spend at least two hours at each school motivating, encouraging, and inspiring the students, educators, and parents. We always provide the students with trinkets that have the “Our Story” logo on them as a reminder that everyone has a story. The highlight of the conference is awarding at least five students with a $500 scholarship each year. The ultimate vision of “Our Story” is for the recipients of the scholarship to collectively award a scholarship to a deserving senior the following year, following the motto, “If you leave and grow, you can come back and plant” – Marquis Cooper. This year’s winning practices include unique anti-bullying programs, successful integration of academics and character, self-motivation and goal-setting strategies, service-learning activities, and community outreach.

(2011) For years, the city of Marianna has been overshadowed by negative stories that caused many people to overlook all the great things for which the town is responsible. The story of the Chambers brothers in the late 1980s (leaders of a Marianna to Detroit crack cocaine connection) created a dark shadow that the city has never been able to live down. Recently, stories of Curtis Vance (convicted of killing KATV anchorwoman Anne Pressly), Maurice Clemmons (killed by police who sought him for the shooting deaths of four police officers in Washington State), and now Operation Delta Blues (a major drug raid that netted 70 indictments) further validated the point that Marianna was only producing thugs, murderers, and drug dealers. It was stories and events like these that ignited the “Our Story” Youth Leadership Conference. We felt something positive and encouraging needed to be done to show people that a new era of those who are concerned about the community has now arisen. On March 12, 2010, the alumni of the Lee County School District held our 1st Annual “Our Story” Youth Leadership Conference. We had graduates from the classes of 1990-2001 come back and share in this awesome event. March 11, 2011, was the 2nd Annual “Our Story” Youth Leadership Conference. We had seventeen former graduates from six states who played a major role in making this event a success. The highlight of the conference was having enough funds to sow $500 scholarships into the lives of five very deserving students. Our goal this year is to host a three-day event March 9-11, 2012. It is my desire that others will join the “Our Story” movement so we can change the image of the past and move forward into the future.