calsfoundation@cals.org

Marianna Boycotts of 1971–1972

In the early 1970s, African Americans in the rural Delta community of Marianna (Lee County), lacking representation in any of the town’s governmental councils, undertook a series of boycotts in an effort to end Marianna’s continuing segregation and gain the legal and educational equality that earlier Supreme Court rulings and federal legislation had promised. The multi-faceted effort included a boycott by the Marianna High School’s African-American basketball players as well as economic boycotts of white merchants—all measures seeking to combat the town’s continued refusal to abide by the laws of the time mandating equal rights and opportunities for all.

At the time of the boycotts, Marianna and Lee County were sixty percent Black, but many stores refused to give the area’s African Americans full access, and Black locals had no direct representatives on any governmental bodies. In addition, hiring practices reflected decades of Jim Crow segregation while also continuing the discriminatory patterns that had long been the norm. Finally, Marianna’s Black citizens had major concerns about the local schools, at which minimal desegregation efforts had only recently been started. Indeed, the 1970–1971 school year was the first academic year in which Marianna School District operated as a unified desegregated district. However, from the beginning, there was controversy, with allegations of favored treatment for white students heading the list of grievances. But such discontent notwithstanding, the 1970–71 school year had gone relatively smoothly, although almost 200 white students left the public school to attend the nearby all-white Lee Academy, a private school created in direct response to legal demands to desegregate (colloquially called a “segregation academy”).

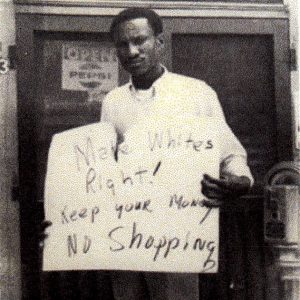

In response to all of these issues, on June 11, 1971, African Americans in the town, under the label of the Concerned Citizens group, began a boycott of the town’s white-owned businesses. According to some reports, the catalyst was the arrest of a Black woman, Quency Tillman, for supposedly “talking back” to a white waitress at a local pizza place. The day after the incident, the boycott began. The support for the effort was broad and immediate, with the few who did not initially participate apparently being unaware that the effort was going on. As the summer progressed, there were numerous incidents of violence. Charges and countercharges flew, traded amidst ever increasing tensions. For one two-week period, the city was under an evening curfew.

With the school year getting under way, in October a group of about 600 white townspeople responded to a call from the state’s Citizens Council and gathered in Marianna’s Community House to consider a response. At the meeting, organizers distributed a list of the more than twenty-five businesses that were resisting the boycott. In addition, an active campaign was undertaken to get outsiders to come to Marianna and shop at places that organizers felt were being harmed by the boycott. At the Community House gathering, additional businesses asked that they be included on the list. While the Citizens Council organizers claimed to be concerned not just about the white-owned businesses that were being targeted but also about Black workers, some of whom had been laid off in response to the boycott, the main focus was in crushing the boycott without having to address the grievances that motivated it.

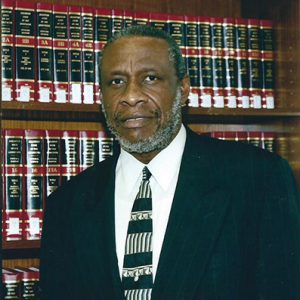

White opponents of the boycott also noted that Olly Neal Jr.—a graduate of the segregated Marianna high school who had left town to go to college, served in the U.S. Army in Vietnam, and then returned to the area in 1970 to open a healthcare clinic with the help of the federal VISTA program—was one of the leaders of the boycott, along with Neal’s brother Prentiss Neal and Rabon Cheeks. Olly Neal’s involvement led them to call on Governor Dale Bumpers to discontinue VISTA’s involvement in Arkansas where he could. The governor refused, and the stalemate continued.

As fall moved into winter, the boycott added another dimension. In early January 1972, a large group of Black students at Lee High School staged a series of protests against what they perceived as the favored treatment of whites as well as the administration’s refusal to undertake a formal observance of the birthday of civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. Everything came to a head after a January 13 incident in which police dispersed about 200 students from school grounds, where many of them had been involved in a protest aimed at achieving a number of changes at the majority-Black school. While arrest warrants were issued for over 100 students who were accused of disrupting school activities, a misdemeanor, the students and parents alleged that the police, as well as firemen, had not only beaten students but had turned fire hoses on them. Using one of the few points of leverage the area’s Black population possessed, Black high school basketball players initiated a boycott the next day, announcing their refusal to play until change was achieved. The first forfeited game came on January 14, when the team’s Black members refused to suit up. With all but one of the team’s members being Black, the boycott by the team’s Black members meant that the school had to cancel the rest of the schedule, which it finally did in mid-February.

As the boycott continued, the leaders presented the city’s white leaders with a list of approximately forty demands. These included the hiring of more Black workers in a range of jobs and official posts, as well as the dismissal of some of the town’s long entrenched and resistant white officials. The boycott leaders also sought an end to the discrimination that marked the way businesses operated in Marianna. Soon afterward, representatives from both the Black and white communities asked for the creation of a gubernatorial task force that would be empowered to go to Marianna, investigate the situation, and offer solutions.

The boycott was ended on July 25, 1972, with Black leaders declaring that adequate progress had been made, at least enough to justify the end of the effort. In addition to opening up the town’s commercial establishment, the boycott had had a measurable effect on the town’s economic establishment. It was reported that twelve retail stores had either gone out of business or closed their doors before they were forced to do so. Meanwhile, legal challenges to the desegregation of the town’s schools would continue into 1977.

For additional information:

“The Boycott of Marianna Lee High School’s Basketball Team: Part 2.” The Sports Seer, January 18, 2018. http://www.thesportsseer.com/boycott-marianna-lee-high-schools-basketball-team-part-2/ (accessed September 25, 2020).

Couto, Richard A. Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Round: The Pursuit of Racial Justice in the Rural South. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991.

Franklin, Stephen James III. “The Marianna Boycott: Healthcare, Political Organization, and Federal Intervention in the Arkansas Delta.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2022. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/4678/ (accessed December 1, 2023).

Friedman, Monroe. Consumer Boycotts: Effecting Change through the Marketplace and Media. New York: Routledge, 1999.

Morgan, Gordon D. “Marianna: A Sociological Essay on an Eastern Arkansas Town.” Jefferson City, MO: New Scholars Press, 1973.

Neal, Olly, Jr. OUTSPOKEN: The Olly Neal Story. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2020.

Shannon, George. “Citizens Counter Black Boycott.” The Citizen, December 1971.

Stockley, Grif. Ruled by Race: Black/White Relations in Arkansas from Slavery to the Present. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2008.

William H. Pruden III

Ravenscroft School

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century)

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century) Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Olly Neal

Olly Neal  Prentiss Neal

Prentiss Neal

Interesting, I was born in Marvell, left at a young age and somehow returned in 1980 till 1988. From Marvell I did live in Marianna but know very little about the history of my birth state. Reading this, looking at the time line tells me nothing changed, and I guess it never will. It’s a shame how we as people of color went through so much to have freedom, yet things changed but we are still near the bottom of the totem pole.

I’m just ecstatic to read some details I didn’t know about the boycott. I remembered the schools being boycotted, but not the businesses. I also remembered the fear surrounding the effort, but the bravery was more pronounced. And I hear Lee Academy is still segregated.

Unaware of the boycott in 1971 while visiting from Kansas City, Kansas, we were home (Moro) to bury my farther. We had gone to the market in Marianna to shop for groceries. On leaving we were approached by an organizer, informing us of the boycott, asking us not to shop there again. We apologized and honored their request.

My black family moved to Marianna around 1973, when I was only eight. I remember children talking about the boycott and how many of my classmates had to repeat a grade because they missed school because of the boycott. I lived in Marianna until I went off to college in 1982.

This was a very great and interesting read for me. I lived there all those years and never knew the full story. I even remember some of the people named in this document.