calsfoundation@cals.org

Lessie Stringfellow Read (1891–1971)

Lessie Stringfellow Read was an early champion of women’s rights, a writer for six national periodicals of her day, a correspondent for two large newspapers, and a newspaper editor herself. She was a founder of the Women’s Suffrage Association of Washington County and was an officer for the local Red Cross during World War I. In addition, she served many years as national press chairperson for the largest women’s organization of the early twentieth century, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs.

Lessie Read was born Mabel Staples on January 3, 1891, in Temple, Texas, to William and Lillian Staples. Both her parents died from a fever when she was two years old, and the renowned horticulturist Henry Martyn Stringfellow and his wife, Alice, adopted her. The Stringfellows, who had lost their only child, a nineteen-year-old boy named Leslie, to malaria in 1886, had been friends of the Staples family.

According to the Stringfellows, their deceased son made himself known to his parents by means of spirit communications during the years Mabel lived with them. (Henry Stringfellow was a member of the Rosicrucian Society, a spiritualist organization, but his wife did not believe in spiritualism until her experiences with her dead son began.) The parents maintained that their son and the little girl jointly requested that her name be changed to “Lessie.” Although little Lessie was not allowed to attend the family’s daily séances, numerous messages for and about her were received.

Stringfellow grew up on the family farm and orchard that her adopted father had established in 1881 outside the gulf coast village of Hitchcock, Texas. He held three college degrees, and his wife, Alice, had attended Hunter College for Women in New York, and Lessie received her basic education at home from her adopted parents. During her teenage years, arrangements were made for her to be privately tutored during the summers by a professor from Leland Stanford University (now Stanford University). While still a teenager, Read worked as a correspondent for the Houston Chronicle, contributing articles on local news from her area of the state.

In September 1910, Stringfellow married James Read, a pharmacist. The couple moved with the Stringfellows to Fayetteville (Washington County) in 1911, where her adopted father died a year later. The following year, Read’s husband disappeared. Unsubstantiated rumors of that time suggest that he had left town abruptly under suspicion of having embezzled money from a Fayetteville drugstore where he was employed.

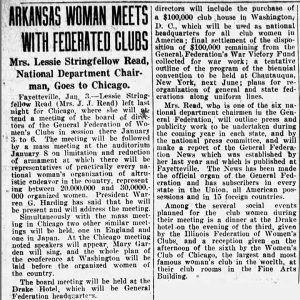

Without the responsibilities of a being a wife, but retaining married status, Read was able to move unimpeded in a society that discriminated against single women. By 1915, at age twenty-four, she was involved in the women’s suffrage movement as a founder of the Washington County Women’s Suffrage Association and president of the Fayetteville Equal Suffrage Association. She was named national press chairwoman in 1916 for the largest international women’s organization of that time, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, and was also editor of the organization’s General Federation News. In 1918, the GFWC’s biennial convention was held in Hot Springs (Garland County), and Read was primary coordinator for the event. From 1916 to 1926, she served as press director for national conventions of the GFWC and, in that capacity, met and spoke with many national figures, including Thomas Edison, John D. Rockefeller, and Carrie Chapman Catt, who in 1900 replaced Susan B. Anthony as president of the American Woman’s Suffrage Association. Catt stayed with Read at her home in Fayetteville while in town for a speaking engagement.

Read was working as a journalist for the Fayetteville Democrat in 1918 when its editor, J. D. Hurst, resigned his position to join the American forces in World War I. She became the editor of the newspaper. She offered to resign when Hurst returned from the war. Hurst declined, choosing instead to work as the newspaper’s business manager, and Read was editor of the Fayetteville Democrat for the next twenty-seven years.

During her years with the paper, Read worked in an unconventionally feminine atmosphere: she was the editor, Roberta Fulbright was the owner, and Maude Gold was the paper’s only full-time reporter.

In 1933, the newspaper became embroiled in a battle with a corrupt political machine that had operated in Washington County for years. Sheriff Harley Grover and County Circuit Court Judge John S. Combs were protecting men who operated illegal stills and were running a car theft ring within the county. Because these high-ranking officials were corrupt, little legal recourse existed to combat this corruption until Fulbright and Read effectively used the newspaper to galvanize local churches and civic organizations into forming the Good Government League, which ultimately forced out the corrupt officials and voted in its own candidates. Threats were received frequently at the newspaper, and one of Fulbright’s employees began carrying a gun, but Fulbright, Read, and Gold did not back down.

In later years, Read was a founding member of the Washington County Historical Society, an occasional correspondent for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the Memphis Commercial Appeal, as well as the Associated Press and other news syndicates. She wrote for Good Housekeeping, Deliniator, Southern Women’s Magazine, Country Gentleman, Woman Citizen, and the Saturday Evening Post. Her articles covered subjects as diverse as photography, poetry, and women’s rights. She published a book by Arkansas poet George Ballard, as well as her adoptive mother’s book, Leslie’s Letters to His Mother. She also edited a book of poetry by Roberta Fulbright, with whom she shared a close friendship, and assisted folklorist Vance Randolph with collecting original folk tales of the Arkansas Ozarks for the Library of Congress.

Read remained the editor of Fayetteville’s main newspaper until her retirement in 1945. By the late 1930s, the paper had changed its name to the Northwest Arkansas Times.

She continued living alone in the family mansion until becoming senile during the late 1960s. She spent her final years at the Fayetteville City Hospital and died on May 28, 1971, at the age of eighty. She is buried at Evergreen Cemetery in Fayetteville.

For additional information:

Chism, Stephen. The Afterlife of Leslie Stringfellow: A Nineteenth-Century Southern Family’s Experiences with Spiritualism. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2006.

———. “The Very Happiest Tiding: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Correspondence with Arkansas Spiritualists.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 59 (Autumn 2000): 299–310.

Lessie Stringfellow Read Papers. Special Collections. University of Arkansas Libraries, Fayetteville, Arkansas.

Youngblood, Joshua Cobbs. “’Miss Lessie’ Was There: Fayetteville’s Renowned Organizer and Newspaperwoman, Leslie Stringfellow Read.” Flashback 70 (Fall 2020): 98–109.

Stephen Chism

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Lessie Stringfellow Read Article

Lessie Stringfellow Read Article  Stringfellow-Read-Feathers House

Stringfellow-Read-Feathers House

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.