calsfoundation@cals.org

Latinos

aka: Hispanics

The Latino population in Arkansas, which began its rapid growth in the 1980s, has created significant political, economic, and social modifications within the state. Latino food and music, as well as bilingualism, have become common in several regions of the state. Numerous industries and economic ventures have prospered since the mid-1990s due in large part to the contributions of the immigrant workforce.

The Latino influence has changed many towns and cities dramatically. In cities such as Rogers (Benton County) and Springdale (Washington and Benton counties), Latinos make up more than thirty percent of the total population, creating a cultural impact in the area. Latino restaurants and businesses with Spanish signage are now seen in many Arkansas towns and cities. In 2022, the nation of El Salvador established a consulate in Springdale.

According to the Arkansas Department of Education for the school year 2006–07, thirty-eight percent of students in the Springdale School District were Latino (6,258); Latino students made up thirty-seven percent of the Rogers School District (4,912) and 22.4 percent of the Fort Smith School District (3,059). These districts increased their English as a second language (ESL) programs and recognized that many of these students speak Spanish among family and friends in addition to English they speak at school.

History

Hispanic immigration into the state might be said to have begun with the expedition of Spanish navigator and conquistador Hernando de Soto (1496–1542), who explored what would become the Southeastern United States searching for gold, silver, and other valuable goods.

Some scattered Latinos were reported to settle in Arkansas in early 1890s but most moved, leaving no trace of their Latino heritage. When the first Latinos arrived in Arkansas, they lived at the bottom of the socio-economic system, in part due to a lack of skills, education, or knowledge of the English language. Even today, many Mexican and Central American immigrants do not have a high school degree.

Immigrants often worked as field hands in agricultural industries. Writer John Grisham in his novel A Painted House describes how in rural northeastern Arkansas, Mexican farmers picked cotton in the early 1950s. The establishment of small diverse industries in the 1960s and the commercial and residential construction boom in central and northwest Arkansas since the 1980s created the demand for hundreds of new workers. These opportunities attracted Latinos from neighboring states. As the poultry industry expanded in the early 1990s in Arkansas’s northwest and southeast regions, the need grew for unskilled laborers willing to perform grueling, low-paying jobs. The jobs were filled largely by the Latino population.

On October 1980, Fidel Castro permitted about 125,000 Cubans to exit their country from the port of Mariel. A large portion of these refugees, named the “Marielitos,” quickly began new lives with the help of relatives already in the United States, especially those residing in Florida. Others were moved to processing centers, including Fort Chaffee near Fort Smith (Sebastian County), before they were allowed to remain in the country. Records show that 25,390 Cubans went through Fort Chaffee in a two-year period, but only a handful remained in Arkansas after their processing and release.

Currently, northwestern Arkansas is home to approximately half of the state’s Latinos, a region that was almost entirely white and where African Americans have not represented a significant population. Some explain the absence of Black residents in the region by noting that the northwestern rocky soil was not conducive to the sort of agriculture that had been practiced on slave plantations in the South; too, many of the Black communities that did exist in the region were driven out during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Consequently, Latinos had an opportunity to fill the gap in this economic segment, which is mainly represented by the poultry and timber industries.

Small grocery stores and Mexican restaurants are seen everywhere in Arkansas, including rural areas. In the larger cities, Latinos are moving up the economic scale and holding better jobs, owning homes, and becoming business entrepreneurs and managers.

Culture

Members of the Latino community enjoy large extended families, and these networks serve a variety of functions, including jobs, business, healthcare, religion, celebrations, and traditions. The Latino concept of family extends to friends, neighbors, and organizations that make up their community. Also of importance are relatives left behind in their native country. They feel an obligation to provide moral and financial support. Work is viewed as a means to meet family responsibilities and obligations.

Latino households in Arkansas consist frequently of at least five people. Half of Hispanic teens live with both biological parents until marriage and are more apt to marry young. Divorce rates are low, motherhood is important, children are expected to care for family elders, and the majority of preschoolers are cared for by a relative. Religion is central to marriage and family life, and is a source of help in times of trouble. The vast majority of Latino Americans are Catholic, and in many areas, the Diocese of Little Rock provides Spanish-language Mass and ministries. Numerous Latinos who arrived from other states had adopted Protestant faiths that offered them a less-formal spiritual environment as well as ministers/pastors whom some consider more in tune with Latino immigrants’ life experiences. More bilingual preachers have started to arrive in Arkansas to offer their support and services to this community in their native language.

Once the first Latino immigrants settled in Arkansas and located job opportunities with little prejudice, the word passed to relatives and friends in other states, mainly California and Texas, and more Latino newcomers entered and settled in the state. As the Latino population expanded, it adapted to the new environment. No longer were Latinos concentrated only in certain areas where a Latino community already existed. They spread into new areas of the state, urban as well as rural, which provided jobs and development opportunities. Latino workers appeared all over Arkansas—Hope (Hempstead County), De Queen (Sevier County) Dumas (Desha County), Jonesboro (Craighead County), and even in the southern Delta region.

Entrepreneurship is very high among Latinos, whether educated or not. For Latinos to fulfill their “American dream” means that they are economically self sufficient. The number of small enterprises owned by Latinos reached one percent of all small businesses in the state in the year 2002. These enterprises are largely represented by restaurants and grocery stores. Latino labor has a great presence in service businesses, mainly represented in construction, landscaping, and other agriculture activities. According to a study published in 2013 by the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, the economic contribution of immigrants—primarily Latino—in 2010 was $3.9 billion, up considerably since 2004, when the total impact was $2.9 billion. The report also noted that for every dollar the state spent on services to immigrant households in 2010, it received seven dollars in immigrant business revenue and tax contributions.

In recent years, Latino professionals have joined the labor forces of corporations, financial institutions, and universities, including Walmart Inc., Tyson, AT&T, the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, and Bank of America. The new entrepreneurs and professionals have begun to change the profile of the Latino population in Arkansas and are becoming more recognizable and respected. Also, the large population (256,847 as of the 2020 census) has motivated the advent of Latino mass communications media, such as the Spanish-language newspapers El Latino, Noticias Libres, El Amigo, La Voz, and others, as well as radio stations in Spanish and the local Univision Spanish-language television network.

Latinos, in aggregate, exhibit low achievement and graduation rates. Insufficient educational resources for the more than 24,000 Latino children who had limited English proficiency (LEP) in the 2006–07 school year led to performance levels below those of other children. One facet of Latino culture is that children are taught not to speak unless spoken to, and this seems to put these children at odds with the traditional American classroom environment that stresses interaction with teachers.

Many Latino parents rebuff the value of education, either for economic reasons or because they have concluded that education will take too long to help their children get ahead financially. Although Latinos acquire more English with each successive generation, most children to date are bilingual and continue to learn and use Spanish at home.

Cultural Acceptance

Latino workers were welcomed, and in most instances, many towns work to facilitate the transition of these newcomers through the hiring of bilingual employees and by posting signs and instructions also in Spanish. Racial problems are scarce, but labor and housing discrimination has been reported. Allegations of racial profiling occur occasionally. In 2001, Latino residents of Rogers filed a class-action lawsuit against the city and the police department for violations under the Fourth Amendment, claiming that they were unlawfully targeted for stops, searches, and investigations in the form of racial profiling. The case was settled in 2003 when the Rogers police department agreed to conduct racial sensitivity training for its officers, refrain from enforcing federal immigration laws, track racial-profiling incidents, and create an advisory board to review the progress of these actions.

The immigration issue has been used by radicals to negate the contributions of this community, but several attempts by legislators to approve bills that reduce or negate civil rights to Latino immigrants failed in the Arkansas General Assembly during its 2005 and 2007 sessions.

Immigration raids on factories and other businesses have forced many undocumented migrants to be clandestine or move to other states. A couple of raids in Arkansas in the early part of the twenty-first century attracted national attention. The first one occurred on July 24, 2006, when Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raided the Petit Jean poultry plant in Arkadelphia (Clark County) just before 7:30 a.m., arresting 119 workers and leaving about thirty children without parental custody. The second one occurred on August 23, 2006, when ICE agents arrested eleven workers at the Country Club of Little Rock. Many Latinos are afraid that their deportation may sever family ties with their children born in the United States.

There is evidence that some Latino students in Arkansas face significant bullying and harassment, particularly by African-American students. Operation Intercept, a four-year study by University of Arkansas at Little Rock sociology professor Terry Trevino-Richard, used questionnaires and focus groups to collect data from Latino students in the Little Rock School District (with the district’s cooperation) and found a pattern of racism and harassment toward Latino students among Black students and some staff members. Trevino-Richard said that results of the study were presented to district superintendents and administrators in 2010 and 2011, but the problems documented in the study reportedly continue within district schools.

Demographics

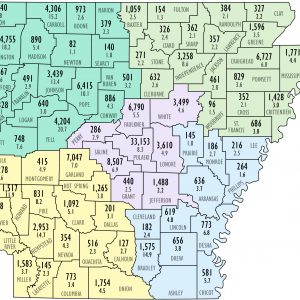

In 2005, Latinos surpassed African Americans to become the largest minority in the nation, and their pace of growth is greater than the white majority. The 2010 census found 50.5 million Latinos in the United States, or 16.3 percent of the population; by 2020, there were 62.1 million Latinos in the United States, or 18.7 percent of the population. In 2020, Latinos made up 8.5 percent of the population of Arkansas.

The Arkansas Latino population surged from 19,876 in 1990 to 186,050 in 2010 to 256,847 in 2020. Many Latino leaders believe that the official numbers fall short, comprising both documented and undocumented migrants. The Pew Center estimates that there were at least 40,000 undocumented migrants in Arkansas in 2006. A Winrock International survey estimated that fifty-one percent of all immigrants in Arkansas were undocumented. The Latino community continues to expand more rapidly than other ethnic groups, mainly due to new immigrants, a higher birth rate, lower adult mortality, and lower infant mortality rates.

In 2020, it was estimated that most of Arkansas’s 256,847 Latino residents lived in Benton County (19.6 percent of Arkansas’s Hispanic population) and Washington County (17.4 percent). Behind that were Pulaski County with 12.9 percent of Arkansas’s Latinos, Sebastian County with 7.5 percent, Garland County with 2.7 percent, and Sevier County with 2.1 percent. In 2020, Latinos made up 33,513 people in Pulaski County alone, or 8.3 percent of the county’s population.

According to a report published in 2013 by the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, children of immigrants—mostly Latino—made up ten percent of Arkansas children in 2010, versus five percent in 2000.

Future

The financial industry has recognized that Latino immigrants are a huge market and is seeking creative approaches to facilitate banking, money transfers, and homeownership. Lending institutions realize that Latinos demonstrate financial responsibility and are considering new ways to extend loans and mortgages, even without a credit history. Latino home ownership is increasing and may soon match the national ratio of almost seventy percent.

Community leaders estimate that fifty percent of Latinos in Arkansas are first generation, and a large percent are professionals or have a respected trade. Latinos have reached about eight percent of the general population in Arkansas and will continue to grow and be an important portion of the workforce. An important move in that direction came in 2021 when legislation was passed expanding rights for undocumented immigrants. Act 513 allowed college graduates who were recipients of the federal program Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) to receive teaching certificates in the state; Act 217 extended eligibility for the Arkansas Governor’s Scholars program to non-citizens; and Act 746 allowed state professional or occupational licensure for non-citizens.

Conclusion

To put pressure on Congress to pass an immigration bill that would normalize the status of an estimated 12 million undocumented Latinos in the United States, Latinos marched by the thousands during the spring of 2006 across the country. In Arkansas, the State Capitol Building was the site of demonstrations wherein thousands of Latinos gathered, prayed, and spoke for reform.

But divisions exist among Latinos in Arkansas, by national origin as well as by socio-economic and educational background. Assimilation to the American lifestyle and its advantages makes many decide to become citizens as they qualify, and the growing number of Latino children born in the United States continues to increase the number of Latinos who are U.S. citizens.

In 2024, Diana Gonzales Worthen of Springdale became the first Latino elected to the Arkansas General Assembly, from the first majority Latino district in the state.

For additional information:

Aragon-Blanton, Elizabeth Ann. “Voices from the Past: A Narrative Inquiry on the Schooling Experiences of Mexican-American Children in the Arkansas Valley, 1930–1950.” PhD diss., University of Colorado Colorado Springs, 2017.

Balderos, Ramon. “A Study of Latino Undergraduate Students in Retention Cohorts at the University of Arkansas.” EdD diss., University of Arkansas, 2023. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/5194/ (accessed February 21, 2024).

Berry, Harold. “The Use of Mexicans as Farm Laborers in the Delta.” Phillips County Historical Review 31 (Spring 1993): 2–10.

Bowman, Melany. “Home away from Home: The Assimilation of the Hispanic Population in Jonesboro, Arkansas.” PhD diss., Arkansas State University, 2011.

Broadwater, Lisa. “The Melting Pot Revisited.” Arkansas Times, May 4, 2001, pp. 10–12, 14–17.

Campos, Alejandra. “Ser Americano: The Cost of Being American.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2020. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3692/ (accessed December 1, 2023).

Donato, Rubén, and Jarrod Hanson. The Other American Dilemma: Schools, Mexicans, and the Nature of Jim Crow, 1912–1953. New York: State University of New York Press, 2021.

Echeverria, Wendy. “Inspirando el futuro: Stories about Latina Leaders in Northwest Arkansas.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2023. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/5019/ (accessed December 1, 2023).

El Latino. http://www.ellatinoarkansas.com (accessed July 7, 2021).

Escobar, Maria Andrea. “The Extent of Southern Hospitality: Hispanic Youths’ Sense of Belonging in El Nuevo South.” MA thesis, University of California, Merced, 2019. Online at https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6sj8v75j (accessed July 6, 2022).

Fitzpatrick, Kevin M., Wendie Choudary, Anne Kearney, and Bettina F. Piko. “Risk, Assets, and Negative Health Behaviors among Arkansas’ Hispanic Adolescents.” Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 35 (August 2013): 428–446.

Guerrero, Perla M. “Impacting Arkansas: Vietnamese and Cuban Refugees and Latina/o Immigrants, 1975–2005.” PhD diss., University of Southern California, 2010.

———. Nuevo South: Latinas/os, Asians, and the Remaking of Place. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017.

Hallett, Miranda Cady. “‘Better than White Trash’: Work Ethic, Latindad and Whiteness in Rural Arkansas.” Latino Studies 10 (Spring–Summer 2012): 81–106.

Hill, David. “In the Pit with the Fighting Roosters.” The Ringer, July 10, 2018. https://www.theringer.com/2018/7/10/17538780/cockfighting-ring-arkansas-ice-donald-trump (accessed July 7, 2021).

Hispanic Women’s Organization of Arkansas. http://www.hwoa.org/ (accessed July 7, 2021).

Kirk, John A., ed. Race and Ethnicity in Arkansas: New Perspectives. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Koon, David, and Rafael Nunez. “I Just Want Them to Stop…” Arkansas Times, September 19, 2012, pp. 14–18, 20. Online at http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/i-just-want-them-to-stop/Content?oid=2447943 (accessed July 7, 2021).

Leveritt, Mara. “Spanish Spoken Here.” Arkansas Times, September 29, 1994, pp. 14–17.

Lucas, Marietta Ann. “Bracero Labor in Northeast Arkansas.” Craighead County Historical Quarterly 6 (Summer 1968): 19–25.

Márquez, Cecilia. Making the Latino South: A History of Racial Formation. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2023.

Mitchell, Molly. “New Arkansas Laws Remove Barriers for Immigrants, Despite Legislature’s Rightward Turn.” Arkansas Times, June 30, 2021. https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2021/06/30/new-arkansas-laws-remove-barriers-for-immigrants-despite-legislatures-rightward-turn (accessed July 7, 2021).

Mont, Aíxa García. “The Impact of Latino Growth on Educational Institutions in Northwest Arkansas from 1990–2010: Two Decades of Change in Curriculum Design, Educational Resources and Services for Latino Students.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2015. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1079/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Morgan, James. “El Camino Latino.” Arkansas Times, November 6, 1998, pp. 12–15.

Smith, Jacqueline. “Listening to Voices of Latinx Immigrants in Rural America.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2021. https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/4303/ (accessed July 6, 2022).

Vrbin, Tess. “Hispanic Population Growing in State.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, January 9, 2022, pp. 1A, 8A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/jan/09/arkansas-hispanic-population-shows-steady-growth/ (accessed January 10, 2022).

Waren, Warren. “Social Capital and Hispanic Integration in Springdale, Arkansas: An Exploratory Study.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas, 2003.

Weise, Julie M. Corazón de Dixie: Mexicanos in the U.S. South Since 1910. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Michel Leidermann

El Latino

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.