calsfoundation@cals.org

Jacksonville (Pulaski County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 34°51’58″N 092°06’37″W |

| Elevation: | 285 feet |

| Area: | 28.65 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 29,477 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | September 6, 1941 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

2,474 |

14,488 |

19,832 |

27,589 |

29,101 |

29,916 |

|

2010 |

2020 | ||||||||

|

28,364 |

29,477 |

Jacksonville is located twelve miles northeast of Little Rock (Pulaski County) in the central part of the state. Little Rock Air Force Base (LRAFB) is located within the city limits of Jacksonville.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The first known settlers to move into the area were two Revolutionary War veterans, Jacob Gray Sr. and his brother Shared. The brothers had come from Williamson County, Tennessee, and settled in an area northeast of where the Daniels Ferry Road crossed Bayou Meto, about twelve miles northeast of Little Rock. Some of the men of the family with some of their slaves arrived the winter of 1820–21 and were followed by the rest of the family members and the remaining slaves by the spring of 1821. The group developed a thriving settlement and began planting crops and raising cotton for income.

By 1824, the U.S. Congress granted an appropriation to survey a road from Memphis, Tennessee, to Little Rock. The survey located the route to pass by the Gray settlement in Pulaski County and join the Daniels Ferry Road above Bayou Meto. Samson Gray, son of Jacob Gray Jr., who had become the head of the settlement, contracted to build the road from the Bayou of the Two Prairies to Little Rock and to build bridges across the Bayou of the Two Prairies and Bayou Meto. By 1827, the settlement had become a frequent stop for travelers, and by 1832, Samson was also running a mail stage to Arkansas Post (Arkansas County).

Following the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Memphis to Little Rock Road became a main travel route for removal of Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Cherokee, and many of the removal parties passed by the Gray settlement, where Samson Gray supplied them with rations. During the 1830s, other settlers, such as Reddrick Eason and Pleasant McCraw, moved to the area and settled near the road east of the Gray settlement. Eason and McCraw were also slave holders and suppliers to removal parties of Indians. The McCraw Cemetery is a remnant of this wave of settlement.

At the July 1838 term of the Pulaski County court, Thomas W. Gray, brother of Samson Gray, filed a petition to build a toll bridge across Bayou Meto to replace the original bridge. Gray sold the charter to John H. Reed in October 1838. Reed completed the bridge in 1839. After this time, the bridge became known as Reed’s Bridge.

Civil War through Reconstruction

Settlers continued to move into the area, which by this time was called Gray Township. Many were slave owners who raised cotton and corn. In August 1863, Union troops advanced along the Memphis to Little Rock Road from Brownsville (Lonoke County) toward Little Rock. On August 27, 1863, at the Action at Bayou Meto (a.k.a. Action at Reed’s Bridge), Confederate troops were forced to retreat toward Little Rock across Reed’s Bridge, which they burned during their retreat.

Surveys had been done for the Cairo and Fulton Railroad before the Civil War, but little had been accomplished. Nicholas Jackson moved to Gray Township following the war and began to buy up land along the proposed railroad right of way. On June 29, 1870, Jackson sold a choice piece of land to the Cairo and Fulton Railroad under the condition that the railroad company establish a depot in the section adjacent to Jackson’s land. Jackson then had a town site platted and, at first, called the town Jackson. The first train over the Cairo and Fulton Railroad from Argenta (Pulaski County) to Jackson Springs, as it was then called, ran on June 3, 1871. In another plat filed in 1872, Jackson called the town Jacksonville.

The building of the railroad was a wild time for Jacksonville, and saloons and a few businesses sprang up. The construction brought needed work for both the African-American and white populations. The post office was established on August 7, 1871, and Jackson was the first postmaster.

Robert Beall and his wife, Sophia McBride Beall, both former slaves, had acreage in the Jacksonville area by 1870, and most of the black population settled around their home. A black Baptist church was in place in 1870.

Post Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

In January 1876, Robert and Sophia Beall donated an acre of land to the Mt. Pisgah Baptist Church. The church served as a school and worship center for the black population for many years.

In 1880, Jackson donated six lots on Oak Street to the Jacksonville Academy Association. A school was built on the lots in 1881. The first school for the white children was a one-room log building that housed all eight grades. The log building was replaced in 1897.

During this time period, Jacksonville served as a center for the large surrounding agricultural area. Excursion trains ran to the depot. Farmers hauled their crops to the railroad for shipment. The town had a general store, a flour mill and gin, a grocer, various law and medical offices, Baptist and Methodist churches, and a hotel.

Early Twentieth Century

On May 18, 1907, the Jacksonville Special School District was formed. On July 16, 1927, the Jacksonville school system was consolidated with the unincorporated areas of Pulaski County and named the Pulaski County Special School District (PCSSD). In 1920–21, a Rosenwald school was built next to the Mt. Pisgah Baptist Church for the black children.

In 1910, the black citizens of Jacksonville organized a chapter of the fraternal organization Supreme Royal Circle of Friends of the World. The Jacksonville group was named Forward March Circle No. 314. The Jacksonville circle built a two-story lodge building that was the social center for most of the black population for many years.

The Great Depression did not hit Jacksonville as hard as it did some parts of the country. Most of the people lived on farms and had crops to help them get along. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) established Camp No. 3787 in Jacksonville; the construction began on May 5, 1935. The enrollees began arriving in July, and by September, the company consisted of 200 men. During operations, the men at the camp built stock dams, planted trees, cleared pasture land for farming, planted cover foliage to control erosion, and performed many other conservation activities.

World War II through the Faubus Era

In 1941, Jacksonville’s population was about 400. No natural gas, street lights, or water and sewer system existed. There was a telephone switchboard, and electricity was provided to stores and homes from a branch line of the Arkansas Power and Light (AP&L) company. Governor Homer Martin Adkins, who led the state during the war years, hailed from Jacksonville.

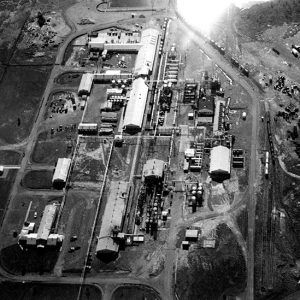

On June 5, 1941, the Arkansas Gazette carried the news that a fuse and detonator plant, called the Arkansas Ordnance Plant (AOP), was to be built in Jacksonville. The land near Jacksonville was taken over by the government by condemnation proceedings, and Jacksonville became a boom town. Housing was in very limited supply, and people lived wherever they could, even in their cars, until a trailer park and housing addition were built. The AOP stayed in production from 1942 to 1945.

To deal with the changes the AOP was to bring, Jacksonville incorporated on September 6, 1941, and elected John H. Bailey as the first mayor. The first action of the new town officials was to seek a sewer and water system.

After the AOP closed in 1945, businesses bought and leased several of the AOP buildings, and Jacksonville began to develop a more industrially based economy. The Arkansas Association for Crippled Children opened the Children’s Convalescent Center in the former AOP hospital building on November 10, 1947. The children’s center was the only center of its kind in Arkansas. The Children’s Convalescent Center later moved to Little Rock and was the forerunner of Arkansas Children’s Hospital.

The first bank, the Jacksonville State Bank, was organized in 1949. Founding member Kenneth Pat Wilson was president of the bank for many years. Wilson and other citizens of Pulaski County in 1951 began to approach the U.S. Air Force to locate an air base in central Arkansas. The citizens of Pulaski County raised funds and purchased the land near Jacksonville to donate for the Little Rock Air Force Base, which was activated on October 9, 1955.

In 1951, the Mt. Pisgah Baptist Church moved to another part of Jacksonville, and the school for the black children closed. The PCSSD then bused the black students to schools in the McAlmont area of the county. This arrangement was continued until about 1966, when PCSSD adopted the “Freedom of Choice Plan,” which allowed students to go to the school of their choice. Few, if any, of Jacksonville’s black parents enrolled their children in the Jacksonville schools. Most of the parents felt their children would not be accepted in the “white Jacksonville schools.” Segregated school buses still made the trip from Jacksonville to McAlmont until the 1969–70 school year, when the PCSSD school board announced that any student who lived within two miles of a school could not ride the bus or be bused to another school of their choice.

After the closure of the McAlmont junior and senior high schools in 1971, many black students and teachers were reassigned to Jacksonville schools. Elementary schools were soon desegregated. In 2014, residents of Jacksonville and northern Pulaski County approved a proposal to detach from the PCSSD to form a new district.

Modern Era

In January 1962, Rebsamen Memorial Hospital opened its doors with thirty beds and seventeen employees. Over the years, the hospital has grown, and the name was changed to Rebsamen Regional Medical Center. The hospital is a 113-bed acute care facility with over 500 employees and 200 physicians on staff. In 2008, the hospital became the North Metro Medical Center; it closed its emergency department in August 2019, leaving the city without emergency room facilities.

Pathfinder, Inc., was incorporated on August 26, 1971, and licensed by the Arkansas Mental Retardation Developmental Disabilities Services. It is now a statewide program with twenty-eight locations around the state, employing 500 people in the Jacksonville area and 900 statewide. Pathfinder provides services to adults and pre-school children with developmental disabilities.

In 1948, the Reasor Hill Company purchased the Artillery Booster Line No. 1, a 200-acre area that had been part of the AOP, and began producing insecticides. In 1962, the plant was sold to Hercules Powder Company (later Hercules Inc.). Hercules continued to make insecticides and also produced Agent Orange. Dioxin, a toxic byproduct of the Hercules production, accumulated in waste on the site. From 1971 to 1976, Transval leased the site from Hercules and continued production methods with dioxin as a part of the waste. In 1976, Transval was reorganized into Vertac, Inc., and the same products were produced, along with dioxin-contaminated wastes.

In 1978, the National Dioxin Survey found high concentrations of dioxin in the waste sludge and dioxin contamination in wildlife and fish as far as fifty miles downstream. In 1979, an investigation of practices at the plant was launched. Some efforts were made by Vertac to improve its handling of waste, but in 1983, because of extensive contamination, the site was declared a Superfund site. It was described as one of the worst dioxin-contaminated sites in the nation. Vertac continued to make some improvements on the handling of the toxic waste but, in 1987, the company abandoned the site, leaving approximately 29,000 drums of dioxin-containing wastes.

In 1987, the Arkansas Department of Pollution Control and Ecology (ADPCE) conducted remedial activities, including the operation of a rotary kiln to destroy the drummed wastes. Operations of the kiln started in January 1992. In June 1993, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) assumed responsibility of clean-up and operated the kiln until September 1994. During the operation of the kiln, 9,804 tons of waste were destroyed on site, and another 1,200 tons of waste were destroyed off site. The remediation using the incineration process cost approximately $31.7 million. The courts held Hercules and Vertac responsible for clean-up operations. The site remains closed to the public in 2007 and is monitored by the EPA but no longer constitutes any danger to the public.

Following the close of the AOP, Jacksonville’s population dropped to 2,474 in 1950. The coming of LRAFB again brought a population spurt, and the population has generally increased since that time. Although many Jacksonville residents travel to Little Rock for work, there are many opportunities for employment in Jacksonville and on LRAFB. A new city hall and community center were built in the 1990s.

A March 31, 2023, tornado cut a three-mile path through Jacksonville, damaging a large portion of the city.

Attractions and Notable People

The Jacksonville Museum of Military History is open six days a week and has displays concerning military heritage. The Reed Bridge Civil War Battlefield is open to the public. LRAFB holds air shows every two years to entertain and demonstrate the air force’s capabilities. The Jacksonville Wing Ding Festival is held each year in October.

Local legislator Mike Wilson represented Jacksonville and, after his political career, led a legal campaign that brought down the General Improvement Fund scheme. Newspaperman Garrick Feldman founded, edited, and published the Leader.

For additional information:

Jacksonville Chamber of Commerce. http://www.jacksonville-arkansas.com/ (accessed March 31, 2023).

Little, Carolyn Yancey, ed. Siftings from Jacksonville’s History, 1820–1980. N.p.: 1986.

Little, Carolyn, et al. The History of Jacksonville, 1818–1976. Little Rock: Target Printing, 1976.

Carolyn Yancey Kent

Jacksonville, Arkansas

I am the daughter of Wayne H. Jackson, deceased. Wayne Jackson was the last grandson of Nicholas Jackson; he has one son, Richard (Rick) Martin Jackson of Las Cruces, New Mexico, who is the closest living male heir. I am the youngest of Wayne’s three daughters and live closest to Jacksonville. Rick was a soldier in the U.S. Army, stationed in Germany and then returned to service as a civilian for reconstruction purposes in the Middle East. He is a business owner and has been Man of the Year several times both in his own state and in the nation. He is a small business owner and has spoken before the U.S. Congress on the concerns of the small business men and women of today. Our father owned several businesses in Carnegie, Oklahoma, and aided many others behind the scenes in their own businesses. He was well thought of and was a staunch supporter of the Methodist Church, where he was a deacon, a Sunday School teacher, an administrator, and a Mason. He and my mother were married for over sixty-five years. She was an Eastern Star and the Rainbow Girls’ Mother Adviser. I have never had more pride in my heritage of being an heir to Nicholas Jackson than I have today.