calsfoundation@cals.org

Henry Miller Shreve (1785–1851)

Henry Miller Shreve was a steamboat captain and inventor who is noted for performing much-needed clearance work on America’s major river systems during the first half of the nineteenth century. This work included using his own specially designed snag boat to clear large obstructions from the Arkansas River between Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) and Little Rock (Pulaski County), greatly aiding steamboat travel and trade in the state of Arkansas.

Henry Shreve was born on October 21, 1785, in Burlington County, New Jersey, to Isaiah Shreve and his second wife, Mary Cokely. He had four half-siblings from his father’s first marriage to Grace Curtis. Henry, the fifth child born to Isaiah and Mary, was barely three when, in 1788, his father moved the family to Brownsville in western Pennsylvania, where Henry’s oldest brother, John, had recently taken up residence.

Shreve spent his youth in the area between the Youghiogheny and Monongahela rivers and knew he wanted to spend his life on the water by the time he was fourteen. He bought his first keelboat in 1807 and began a lucrative fur trade between St. Louis, Missouri, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In 1810, he set out for the lead mines run by the Sauk and Fox Indians on the Galena River. The first American to pilot a keelboat so far up the Mississippi River system, Shreve struck a deal with the Indians and carried lead from the mines to New Orleans. Shreve married Mary Blair in 1811, and they had three children. The young husband was also married to the waters, however, and Mary spent a great deal of time raising their children alone.

Shreve watched with interest as the Fulton-Livingston group inaugurated steamboat trade on the Mississippi. He soon became convinced that the design of Fulton’s boat would not work well, since the Mississippi and other western rivers were much shallower than those in the eastern part of the United States. Fulton’s design simply sat too deep in these shallow waters, and his boats frequently ran aground, with sometimes tragic results. Determined to do better, Shreve invested in a steamboat designed for inland rivers. His boat had a flatter bottom and a wider girth, which allowed even a relatively large vessel to perform better than the Fulton design. Shreve’s first boat designed in the new style was The Enterprise. This new steamboat made its inaugural voyage to New Orleans in 1814, where Shreve assisted Andrew Jackson in the city’s defense during the War of 1812. His success encouraged him to design a steamboat even better adapted to the Mississippi. The Washington had an even lower, shallower hull, two decks, and twin smokestacks, a design that became the standard on inland waters. Perhaps the success of Shreve’s design, when compared to the problems of Fulton’s steamboats outside eastern rivers, contributed to Shreve’s success when he mounted a legal challenge to the Fulton-Livingston monopoly on government contracts for shipping on the lower Mississippi in Louisiana.

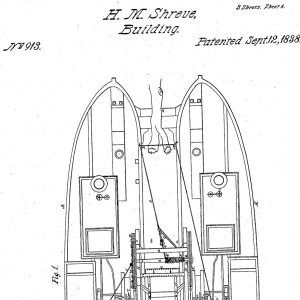

On January 2, 1827, Shreve was named Superintendent of Western River Improvements, and he began clearing obstructions from the Mississippi and Ohio rivers by 1829. The Heliopolis, a steam snag boat of his own design, was actually constructed of twin 125-foot hulls connected by a series of beams and fitted with numerous contraptions for either ramming embedded trees or hoisting snags directly from the riverbed. It even had a sawmill on board to dispose of trees when necessary.

Shreve also cleared the Arkansas River of obstructions in the early 1830s. Like other inland rivers, the Arkansas was subject to “cave-ins,” as the natives called these periodic events. During spring rains, runoff from fields into the rivers caused large chunks of soil along the riverbanks to fall into the streams, carrying saplings and even large trees along. Over time, this resulted in logjams that made navigation difficult, if not impossible. A congressional act in 1832 designated $15,000 for work on the Arkansas, noting that “snag boats” would be necessary to clear out the debris.

Shreve supplied two snag boats, three machine boats, and a steamboat. He made it from Pine Bluff to Little Rock by February 22, 1834, and then did additional clearing above the capital city. In all, workers cleared 4,907 obstructions from the Arkansas. (By some accounts, this averaged one snag every eighty-eight yards.) His work on the Arkansas River contributed to the success of steamboat travel and trade in the state of Arkansas, as that body of water became effectively tied to the country’s main transportation artery, the mighty Mississippi.

Shreve’s battle with the Great Red River Raft in Louisiana brought him the greatest renown. “The Raft” was a logjam on the Red River between Baton Rouge and present-day Shreveport. Created by the frequent “cave-ins” common to these western rivers, the Raft made navigation by steamboats on the Red River impossible, thus hindering trade in an otherwise inviting area. Beginning in 1833, Shreve labored to clear almost 200 miles of obstructions that had made the Red difficult to navigate for hundreds of years. The work was difficult, and the raft was so solid in places that new trees grew from the driftwood that accumulated in the middle of the riverbed. A congressional report later described this work: “One snag raised by the Heliopolis… contained 1600 cubic feet of timber, and could not have weighed less than sixty tons.”

Shreve was working on the Raft in northern Louisiana in 1836 when local entrepreneurs incorporated a new town on the banks of the now free-flowing Red. They named the town Shreveport in gratitude for his efforts in clearing the Raft.

Shreve remained superintendent until 1841, when he was relieved of his appointed office by the new Whig administration. At the end of his term, he was in charge of five snag boats, the last of which was named the Henry M. Shreve. Shreve moved to St. Louis, where he farmed and repeatedly, if futilely, petitioned the federal government for compensation for his invention of the snag boat. Despite the findings of various committees that his work had saved the government hundreds of thousands of dollars, Congress never appropriated adequate compensation for Shreve, and he died without having reached agreement with the government.

Shreve’s wife Mary died in 1845, and in 1847, he married Lydia Rodgers, who had served as his housekeeper. The couple had two daughters. His youngest child, Florence, was born in 1849 and died in January 1851. Shreve was heartbroken by the death of “Our Little Florie,” and some suggest that her death aggravated his own poor health. The Shreves also lost two grandchildren during that winter. Shreve died on March 6, 1851, after a severe St. Louis winter that had dragged him down. His death took place during a period when St. Louis was experiencing a return of the “dread fevers,” which may have been a cholera outbreak. He is buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery in St. Louis, overlooking the Mississippi River, a burial site that is exceptionally fitting.

As testament to his importance to river navigation in America, Henry Miller Shreve in 1986 became one of the first inductees into the National River Hall of Fame in Dubuque, Iowa, along with Samuel “Mark Twain” Clemens. The Hall of Fame has rightly described Shreve as “a giant among America’s river men and women.” This is an appropriate tribute to a man who dedicated his life to the country’s greatest waterways—the Mississippi, the Ohio, and the Arkansas.

For additional information:

Gudmestad, Robert. “Steamboats and the Removal of the Red River Raft.” Louisiana History 52 (Fall 2011): 389–416.

Henry Miller Shreve Letters, 1827–1841. Archives and Special Collections. Louisiana State University at Shreveport, Shreveport, Louisiana.

McCall, Edith. Conquering the Rivers: Henry Miller Shreve and the Navigation of America’s Inland Waterways. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1984

———. Mississippi Riverboatman: The Story of Henry Miller Shreve. New York: Walker and Company, 1986.

Pfaff, Caroline S. “Henry Miller Shreve: A Biography.” Louisiana Historical Quarterly 10(April 1927): 192–240

Janet G. Brantley

Fouke, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.