calsfoundation@cals.org

Essex Pippin (Execution of)

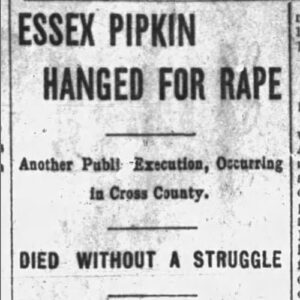

Essex Pippin (sometimes listed as Pipkin), a nineteen-year-old African American man, was hanged at Vanndale (Cross County) on October 11, 1901, after being convicted of raping two women.

On July 29, 1901, a man reportedly raped a Black woman named Leah Wooden and then attacked Mrs. Allen Taylor, described in contemporaneous newspaper accounts as “a respectable white woman, who is the wife of a prominent farmer living near Wynne” in Cross County. Essex Pippin, who lived about a quarter mile from Vanndale, was soon arrested and rushed to the state penitentiary in Little Rock (Pulaski County) by local lawmen to protect him from “lynching at the hands of a rapidly forming excited populace,” providing “a narrow escape from death by the rope or stake route.”

Pippin was returned to Cross County in late August, and there a judge had empaneled a special grand jury who took less than an hour to charge him with two counts of criminal assault. A trial jury was then seated, which heard from six witnesses, including the two victims. Pippin alone testified in his defense; he was found guilty on August 27, 1901, and sentenced to hang at Vanndale on October 11.

The execution would be public because the Arkansas General Assembly, reacting to John Wesley’s sensational rape trial in Arkadelphia (Clark County) earlier that year, had removed limitations on the number of witnesses at hangings, with the view that “executions of rapists [are] an object-lesson, therefore the barrier should be removed.”

On October 11, Pippin was taken from the jail at Paragould (Greene County) at 4:00 a.m., reaching Vanndale by train at around 6:00 a.m. The Arkansas Democrat reported that “he said he did not fear the final event, and intimated that he had about as soon die upon the gallows as go to the penitentiary for life.”

At the execution site, Pippin climbed the steps of the scaffold “without a tremor” as two preachers accompanying him gave speeches to the crowd and sang, “Death Is Only a Dream.” The doomed man addressed the audience, saying, “I stand before you in the shadow of death and advise you to be careful in this world of trouble. God forgive me, I am not afraid to leave. I am going home to rest happy.” The sheriff then opened the trap door, and Pippin dropped to his death.

While 2,000 people had attended Wesley’s hanging in Arkadelphia, and a mob of 10,000 watched Charles Anderson hang for rape in Little Rock, there is no mention in the press of the number of people who attended Pippin’s execution beyond noting that “the hanging was public, in accordance with the…law” and “several parties from out of town witnessed the execution.”

In addition to Wesley, Anderson, and Pippin, two other Black men—Hal Mahone and Elisha Davis—would be executed in public after being convicted of rape in the first years of the twentieth century. The public execution exception for rape convictions was rescinded in 1905.

For additional information:

“Brought Here for Safety.” Arkansas Gazette, July 31, 1901, p. 3.

“Essex Pipkin Hanged for Rape.” Arkansas Gazette, October 12, 1901, p. 1.

“Essex Pippin Must Hang.” Arkansas Gazette, August 30, 1901, p. 6.

“Paid Penalty.” Arkansas Democrat, October 11, 1901, p. 1.

“Pippin Must Hang.” Arkansas Democrat, August 30, 1901, p. 8.

Mark K. Christ

Central Arkansas Library System

Capital Punishment

Capital Punishment Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Law

Law Essex Pipkin Execution Article

Essex Pipkin Execution Article

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.