calsfoundation@cals.org

John Wesley (Execution of)

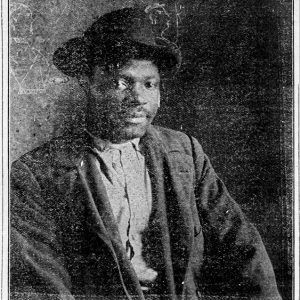

John Wesley, an African American man, was hanged at Arkadelphia (Clark County) on March 23, 1901, for raping a young white woman the previous year. The public furor around Wesley’s crime led the Arkansas General Assembly to make executions of rapists public instead of limiting the audience to twenty-five people.

Josie Cleveland, aged seventeen, worked as a telephone operator in Arkadelphia. After her shift ended on December 3, 1900, she was walking home when a Black man grabbed her as she was passing a cemetery and dragged her into the graveyard. There, for “nearly two hours….She fought like a tigress, though the negro choked her horribly and lacerated her flesh considerably.” Her father, “having become alarmed at the lateness of his daughter,” went looking for her. He noticed that the cemetery gate was open, and as he went to close it saw a man jump up and run. Hearing a “scream of terror,” he found his daughter and carried her home.

As the search for the rapist began, several “negro suspects [were] arrested and taken before Miss Cleveland for identification, but she has failed to fasten guilt upon any one of them.” After several weeks, deputy marshal W. B. White of Malvern (Hot Spring County) developed John Wesley, aged twenty-eight, as a suspect, and Clark County Sheriff J. H. Abrahams arrested him in Ogemaw (Ouachita County) on December 28, 1900. White would receive $1,700 in reward money for identifying Wesley as the suspect.

Wesley was taken to Arkadelphia, where Josie Cleveland identified him as the man who had raped her; however, local officials did not reveal that information, and the Arkansas Gazette and Arkansas Democrat reported that she had failed to identify him as her attacker and that Wesley was freed.

Reportedly, the information about Cleveland’s identification of Wesley was not made public until Wesley was arraigned on the rape charge because “it is the desire of the authorities that the law be allowed to take its course,” and there was a strong possibility that Wesley would be lynched because of widespread outrage over the attack. At Wesley’s February 8, 1901, arraignment, Cleveland testified that “if it was left to her there would be no necessity for a trial—she could shoot his heart out.” As public outrage continued to seethe, the accused rapist was “guarded day and night by Sheriff Abrahams in person.” Anger increased as a Mrs. W. P. Bullard and a Mrs. Graves identified Wesley as the man who had raped them in Malvern in 1898.

Wesley’s trial began on February 18, 1901, and “the court-room was packed and jammed and several hundred people were on the outside.” Abrahams was permitted to open the proceedings with a prayer “that no act should be done that would cause regret or would be a blot on the fair name of Clark county,” which a Democrat correspondent deemed “very appropriate.”

Cleveland testified that Wesley was the man who raped her, and Abrahams told jurors “he had carried about one hundred negroes before Miss Cleveland since December 3” before she identified Wesley as her attacker. The defendant testified that he was having dinner in Arkadelphia with friends when the assault occurred, but an Arkansas Gazette reporter noted that “he attempted to prove an alibi, but it was a signal failure.” The jury only took twenty-five minutes to return with a guilty verdict, and Wesley “was carried to the jail…under heavy guard,” while sentencing was postponed until “the crowds disperse and the feverish condition of the public abates.” A judge on February 21 formally sentenced him to hang on March 23. The Arkansas Supreme Court affirmed the sentence on March 12.

Recognizing concerns that local citizens might take the law into their own hands after a crowd in Gurdon (Clark County) burned Wesley in effigy, about which the Arkansas Democrat stated “no good will come of such acts,” state Representative S. P. Meador of Clark County entered a bill before the state legislature on March 7, 1901, “providing for public hangings of convicted rapists” and set a path for “early passage in order that it may become a law in time” for Wesley’s execution. The bill was passed on March 20, and Governor Jeff Davis signed it into law the next day. The Democrat predicted that the hanging “will be witnessed by thousands from all over Clark and surrounding counties” and noted that previous law would have allowed only a small number of witnesses, “but the fiendishness of Wesley’s crime so inflamed the people…that they demanded that the execution be made public.”

Before his execution, Wesley made a formal confession to Sheriff Abrahams, saying, “I’m guilty in all three cases, and I’m glad that the people have let me live long enough to make peace with God. I’ve got religion and I believe God has forgiven me. I am ready to die.”

It was raining heavily on the morning of March 23, 1901, as carpenters removed the stockade surrounding the gallows at the Clark County jail, and around 2,000 people, “white and black, old and young, male and female, students and children in arms,” gathered to watch Wesley hang. Abrahams escorted the condemned man to the scaffold as Wesley walked steadily, while carefully avoiding stepping in rain puddles. A Gazette correspondent wrote that “he bore up with wonderful nerve until the black cap was over his face, when began to slowly sway as he chanted, ‘Lord, have mercy on my soul.’” The sheriff opened the trap door at precisely 10:00 a.m., and “the body of John Wesley shot downward, and as he fell a great cheer went up from the assembled crowd.”

The seven-foot fall failed to break his neck, and “in his death agonies he began to twist and, reaching up with his shackled hands, caught the noose and lifted himself fully three feet.” An Arkadelphia newspaper wrote that the crowd “with cries of joy, saw his prolonged death struggles as he expiated his heinous crime.” After seventeen minutes, he was declared dead, and his body was sent to family in Palestine, Texas, for burial.

The day after Wesley’s hanging, the Pine Bluff Daily Graphic editorialized that the legislation making his execution public “was nothing less than compromise with the mob element,” concluding that “that body was not governed by the demands of justice…but was swayed by the passions of the frenzied populace of Arkadelphia…the passions of people, who, no doubt, now that the execution is over…will reach the early conclusion that society has not been in any degree more thoroughly avenged, but that the finer feelings of decency have been shocked.”

Four other Black men—Charles Anderson, Essex Pippin (or Pipkin), Hall (or Hal) Mahone, and Elisha Davis—would also be executed in public after being convicted of rape. The public execution exception for rape convictions was rescinded in 1905.

For additional information:

“Arkadelphia Fiend.” Arkansas Gazette, December 29, 1900, p. 2.

Arkansas Democrat, February 16, 1901, p. 4, col. 3.

Arkansas Democrat, March 5, 1901, p. 4, col. 1.

“Arkansas News.” Arkansas Democrat, January 1, 1901, p. 6.

“At the State House.” Arkansas Democrat, March 21, 1901, p. 4.

“Compromise with Lawlessness.” Pine Bluff Daily Graphic, March 24, 1901, p. 4.

“Evidence In.” Arkansas Gazette, February 19, 1901, p. 1.

“His Third Victim.” Nashville [Arkansas] News, February 16, 1901, p. 1.

“A Just Reward.” Southern Standard, March 28, 1901, p. 2.

“Legislative Notes.” Arkansas Gazette, March 8, 1901, p. 6.

“New Trial Refused.” Arkansas Gazette, March 14, 1901, p. 2.

“Not Caught Yet.” Arkansas Gazette, December 5, 1900, p. 2.

“Not the Guilty Man.” Arkansas Gazette, December 30, 1900, p. 1.

“Second Day.” Arkansas Democrat, February 19, 1901, p. 1.

“State News Notes.” Arkansas Democrat, December 4, 1900, p. 2.

“To Hang March 23.” Arkansas Democrat, February 22, 1901, p. 1.

“To See Hanging.” Arkansas Democrat, March 22, 1901, p. 7.

Trotti, Michael Ayers. The End of Public Execution: Race, Religion and Punishment in the American South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022.

“Verdict of Guilty.” Arkansas Democrat, February 19, 1901, p. 1.

“Wesley Confesses for the First Time to Three Assaults,” Arkansas Democrat, March 23, 1901, p. 1.

“Wesley Convicted.” Arkansas Gazette, February 20, 1901, p. 2.

“Wesley Is the Man.” Arkansas Gazette, February 9, 1901, p. 1.

“Wesley Met Fate Without a Tremor.” Arkansas Gazette, March 24, 1901, p. 1.

“Wesley Trial.” Arkansas Democrat, February 18, 1901, p. 1.

“Wesley Underguard [sic].” Arkansas Democrat, February 13, 1901, p. 3.

“World’s Fair Bill Passes the Senate.” Arkansas Gazette, March 21, 1901, p. 3.

Mark K. Christ

Central Arkansas Library System

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940

Early Twentieth Century, 1901 through 1940 Law

Law John Wesley Indictment

John Wesley Indictment  John Wesley Execution Story

John Wesley Execution Story  John Wesley Execution Story

John Wesley Execution Story

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.