calsfoundation@cals.org

Elmer Wayne Mikel (1905–1988)

Elmer Wayne Mikel was a bootlegger during Prohibition and later became a self-published author who wrote books and essays about his criminal life and his experiences at the notorious Tucker State Prison Farm (now the Tucker Unit of the Arkansas Department of Correction) in Jefferson County in the 1930s. Mikel was also a songwriter who wrote about Arkansas subjects, including the deadly Greenwood (Sebastian County) tornado of 1968.

Elmer Mikel was born on October 8, 1905, in Jenny Lind (Sebastian County), one of ten children of George Elmer Mikel and Amanda Featherston Mikel. George Mikel, a Missouri native, was active in the United Mine Workers of America and ran as a socialist candidate for governor of Arkansas in 1912. Elmer Mikel attended high school but never graduated. He later wrote that Jenny Lind had “no law” and that, as young man, “all he ever saw or heard about was violence.”

Rather than follow his father or brother Lyman Mikel (who became a state senator from Sebastian County) into politics, he became a bootlegger. In 1923, the same year he married Marsha Dodson, with whom he had three children (William, Wanda, and Wayne), he began manufacturing and selling illegal liquor in Oklahoma, not far from Fort Smith (Sebastian County). While bootlegging, Mikel claimed to have met criminals Ma Barker, Pearl Starr (bordello owner and daughter of the outlaw Belle Starr), and Clyde Barrow (though, to his knowledge, he never met Bonnie Parker).

In January 1931, Mikel was arrested for bootlegging. He was sentenced to five years at the state penitentiary in Little Rock (Pulaski County), commonly known as “the Walls,” but he was released after nine months. Mikel went back to crime, committing a string of robberies. Mikel claimed to have helped notorious criminal Charles Arthur “Pretty Boy” Floyd rob a bank in Kansas. He also wrote of attending Floyd’s funeral in Oklahoma, for which tens of thousands of people turned out.

Mikel expanded his criminal activities to include stealing cars and cracking safes. In Little Rock, he was arrested again, this time for robbery. Mikel made bail, joined a gang, and soon was arrested yet again for burglary.

In the spring of 1933, Mikel was sent to Tucker State Prison Farm, where he would be held until late 1934. Mikel called Tucker a “hell hole,” but his time was not as horrific as it was for others. His political connections through his brother likely won him preferential treatment. Mikel worked in the identification office, where new inmates were finger-printed and photographed. The job freed him from brutal field work on the “long line.”

A bad infection almost cost him his leg, but Mikel recovered and was made a trusty (appointed prisoners who served as armed guards). He sometimes worked as a driver, which allowed him to visit the women’s prison at Jacksonville (Pulaski County), where he met Helen Spence, the “Shanty Boat Girl” famous for having shot her father’s killer in court. Although he was married, Mikel fell in love with Spence, whom he called his girlfriend.

Mikel was paroled in January 1935. He returned to his family and operated a tavern in Rogers (Benton County). In the 1940s, Mikel moved with his family to California. He wanted to enlist after the outbreak of World War II but was denied entry into the military because he was an ex-convict. He worked instead for the Consolidated Aircraft Company in San Diego during the war.

In 1968, at the height of the investigations and scandals surrounding conditions at Arkansas prisons, Mikel wrote to controversial superintendent Tom Murton and Governor Winthrop Rockefeller about the abuses he saw at Tucker prisoner in the 1930s. Mikel’s description of Tucker confirms the horrors described by other inmates, including inhumane living conditions, inedible food, whippings, shootings, and corruption within the prison. Mikel claimed that 1933 was an especially bad year, with the killing of prisoners being commonplace.

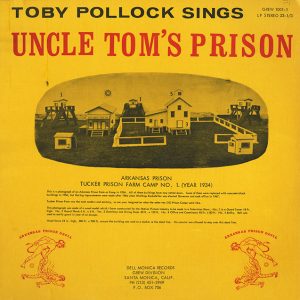

In 1970, Mikel wrote and self-published Uncle Tom’s Prison, which recounted his life as a criminal and prisoner, and issued an album of the same name with his musical collaborator Glenn R. Arters. Mikel’s songs were written in the American folk/protest style and sung by Toby Pollock.

In 1975, Mikel released “Jenny Lind,” a song about his hometown in Arkansas and “Greenwood Tornado,” a song about the destructive tornado of April 1968; both were sung by Lee Richards. The next year, in honor of the nation’s bicentennial, Mikel released the songs “Give Me Back My America” and “Is This My America.” A few years later, Mikel returned to Arkansas from California to work on a book about Bonnie and Clyde, writing the story in the same building where the pair had once recuperated from a car crash.

Mikel died on April 16, 1988, in Los Angeles, California.

For additional information:

Baskett, Thomas S., Jr. “Miners Stay Away! W. B. W. Heartsill and the Last Years of the Arkansas Knights of Labor, 1892–1896.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Summer 1983): 107–133.

Kiser, G. Gregory. “The Socialist Party in Arkansas, 1900–1912.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 40 (Summer 1981): 119–153.

Mikel, Elmer. “Bloody (Greasy) Mama.” Arkansas Small Manuscripts Collection. UALR Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas.

———. Famous Photographs of the Bonnie and Clyde That I Knew. Santa Monica, CA: Elmer Mikel, 1977.

———. “Pretty Boy Floyd or the Story of the Four Brothers.” Arkansas Small Manuscripts Collection. UALR Center for Arkansas History and Culture, Little Rock, Arkansas.

———. Uncle Tom’s Prison. Santa Monica, CA: E. Mikel, 1970.

Colin Edward Woodward

Center for Arkansas History and Culture

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.