calsfoundation@cals.org

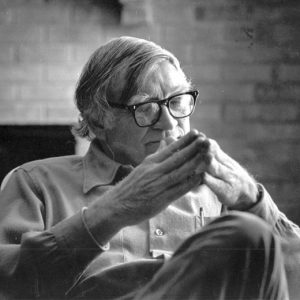

Dee Brown (1908–2002)

aka: Dorris Alexander Brown

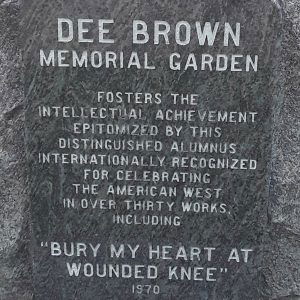

Dorris Alexander (Dee) Brown is the only contributor to Arkansas literature included in The New York Public Library’s Books of the Century (1996), a selection of the “most significant works of the past 100 years.” He lived more than half his life in Arkansas and, beginning as a teenager, wrote continuously for publication, often long into the night, as he did for his best-known work, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (1970), which changed the way the world thinks about America’s westward expansion. His daytime profession as a librarian was the key to his international success as a writer: he knew how to find primary sources, such as Indian Treaties written in their own Native American words. His most famous bestseller has the rare distinction among historians of being considered an indispensable reference for Native American studies.

Dee Brown was born in a logging camp in Alberta, Louisiana, on February 29, 1908. His father, Daniel Alexander Brown, died when Dee was five years old. Soon afterward, Brown moved with his mother, Lulu (Cranford) Brown, his brother, and his two sisters to the Arkansas town of Stephens (Ouachita County). His mother became postmaster of the town. The family lived with Brown’s maternal grandmother, whose father had known Davy Crockett. She told stories to her grandson about the famous frontiersman and how her family survived the Civil War in Arkansas.

Stephens was a typical small Arkansas town until oil was struck in the 1920s, bringing in many investors. In 1924, the family moved to Little Rock (Pulaski County), where Brown attended high school. When he was about fifteen years old and a student at Little Rock High School, Brown and some friends published a neighborhood tabloid, The Live Wire, to expose the oil “flimflammers” in Stephens. Brown admired a Native American baseball player for the Arkansas Travelers. Having learned from Native American playmates in Stephens to cheer for the Indian “villains” portrayed in western movies of the time, it was natural for Brown to admire a Native American baseball player. The player sympathized with Brown and his friends, who could not afford tickets to the games, and routinely threw baseballs to the boys, which allowed them entry to the games.

After graduating from high school in 1927, Brown got a job as a printer for the Harrison Daily Times in Boone County and became a fledging journalist. His first story covered a tornado that struck Green Forest (Carroll County). During this time, Brown was falsely accused of robbing a bank in Jasper (Newton County). He spent the night in the Newton County Jail and, the next day, discovered that the tires to his borrowed Model T had been stolen by the man who had falsely accused him.

In 1928, realizing that he did not know enough to be a reporter, Brown went to Arkansas State Teachers College (ASTC), now the University of Central Arkansas (UCA), in Conway (Faulkner County), graduating in 1931 with a Bachelor of Arts and Education degree with a major in history. His mother ran a boarding house for ASTC students, and his long career as a professional librarian began in Conway, working in the college library, where he was thrilled to be able “to get hold of almost any book he wanted.” ASTC history professor Dean McBrien set him on the course he was to take as a writer. McBrien took Brown on two summer trips out West, during which Brown wrote that he “learned far more than any classroom could offer….He converted me into a fanatic about the American West, to view history as stories…woven around incisive biographies…little dashes of scandal…with everything authenticated from available sources.” Brown met his future wife, Sally Stroud of Wilson (Mississippi County), when they were both students there. They had two children.

At the height of the Depression, Brown traveled to Washington DC to find a job, and he worked in the U.S. Department of Agriculture library. He earned a BLS (Bachelor of Library Science) degree in 1935 from George Washington University. Months before he was drafted into the U.S. Army during World War II, Brown wrote his first book, Wave High The Banner (1942), a novel inspired by the Davy Crockett stories he had heard his grandmother tell. During most of his tour of duty, Brown had access to the National Archives (he did not serve overseas), including a complete photographic record of the American westward expansion. Under the tutelage of Scribner’s famous editor, Maxwell Perkins, Brown co-authored three profusely illustrated volumes of frontier history (published in 1948, 1952, and 1955), which launched his writing career.

In the 1950s, Brown received his MLS (Master of Library Science) degree at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, where he was librarian at the College of Agriculture until he retired in 1972. During this time, he wrote two critically acclaimed Civil War histories and the bestselling book, The Gentle Tamers: Women of the Old Wild West (1958).

During the 1950s and 1960s, Brown wrote many westerns, a humorous novel, more histories, and many books for young adults, such as Showdown at Little Big Horn (1964). One of the histories, Grierson’s Raid (1954), was praised by academic reviewers as “a minor classic of its kind… turning unusually interesting source materials (an unpublished autobiography, family journals, letters, papers) into a graphic story of military adventure” about a 600-mile Union foray into Confederate territory in 1863.

In the late 1960s, Brown began writing his groundbreaking book, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, which has sold more than five million copies around the world. The New York Times described the book as “a grim, revisionist tale of the ruthless mistreatment and eventual displacement of the Indian by white conquerors from 1860 to 1890.” However, Brown said the best compliment he ever received for the bestseller came from a Native American: “You didn’t write that book. Only an Indian could have written that book!” Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee continues to be translated into many foreign languages, most recently in Korean, Serbian, and Turkish.

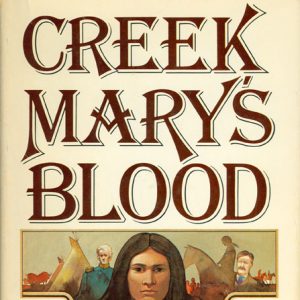

Brown spent twenty-seven productive years after retirement in Little Rock, writing such works as a bestselling novel, Creek Mary’s Blood (1980), and a critical account of the Union Pacific Railroad, Hear That Lonesome Whistle Blow (1977). Way To Bright Star (1998), written when he was ninety, was the last of the eleven novels he wrote.

His attachment to Arkansas surfaced in his writings during these later years. His illustrated history, The American Spa: Hot Springs, Arkansas (1982), includes candid stories about the state’s mecca for tourism, such as the dispute, in 1877, among town leaders concerning the use of Hot Springs Reservation’s thermal waters by the poor. He also published a memoir, When the Century Was Young, in 1993.

Some professional historians criticized Brown for writing “popular history,” for “focusing on Indian interactions with soldiers and settlers rather than on their society and culture,” and for his “willingness to sacrifice precision for pizzazz,” criticism to which he reportedly responded like the librarian he was: “I have the documents to prove everything.”

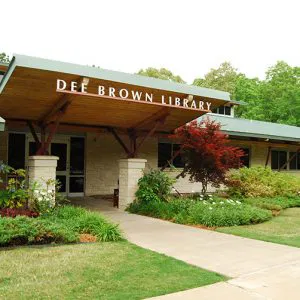

Brown died on December 12, 2002, at the age of ninety-four at his home in Little Rock. A memorial service was held at the Main Library of the Central Arkansas Library System, which has a branch library in Little Rock named for Brown. His remains are interred in Urbana, Illinois.

For additional information:

Brown, Dee. Best of Dee Brown’s West: An Anthology. Edited by Stan Banash. Sante Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers, 1998.

———. When the Century Was Young. Little Rock: August House, 1993

Courtemanche-Ellis, Anne. “Meet Dee Brown: Author, Teacher, Librarian.” Wilson Library Bulletin 52 (March 1978): 552–561.

Dee Brown Papers. Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Lancaster, Bob. “Won by the West.” Arkansas Times, August 10, 2001, pp. 11–15.

Moritz, Charles, ed. Current Biography Yearbook, 1979. New York: H. W. Wilson Co., 1980.

Razer, Bob. “Dee Brown, 1908–2002: Arkansan, Librarian, Historian.” Arkansas Libraries 60 (February 2003): 1, 7–11.

Anne Courtemanche-Ellis

Lurton, Arkansas

In 1987, I drove Mr. Brown over to Tulsa, Oklahoma, to attend the premiere of a play based on his book Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. David Carradine starred in the production, and Will Sampson, a fairly famous Native American actor, also had a part in it. (Sampson might be best known for his role as Chief Bromden in the film version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.) At the cast party after the play, Sampson told me: “A lot of Native Americans consider Dee Brown to be a god. He’s the only white man who ever told the story from the Indian’s point of view.”