calsfoundation@cals.org

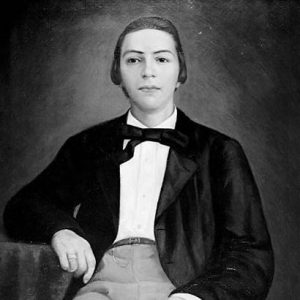

David Owen Dodd (1846–1864)

During the Civil War, seventeen-year-old David Owen Dodd of Little Rock (Pulaski County) was hanged as a spy by the Union army. He has been called the “boy hero of Arkansas” as well as “boy martyr of the Confederacy.” His story has inspired tributes such as the epic poem The Long, Long Thoughts of Youth by Marie Erwin Ward, a full-length play, and even reportedly a 1915 silent Hollywood movie, which has not survived. Historical markers, monuments, annual reenactments of his execution, and the naming of the David O. Dodd Elementary School in southwest Little Rock are among the state’s recognitions of his life and death.

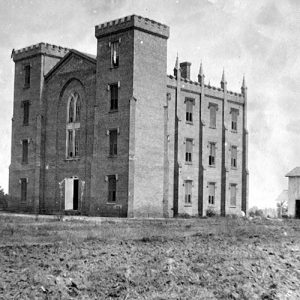

David Owen Dodd was born on November 10, 1846, in Lavaca County, Texas, to Lydia Echols Owen Dodd and the merchant Andrew Marion Dodd; he had two sisters, Leonora and Senhora. They moved to Little Rock to be closer to Senhora’s school, and young Dodd attended St. Johns’ College, located on the grounds of present-day MacArthur Park. After less than a year, Dodd left St. Johns’ when he became ill with malaria, but he hoped to return. Meanwhile, he worked as a clerk and learned Morse code at the telegraph office.

When the Union army occupied the city in 1863, the Dodd family evacuated south to Camden (Ouachita County), behind Confederate lines. On December 24, 1863, Dodd’s father sent him to Little Rock on business, thinking he would be safe since he was underage for the army. Confederate General James F.Fagan issued the boy’s pass and supposedly said, in what may or may not have been a joke, that he would expect a full report upon Dodd’s return.

Dodd rode a mule to Little Rock, carrying a birth certificate showing he was underage along with his pass. He attended holiday parties, where he met the teenage Mary Dodge, described by one of her descendants as an “ardent little Rebel.” Union officers were quartered in the Dodge home, which Dodd was invited to visit.

Dodd left Little Rock on December 29. Union sentries took his pass, as he did not expect to return. After spending the night with his uncle Washington Dodd southwest of Little Rock, Dodd traveled through the woods and found himself back behind Union lines.

He was stopped in what is now west Little Rock, near Ten Mile House on Stagecoach Road, and discovered to be without a pass. When he was asked for identification, Dodd showed his small leather notebook, where Union soldiers found not only his birth certificate but also a page with dots and dashes. A Union officer had worked for the telegraph office and easily read the Morse code message, which contained exact information about Union troop strength in Little Rock.

Dodd was arrested, convicted by a court-martial of being a spy, and sentenced to execution by hanging. He was taken to the Little Rock Arsenal, where, according to the legend that has built up around the event, Union General Frederick Steele repeatedly offered to release Dodd in exchange for the name of his informant, to which Dodd is said to have replied, “I can give my life for my country but I cannot betray a friend.” However, Dodd’s sister, Senhora Dodd Booth, claimed in later years that her brother likely acted alone, “inspired only by the hope of serving his country.”

On January 8, 1864, a bitterly cold day when the Arkansas River was frozen solid, Dodd was hanged on the grounds of his former school, St. Johns’, just east of the Little Rock Arsenal. According to legend, before horrified onlookers who had crossed the river to witness his execution, the hangman’s rope stretched and the boy dangled, strangling to death over a full five minutes; onlookers as well as Union soldiers became ill at the tragic spectacle. However, there is little in the historical record to support this claim of universal revulsion; some records seem to indicate that his death was relatively quick, while Lieutenant James Munns Jr. of the Twenty-ninth Iowa wrote in a letter, “I was pleased to have the satisfaction of seeing a double-dyed traitor, who was arrested as a ‘spy’ hung by the neck until life had departed.”

David O. Dodd is buried in the southeast portion of Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock, in a grave that was donated by a Little Rock resident at the time of the boy’s death. Questions about his actions remain unanswered: Where did the information in the Morse-coded message come from? Whom was he protecting (if anyone)? Did he knowingly re-cross enemy lines or did he just get lost?

The execution of Dodd was little remarked upon at the time, but he was raised to heroic status in the postwar years with the growth of “Lost Cause” ideology. The Arkansas Division of the United Daughters of the Confederacy raised funds for a stained-glass window in his honor. In 1911, it was presented to the Confederate Museum in Richmond, Virginia, as a memorial window for the Arkansas Room. The window was loaned to the Arkansas Museum of Science and Industry in Little Rock during the 1990s and again in 2004 for a commemorative program at the renamed MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History (formerly the Little Rock Arsenal).

On November 10, 1923, the David O. Dodd Memorial was dedicated at the state War Memorial, which later became the Old State House Museum. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 26, 1996.

Each January, the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) honor Dodd at Mount Holly Cemetery in a ceremony concluding near the eight-foot marble monument at the boy’s grave, which is engraved, “Here lie the remains of David O. Dodd. Born in Lavaca County, Texas, Nov. 10, 1846, died Jan. 8, 1864.” Nearby is a marble scroll with the words, “Boy Martyr of the Confederacy.” In 1984, the SCV awarded Dodd the Confederate Medal of Honor.

For additional information:

Captain Benjamin Tolbert Humphrey Diaries. MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Christ, Mark K. “‘There was a Rebel Spy hung here on Friday’: Little Rock Letters from Harvey R. Frazer, Thirteenth Illinois Cavalry.” Pulaski County Historical Review 71 (Fall 2023): 88–97.

David O. Dodd Papers. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Fischer, LeRoy H. “David O. Dodd: Folk Hero of Confederate Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 37 (Summer 1978): 130–146.

Herndon, Dallas. The Memorial to David O. Dodd, Arkansas Boy Hero. N.p.: 1913.

Lair, Jim. Boy Hero of the Confederacy: The Life, Legend and Execution of David Owen Dodd. Springfield, MO: Oak Hill Publishing, 2001.

McMath, Phillip H. “History? Legend? Symbol?: The Story of David O. Dodd.” Pulaski County Historical Review 61 (Winter 2013): 107–117.

———. “The Trial of David O. Dodd: ‘A Political Pawn.’” Pulaski County Historical Review 64 (Winter 2016): 138–157.

Moneyhon, Carl H. “David O. Dodd, the ‘Boy Martyr of Arkansas’: The Growth and Use of a Legend.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 74 (Autumn 2015): 203–230.

Ward, Marie Erwin. “The Long, Long Thoughts of Youth: The Story of David Owen Dodd.” Arkansas Democrat Sunday Magazine. November 9, 1958, pp. 3–5.

Nancy Hendricks

Arkansas State University

David O. Dodd Monument

David O. Dodd Monument  David O. Dodd

David O. Dodd  David O. Dodd Poem Recitation

David O. Dodd Poem Recitation  David O. Dodd Stained-Glass Window

David O. Dodd Stained-Glass Window  David O. Dodd Gravesite

David O. Dodd Gravesite  Gann Museum

Gann Museum  St. Johns' College

St. Johns' College

My aunt is in her 80s and living in a nursing home in Conway, Arkansas. She was asked to recite a poem about David Owen Dodd at a citywide celebration when she was sixteen years old. For all of these years, she has recalled this poem and on a recent visit, recited it once more. She now suffers from Alzheimers, but she remembers it word for word. I recorded it while visiting with her. [Editor’s note: See audio media file also with this entry: https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/media/david-o-dodd-poem-8280/.%5D