calsfoundation@cals.org

Civil War Veterans' Reunions

After the Civil War, Arkansas veterans returned home and attempted to revert to civilian life, a task very difficult in a destitute, disrupted, and divided state. During the immediate postwar decades, veterans and their families began to establish veterans’ cemeteries, hold memorial services for the dead, build monuments, conduct unit reunions, and organize veterans’ groups. Reunions, perhaps the most important outlet for the ex-soldiers, allowed veterans to communicate with others who had shared the experience of Civil War combat and the difficulties of returning to civilian life. A decade after the end of the war, veterans began to realize that including their old adversaries in reunions could help mend the wounds of the war. Toward the beginning of the twentieth century, the activities and meanings of reunions changed as veterans sought a lasting legacy as they began to fade away.

Early veterans’ activities, including the first reunions, typically focused on providing aid for destitute veterans and their dependents, a trend followed by reunions in Arkansas. In 1866, Daniel Harris Reynolds, former Confederate brigadier general and a senator in the state legislature, announced a reunion of Reynolds’s Arkansas Brigade in November to provide for widows and orphans as well as disabled and needy veterans. Furthermore, he wanted to write a “true history” of the unit, a common activity at other early veterans’ reunions. These histories often served as personal vindications of honor, explaining why a culture based on a strong honor system lost the war, thus creating the “Lost Cause” mythology. This literary and intellectual movement sought to reconcile the traditional white society of the South to the Confederate defeat by portraying the Confederacy’s cause as noble and most of its leaders as exemplars of old-fashioned honor, defeated by the Union army because of its greater resources rather than superior military skill.

In the mid-1870s, Union and Confederate veterans began to attend events held by the opposing side, beginning the era of joint reunions. These events varied in size ranging from fewer than twenty people, such as the 1875 reunion of the Old Pike Guards in Fayetteville (Washington County), to the combined Little Rock Fair Week reunions of Daniel Harris Reynolds’s, Daniel Chevilette Govan’s, and Thomas Churchill’s brigades in October 1879. With hundreds of Confederate veterans at the reunion during Fair Week, this event differed slightly from other Arkansas reunions of the 1870s. Some Union soldiers attended the event, and two Union officers delivered orations, each focusing on the topic of reconciliation between the honorable foes. Black Union veterans were apparently not included in such gatherings.

This desire to work together continued into the 1880s and early 1890s, resulting in a shift from smaller joint reunions to the larger type known as Blue-Gray reunions. The largest of these in Arkansas was held in 1889 at Pea Ridge (Benton County), drawing more than 7,000 people and attracting more Union than Confederate veterans. Participants camped on the grounds, had access to vendors, and gathered for dining, dancing, and speeches. The pinnacle of the reunion was the unveiling of the monument for all survivors. The monument’s symbols of unity included a pair of clasping hands and the words “A REUNITED SOLDIERY.” If the monument and speeches at Pea Ridge were any indication, combined reunions allowed veterans to obtain catharsis and publicly make overtures toward making amends with their former enemies.

While some early veterans’ groups existed in Arkansas prior to the 1880s, such as individual posts of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) and local ex-Confederate groups, the creation of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV) in the late 1880s led to another phase of reunions, those sponsored by veterans’ groups—with Blue-Gray reunions eventually being phased out. The emergence of state and national veterans’ groups made organizing larger events possible. By the end of the 1890s, these events had become common for both the UCV and the GAR. Both groups ran their activities in a military style, similar to the structure of the veterans’ organization, with a commander of the camp and various officers to help run the function. In 1897, General V. Y. Cook officiated at the reunion held by the Tom Hindman Camp of the UCV near Jacksonport (Jackson County). This event also had a mock battle in which the old Confederate veterans and the Sons of Confederate Veterans, an organization for the male descendants to assist the aging veteran organization, formed infantry, cavalry, and artillery units and expended some 6,000 blank rounds. Afterward, a mock court-martial was held, complete with the sentencing and execution of a private accused of desertion. While reconciliatory tones were still used at veterans’ group reunions, these specific events gave groups like the UCV the ability to discuss and promote their version of the war, thus promoting the “Lost Cause” ideology with no real resistance.

Toward the turn of the century, the reunion process began to be less of a catharsis for veterans. Rather, the aging veterans used reunions as an opportunity to reminisce and feel young again. Others used this opportunity to drink or carouse while taking a break from the changes of modern life. Veterans also hoped these reunions would teach the younger generation about “manly” behavior and traditional values.

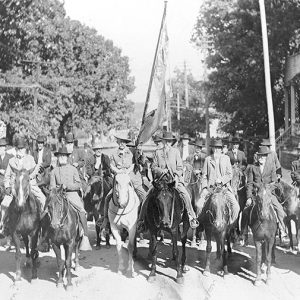

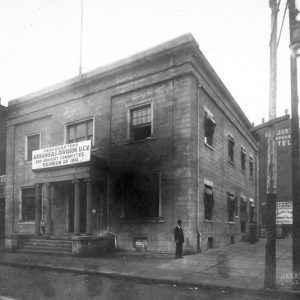

After 1900, UCV- and GAR-sponsored events were the most commonly held; however, the passing years began to thin the number of attendees. In Arkansas, three national Confederate reunions held during the early to mid-twentieth century represent the changes: the twenty-first UCV reunion held in Little Rock (Pulaski County) on May 16–18, 1911; the thirty-eighth UCV reunion in Little Rock on May 8–11, 1928; and the fifty-ninth UCV reunion in Little Rock on September 27–29, 1949. The number of participants dropped from 12,000 veterans in 1911, to 3,000 in 1928, to four in 1949. Photographs of the parades in 1911 and 1928 illuminate the challenges facing the veterans as they aged. In 1911, the veterans marched with crowds of admirers along the route, with newspapers making only minor references to aging veterans’ physical problems. By 1928, only one veteran walked the parade route while the rest rode in cars or in the backs of trucks. By 1949, the average age of the attendees was 100.5; this reunion may have been the last Civil War reunion in Arkansas.

While veteran activities waned, the efforts to use reunions to promote different versions of the war continued. The reunion photographs of 1911 show an event arranged for the transference of information concerning the “Lost Cause,” an excessively important function to these aging Confederate veterans. Spectators saw drill demonstrations promoting the southern military culture. Images of southern heroes were posted at venues and along the parade route, and the establishment of the Capital Guards (Company A, Sixth Regiment Arkansas Infantry) monument in the City Park near the Little Rock Arsenal honored local veterans as heroes. These public interactions are critical in the maintenance of the Confederate version of the war.

By the time of the 1928 event, the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV), the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), and the Confederate Southern Memorial Association were carrying the mantel for the old Confederates, who ranged in age from seventy-eight to 107 years old. Holding their reunions at the same time as the UCV reunions, these groups organized and ran many of the activities for the old veterans. The deaths of the final veterans did not end the promotion of the “Lost Cause” mythology in Arkansas. Even in the twenty-first century, Confederate descendants continue holding state and national gatherings with active SCV and UDC groups in the state. However, while Arkansas has a Sons of Union Veterans group, there is no evidence that the group holds yearly meetings in the twenty-first century.

For additional information:

Black, J. Dickson. The History of Benton County. Little Rock: International Graphics, 1975.

Foster, Gaines M. Ghost of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South, 1865 to 1913. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Hanley, Ray, and Steven G. Hanley. Remembering Arkansas Confederates and the 1911 Little Rock Veterans Reunion. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006.

McConnell, Stuart. Glorious Contentment: The Grand Army of the Republic, 1865–1900. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

Polston, Mike. “Little Rock Did Herself Proud: A History of the 1911 United Confederate Veterans Reunion.” Pulaski County Historical Review 29 (Summer 1981): 22–32.

Shea, William L., and Earl L. Hess. Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992.

Derek Allen Clements

Black River Technical College

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.