calsfoundation@cals.org

Chordate Parasites

aka: Parasitic Chordates

Although the majority of the world’s parasites are protists, helminths, invertebrates, and other miscellaneous groups of organisms, parasitism has also arisen within animals of the phylum Chordata (subphylum Vertebrata). All chordates, at some time in their development, possess five derived morphological characteristics as follows: (1) a dorsal tubular or hollow nerve cord, (2) a notochord, (3) pharyngeal gill slits or pouches, (4) an endostyle, and (5) a post-anal tail. Some examples of parasitic chordates are remoras (which attach to sharks and rays); the jawless fishes (lampreys and hagfishes), which prey upon other fishes; some birds that practice brood parasitism; and vampire bats.

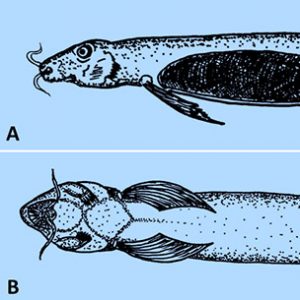

The Superclass Agnatha has both extinct groups and extant species, including the “jawless” fish (lamprey and hagfish) that lack jaws, paired fins, and scales. The family Petromyzontidae (lampreys) includes about eight genera and forty-two species of lampreys; of these, about eighteen species (forty-three percent) are parasitic. Although most are free-living, the parasitic species attack fish, weakening or outright killing them. Their sucker-like mouth possesses rows of teeth, and the tongue is rasp-like, which helps it bore into the sides of fish and suck out blood, tissue fluid, and/or viscera. There is a single nostril on the dorsal surface of head, external gill openings, a complete braincase, a simple two-chambered heart, and rudimentary vertebrae. From their lake or sea habitats, the anadromous marine lampreys migrate up rivers to spawn (followed by the death of the spawning adults); females deposit a large number of eggs in nests made by males in the substrate of streams with moderately strong current. Larvae called ammocoetes burrow in sand and silt in quiet water downstream from spawning areas, remain sedentary, and strain organic matter and plankton. They resemble adults in body form but lack the typical sucking disc, rasping teeth, and eyes of the adult, and they have a hood covering the mouth. After one to three years in freshwater habitats, the larvae undergo a transformation that allows young post-metamorphic lampreys to migrate to the sea or lakes and start their hematophagous feeding. Unidentified ammocoetes (likely both parasitic and non-parasitic species) have been reported from various watersheds in Arkansas from Carroll, Clark, Fulton, Madison, Marion, Newton, and Searcy counties.

One of the most well-known lamprey species is the sea lamprey, Petromyzon marinus, native to the Northern Hemisphere. It is considered a major pest in the Great Lakes region. Improvements in 1919 to the Ontario, Canada, Welland Ship Canal are thought to have allowed P. marinus to spread from Lake Ontario into Lake Erie, and it soon ranged into Lakes Huron, Michigan, and Superior, where it devastated indigenous fish populations in the 1930s and 1940s. Since then, P. marinus continues to create problems with their aggressive parasitism on game fish and key predator species, such as chub, lake herring, lake trout, and lake whitefish. Elimination of these predators allowed another invasive species, the Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus), to explode in population, compounding adverse effects on many native fish species. The sea lamprey is an aggressive predator by nature, which gives it a competitive advantage in a lake system, where its prey lacks defenses against it and where it has no predators.

In Arkansas, there are two species of parasitic lampreys, the chestnut lamprey (Ichthyomyzon castaneus) and silver lamprey (I. unicuspis). The former is found in clear streams of the Arkansas, Buffalo, Caddo, Illinois, Little, Ouachita, Petit Jean, Saline, and White rivers, where they prey upon an abundance of large riverine fishes. Spawning adults can be found in medium creeks to large rivers, and larvae require clear streams with permanent flow, stable sand bars, silt, and organic matter. Some estimates of fecundity (number of eggs produced) range from about 10,000 to 20,000 eggs per female. One specimen of the chestnut lamprey was attached to a Moxostoma (redhorse) sucker collected at the Saline River in Drew County, and specimens have also been reported from various trout on Norfork Lake in Baxter County. However, this lamprey is not considered common enough to cause any problems with fisheries in the state. On the other hand, the silver lamprey was not known from the state until it was reported in 2011, when fifteen adult I. unicuspis were found attached to paddlefish (Polyodon spathula) collected from the White River near the confluence of the Black River in Independence and Jackson counties. Two additional specimens of I. unicuspis were also collected from the Buffalo and White rivers in Marion and Prairie counties, respectively. It has been reported to produce up to 19,000 ova per female. Although much is known about I. unicuspis in adjacent Tennessee, additional research is sorely needed on this lamprey in Arkansas.

The hagfishes (family Myxinidae) are strictly marine and include six genera and about seventy-eight species. They are considered more primitive than lampreys and have direct development without a larval stage. Hagfishes are elongate slender fishes that produce copious amounts of slime. There are four pairs of sensory tentacles around the mouth, two pairs of rasps on the tongue (used to tear off chunks of prey tissue), three accessory hearts, and a partial braincase. They are generally found in cold oceans, often living on a muddy bottom and in large groups of individuals where they feed on bristle worms (polychaetes) and other invertebrates. They occasionally target healthy fish, but more often scavenge on dead or dying fish. Hagfishes are consumed as food in parts of Asia, and their skin is processed into “eel skin.”

There are three genera and about eight species of parasitic remoras (Osteichthyes: Echeneidae) that occur in the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans. There are eight genera and thirty-six species of pearlfishes or cusk eels (Ophidiiformes: Carapidae) that live symbiotically within benthic (deep-water) invertebrates. The relationship of the fish to the host is quasi-parasitic; only in a few cases is the association considered overt parasitism. In most cases, the fish either consumes food that could be used by the host or simply takes up space. One representative species is the pearlfish (Carapus acus), that resides within the anus of holothurians (sea cucumbers) in the eastern Atlantic.

There are about 210 species of parasitic male fishes in the order Lophiiformes commonly termed “anglerfish,” “dreamers,” “monkfish,” “toadfish,” and “sea-devils.” Members from at least four families contain some deep-sea species with parasitic males. Males are small, and attach to the female with their teeth. The teeth and jaw then gradually recede, and the circulatory systems of the two fish merge and they become irreversibly joined. Parasitic males then provide a constant supply of sperm to the female.

The fish family Trichomycteridae (order Siluriformes) contains forty-one genera and 207 described species of freshwater fish commonly referred to as the “pencil catfish” or “parasitic catfish.” Representative species are distributed throughout Costa Rica, Panama, and South America, but all members of this fish family are banned from import into the United States.

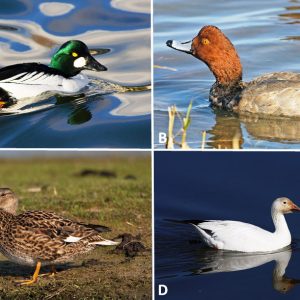

About one percent of all birds (about 103 species) practice brood parasitism. This is a parasitic association where one bird (the parasitic species) lays its eggs within the nest of another bird (the host or foster bird species). The fostering bird then cares for the offspring of the invader. Some species of birds reject the eggs of a brood parasite, whereas others will accept the egg. A number of ducks (family Anatidae) found in Arkansas display various types of brood parasitism, both intra- and inter-specific. Because their young are precocial (up and active soon after hatching), the impact of the parasitism on the host tends to be low. For example, the female common goldeneye duck (Bucephala clangula) can double her reproductive output by combining brood parasitism with normal nesting. She will lay her eggs within other goldeneye nests and also nests of a variety of other species of waterfowl. In addition, the redhead duck (Aythya americana) will lay eggs not only in their own nests, but also the nests of conspecifics and other types of waterfowl. Other known anatid brood parasites found in Arkansas include ruddy ducks, canvasbacks, northern shovelers, mallards, gadwalls, and northern pintails. One of the most famous brood parasites is the brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater), which also occurs in the state. Brown-headed cowbirds tend to use neotropical migrant birds as hosts, and parasitism has been so successful that populations of some of these migrants are declining, with up to seventy percent of the nests of some hosts being parasitized. The female cowbird will lay an egg within a nest (usually just before sunrise) after the host has already laid two or more eggs but before incubation has begun. The female cowbird usually removes one or more of the host eggs by piercing the egg with her bill and carrying it away to be eaten. If the cowbird egg is too dissimilar to the host eggs, however, some birds will abandon their nest altogether or remove the cowbird eggs. Some other avian species actually practice intraspecific brood parasitism, in which they place eggs within the nests of members of their own species. This also includes species known from Arkansas such as snow geese (Chen caerulescens) and American cliff swallows (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota).

Although none of the sixteen species of bats (class Mammalia, order Chiroptera) that occur in Arkansas are considered parasitic, the hairy-legged vampire bat (Diphylla ecaudata) ranges as far north as extreme southern Texas and does practice parasitism. It tends to be timid and feeds primarily on bird blood.

For additional information:

Andersson, M., and M. O. G. Eriksson. “Nest Parasitism in Goldeneyes Bucephala clangula: Some Evolutionary Aspects.” American Naturalist 120 (1982): 1–16.

Chesser, R. Terry, Kevin J. Burns, Carla Cicero, Jon L. Dunn, Andrew W. Kratter, Irby J. Lovette, Pamela C. Rasmussen, J. V. Remsen Jr., James D. Rising, Douglas F. Stotz, and Kevin Winker. “Fifty-Eighth Supplement to the American Ornithological Society’s Check-list of North American Birds.” The Auk 134 (2017): 751–773.

Cochran, Phillip A., M. R. Gehl, and J. Lyons. “Parasitic Attachments by Overwintering Silver Lampreys, Ichthyomyzon unicuspis, and Chestnut Lampreys, Ichthyomyzon castaneus.” Environmental Biology of Fishes 68 (2003): 65–71.

Greenhall, Arthur M., Uwe Schmidt, and Gerhard Joermann. “Diphylla ecaudata.” Mammalian Species 227 (1984): 1–3.

Lyon, Bruce E. “Egg Recognition and Counting Reduce Costs of Avian Conspecific Brood Parasitism.” Nature 422 (2003): 495–499.

Mallatt, J., and J. Sullivan. “28S and 18S Ribosomal DNA Sequences Support the Monophyly of Lampreys and Hagfishes.” Molecular Biology and Evolution 15 (1998): 1706–1718

Martini, F. H. “The Ecology of Hagfishes.” In The Biology of Hagfishes, edited by J. M. Jørgensen, J. P. Lomholt, R. E. Weber, and H. Malte. London: Chapman and Hall, 1998.

Melhorn, Heinz. “Myth and Reality: Candiru, the Bloodsucking Fish that May Enter Humans.” Parasitology Research Monographs 5 (2013): 179–181.

Nielsen, Jørgen G. Encyclopedia of Fishes. Edited by J. R. Paxton and W. N. Eschmeyer. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998.

Pietsch, Theodore W. Oceanic Anglerfishes: Extraordinary Diversity in the Deep Sea. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

Robison, Henry W., and Thomas M. Buchanan. Fishes of Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1988.

Robison, Henry W., William T. Slack, Steven G. George, and Chris T. McAllister. “First Record of the Silver Lamprey, Ichthyomyzon unicuspis (Petromyzontiformes: Petromyzontidae), from Arkansas.” American Midland Naturalist 166 (2011): 458–461.

Robison, Henry W., Renn Tumlison, and James C. Peterson. “New Distributional Records of Lampreys from Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 60 (2006): 194–196. Online at http://scholarworks.uark.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1523&context=jaas (accessed February 17, 2018).

Rothstein, S.I. “A Model System for Coevolution: Avian Brood Parasitism.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 21 (1990): 481–508.

Silva, S., M. J. Servia, R. Vieira-Lanero, and F. Cobo. “Downstream Migration and Hematophagous Feeding of Newly Metamorphosed Sea Lampreys (Petromyzon marinus Linnaeus, 1758).” Hydrobiologia 700 (2013): 277–286.

Teuschl, Y., B. Taborsky, and M. Taborsky. “How do Cuckoos Find Their Hosts? The Role of Habitat Imprinting.” Animal Behaviour 56 (1998): 1425–1433.

Tumlison, Renn, and Henry W. Robison. “New Records and Notes on the Natural History of Selected Vertebrates from Southern Arkansas.” Journal of the Arkansas Academy of Science 64 (2010): 145–150. Online at http://scholarworks.uark.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1393&context=jaas (accessed February 17, 2018).

Chris T. McAllister

Eastern Oklahoma State College

Science and Technology

Science and Technology Arkansas Anatids

Arkansas Anatids  Brown-Headed Cowbird

Brown-Headed Cowbird  Candiru

Candiru  Parasitic Lampreys

Parasitic Lampreys

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.