calsfoundation@cals.org

Blytheville (Mississippi County)

County Seat

| Latitude and Longitude: | 35º55’38″N 089º55’08″W |

| Elevation: | 259 feet |

| Area: | 20.74 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 13,406 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | January 4, 1892 (accounts vary) |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

302 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

3,849 |

6,447 |

10,098 |

10,652 |

16,234 |

20,797 |

24,752 |

23,844 |

22,906 |

18,272 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15,620 |

13,406 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

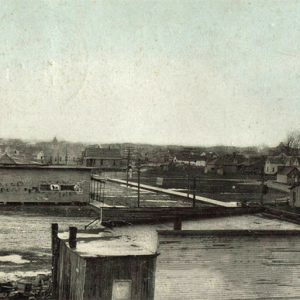

Blytheville is located in the low, flat Mississippi Delta on land that was inhabited by Native Americans for thousands of years. Two prominent natural forces shape Blytheville. The first is the New Madrid Seismic Zone. Blytheville, which is prone to tremors, lies near the epicenters of the record-setting New Madrid Earthquakes of 1811–1812. Almost two centuries later, abundant evidence of these quakes is still visible in the Blytheville area. The second shaping force is the Mississippi River. The river’s impact includes flooding (such as in 1882–83 and the Flood of 1927), the creation of fertile farming soil, and providing waterway transportation for industry.

Early Statehood through the Gilded Age

Blytheville, originally known as Blythesville, is named for the Reverend Henry T. Blythe (1816–1904). H. T. Blythe settled in Mississippi County in 1853 and farmed land in Crooked Lake (now Armorel) between modern-day Blytheville and the Mississippi River. He was ordained to preach in the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1862.

In 1880–81, Blythe designed and formally launched the new town of Blytheville (or Blythesville) on lots filling 160 acres of land situated between the preexisting settlements of Cooketown (also known as Chickasawba) and Clear Lake. Blytheville and its neighbor, Gosnell, later blossomed at the expense of these older communities. Sources give conflicting dates for Blytheville’s incorporation: May 1891, January 1892, and May 1889.

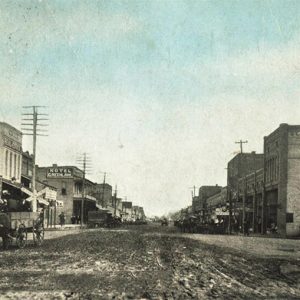

The early growth of Blytheville was spurred by the massive harvesting of lumber to rebuild after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and the lumber industry brought sawmills and a rowdy crowd. The Blytheville area was known as a loud and disreputable place during the 1880s and 1890s, given the prevalence of a saloon culture there.

Blytheville first received a post office in 1879, but the postal situation was unstable due to rivalries and redundancies among Cooketown, Blytheville, and Clear Lake. After considerable political wrangling, Blytheville permanently gained the area’s post office in 1890 and became the county seat for the northern half of Mississippi County (Chickasawba District) in 1901.

Early Twentieth Century

A combination of the quality of cleared land left behind after the area was successfully stripped of lumber, the low cost of this fresh farmland, and the success of ongoing levee building and waterway management efforts brought agriculture to the fore in Blytheville and drew farmers to the area during the first three decades of the twentieth century.

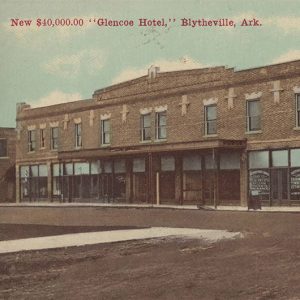

In the city’s Diamond Jubilee text, Maureen King Norris documented the arrival of electricity and telephone service to Blytheville in 1903, with natural gas service not arriving until 1950. The railroads reached into Blytheville during the first decade of the twentieth century and accelerated the young city’s growth. The Mississippi County Courthouse in the Chickasawba District was dedicated in 1921. Sadly, most of the records regarding Rev. Blythe and Blytheville’s origins burned in a 1926 fire at First Methodist Church.

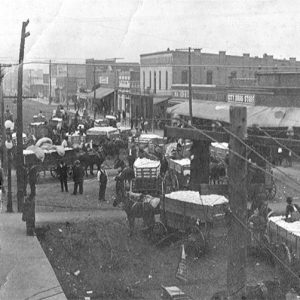

Blytheville suffered terribly during the Great Depression, the effects of which came to Blytheville early in the Depression years because the agricultural community’s economic well-being was so strongly tied to the commodities market, particularly cotton. According to Jonathan Abbott, Blytheville historian and collector of northeast Arkansas historical memorabilia, during the Depression: “Everything just came to a stop. Some people kept farming. But everyone just hunkered down.” With the depletion of lumber, there was no industry to speak of in Blytheville during the Great Depression. Agriculture was dominant, and many farmers lost their land due to inability to repay financing. Thousands of people were destitute and hungry.

Influenced by the Flood of 1927 and the Great Depression, Mississippi County farmers were a dynamic force in the growth of the Arkansas Farm Bureau during the 1920s and 1930s.

For much of its history, Blytheville had a thriving Jewish community. Several early Main Street merchants were Jewish. Lawyer Oscar Fendler practiced here. The congregation that would become Temple Israel formed in 1924 and settled into its building in 1947. The congregation declined as the twentieth century came to a close. Most of the surviving members relocated to other areas, including Memphis, Tennessee, and Little Rock (Pulaski County), and Temple Israel officially closed in 2003. In conjunction with organizations such as the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life, the congregation saw its Torah scrolls and other important objects and records carefully dispersed and stored. While Temple Israel’s building still stands on Chickasawba Street and is privately owned, its stained-glass windows are now part of Memphis’s Beth Sholom synagogue.

World War II through the Modern Era

The U.S. military first opened an army airfield in Blytheville in 1942, deactivating it in 1945. The base was reactivated as Blytheville Air Force Base in the 1950s and renamed Eaker Air Force Base in 1988. It served as the home of the Ninety-seventh Bombardment Wing of the Strategic Air Command, and the base housed many B-52s. The federal government closed the base in 1992, which was a devastating blow to the Blytheville community. At its peak, it employed approximately 3,500 military personnel and 700 civilian support staff, and upon the closure of the base, the Blytheville/Gosnell area lost about 6,500 people, including the families of service members transferred elsewhere. The former base is now the Arkansas Aeroplex and houses both aviation and non-aviation-related businesses. Also on site are the Westminster Village retirement community, the Lights of the Delta holiday display, the Blytheville Research Station of the Arkansas Archeological Survey, Thunder Bayou Golf Links, and the Blytheville Youth Sportsplex.

The blow from the loss of the airbase was softened by the rise of the steel industry in the Blytheville area. Barge traffic on the Mississippi River and the railroads contributed to industrial growth. Nucor-Yamato Steel began production in 1988 and expanded in 1992. Nucor Steel Arkansas, locally known as Nucor Hickman, began production in 1992 and expanded in 1998. These two raw-steel producers are surrounded by several steel-related industries, including Maverick Tube, IPSCO Inc., and Milwaukee Electric Tool.

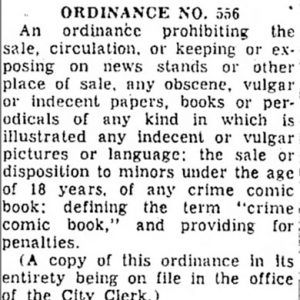

On January 18, 1955, the city council passed Ordinance 556, which levied fines of up to $100 for the sale of “any crime comic book” to anyone younger than eighteen. The ban on comic books was part of a national moral panic about the content of such periodicals.

Mississippi County has long held its place as the number one cotton-producing county in Arkansas, and Blytheville sits near ten cotton gins. One of the largest cotton gins in North America lies on Blytheville’s western edge. The area is also blanketed with soybean and rice fields. Mississippi County was ranked as the third highest soybean-producing county in Arkansas in 2004. The county also produces the feed grains corn and milo (sorghum) and a winter crop of soft red winter wheat which rotates in some soybean fields.

Modern farming in Blytheville has followed the trend of larger farms held by fewer farmers. Changing farming equipment and a shift toward more irrigated acreage also influence Blytheville farming. Transgenic crops designed for pesticide/herbicide use are revolutionizing Blytheville farmers’ planting.

Education

Functioning under a “separate but equal” clause in the state constitution, by the late 1960s, Blytheville’s African American high school students had “freedom of choice” to transfer from Harrison High School, for Black students, to the white Blytheville High School. A few Black students chose to do so in order to receive a college preparatory education. However, other grade levels were still segregated. A federal court judge in Jonesboro (Craighead County) ordered total integration of Blytheville schools in 1970. The school board complied, closed Harrison High School, and fully integrated all grades in Blytheville City Schools. That first school year, 1970–1971, Black students faced discrimination, leading to a boycott of the school in April 1971 (itself partly the result of a business boycott that occurred the previous year).

A December 1974 vote brought Mississippi County Community College (MCCC) into existence. The college opened its doors in 1975 in buildings leased from the Blytheville school district and moved onto its current campus in 1980. MCCC’s 2003 merger with Cotton Boll Technical Institute created Arkansas Northeastern College (ANC). In 2022, the college’s fall enrollment was 1,502 students, with many being part time.

Attractions

Rev. H. T. Blythe’s grave and the tombstones of early Blytheville residents are preserved in Founders Park. The park is also the former site of the Sycamore School House (circa 1853–1893) where Rev. Blythe first preached.

Kream Kastle, a local family-owned restaurant which opened in 1952, can still be visited today.

The Ritz, Blytheville’s civic center since 1981, originated in the early 1900s and has seen several owners, fires, name changes, expansions, and renovations throughout its decades on Main Street. A popular stop for famous vaudeville performers traveling from Memphis to St. Louis, Missouri, in the early twentieth century, the Ritz later became one of the first theaters in Arkansas to present talking pictures. The Ritz was fully renovated in 1950–1951 and hosted a television lounge where many Blytheville residents got their first glimpse of the new medium.

Blytheville lies along Highway 61 of blues music fame. Generations of blues musicians passed through Blytheville as they traveled from Memphis north toward St. Louis, Missouri, and Chicago, Illinois.

The 1932 Greyhound Bus Station at 109 North 5th Street is one of the few surviving Art Deco Greyhound bus stations in the United States. Entered onto the National Register of Historic Places in 1987, the station had fallen into disrepair from disuse. Purchased by community effort in 2004, the building came under the ownership of the Main Street Blytheville organization. Downtown’s Kress Building, also owned by Main Street Blytheville, is also on the National Register of Historic Places.

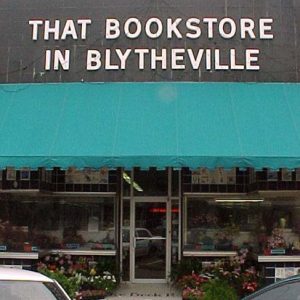

In 1976, Mary Gay Nelson Shipley opened the Book Rack, known after 1994 as That Bookstore in Blytheville (TBIB). Located in a circa-1920 building on Main Street, TBIB has put Blytheville on the American publishing map. World-renowned authors who have signed books and offered programs at TBIB include John Grisham, Bill Clinton, Hillary Clinton, Emeril Lagasse, Mary Higgins Clark, Pat Conroy, and Nicholas Sparks. The bookstore was later sold and changed names.

Visitors and residents can enjoy the annual Springtime on the Mall festival in early May and the Chili Cookoff in early October. Hunters and birdwatchers can take advantage of Blytheville’s position in the Mississippi Flyway bird migration path. Blytheville is home to the Mississippi County Fair each fall.

Notable Residents

Blytheville is the childhood home of actor George Stevens Hamilton and the birthplace of Motown musician Junior Walker, football legend Fred Akers, and speed skater Kimberly Derrick.

For additional information:

Abbott, Jonathan, and Marcy Thompson. Reverend H. T. Blythe and the Downtown He Founded. Blytheville, AR: Main Street Blytheville, 1991.

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northeast Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1889.

Blytheville, Arkansas. https://www.cityofblytheville.com/ (accessed December 29, 2025).

Blytheville, Arkansas: 75 Years of Progress Diamond Jubilee. On file at the Mississippi County Library, Blytheville, Arkansas.

Snowden, Deanna, ed. Mississippi County, Arkansas: Appreciating the Past; Anticipating the Future. Little Rock: August House, 1986.

Rigel Keffer

Blytheville, Arkansas

Trying to get old photos and history about the Lange school. Attended grades 1-4 there.

My great-great-grandfather was John Walker of Walker Park. He was the sawmill owner in the early 1900s.

I was born in Joiner, Arkansas, but my parents moved us to Blytheville when I was one year old. I lived there until the age of 15. I also attended Harrison High School and Franklin Elementary. I never attended Blytheville High because it was integrated after I left.

My grandfather, Louis Buckner, was a janitor at the First Methodist Church on Main Street. Through my research, supposedly there was a Buckner family that were members of this church and also familiar with Rev. Henry Blythe, the founder of Blytheville.

My grandmother is Maureen King Norris, mentioned here as the author of the Diamond Jubilee information. She was a journalist and a charter member of the Charlevoix Chapter of the DAR. She was married to my grandfather, Samuel F. Norris, who owned a local printing shop, was city Treasurer of Blytheville, was editor of the Commercial Appeal in Memphis, and later was known for his paintings of local luminaries.

Rev. Henry T. Blythe and my great-grandfather, J. (James) P. Kincannon, were great friends. My great-grandfather was an American Indian who became a surveyor; he and Rev. Blythe got together and surveyed the Arkansas land that my great-grandfather later named for his friend. After the town got its name, they both set up their homes there with their families.