calsfoundation@cals.org

Blytheville Comic Book Ban of 1954–1955

A national backlash against alleged violent and gory comic books led to an outright ban of such publications in Blytheville (Mississippi County) in 1955.

Many Americans were concerned about a rising rate of juvenile delinquency in the early 1950s, and some blamed magazines, comic books, and other periodicals for contributing to the problem, particularly such publications as William Gaines’s Tales from the Crypt and CrimeSuspenstories. U.S. Representative E. C. “Took” Gathings held hearings of his Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials in 1952 that looked into “gory” comic books and concluded that such magazines “do not teach children how to think straight” and recommended that publishers police themselves regarding objectionable materials.

The concern over comic books increased with the 1954 publication of psychiatrist Dr. Frederick Wertham’s Seduction of the Innocent, which maintained that the sordid content of crime and horror comics “promoted criminal and anti-social behavior in children and young adults.” While other psychiatric professionals disregarded Wertham’s book, it struck a nerve in parents and public officials concerned about juvenile delinquency, and some moved to ban such materials.

In Blytheville, Courier News reporter George Anderson conducted a survey of comic books available in the Mississippi County town in May 1954 and found many that featured “murder, violence, crime, horror, sex, seduction, fear, [and] love confessions.” He concluded that comics of the “‘crime, sex and violence’ type, in every case where they are sold, outnumber the ‘Donald Duck’ type by a wide margin.”

Winnie Virgil Turner, a school supervisor in Blytheville’s public school system, started a crusade against crime and horror comics in the city. Speaking to the local Rotary Club in October 1954, Turner decried comic books as “an invitation to illiteracy.” He said, “These publications desecrate love, marriage and the home life which we think sacred.” Blytheville’s mayor and the local prosecuting attorney pledged to support her efforts, and local publications supplier Lilly News Service vowed to “keep undesirable comic books off the newsstands.”

Turner also enlisted the Mississippi County Parent-Teacher Association into her crusade, and they decided to pursue a “comics code” similar to one that had been implemented in Santa Barbara, California. This code opposed “sexy, wanton comics,” sympathetic treatment of crime, “sadistic torture” and “vulgar and obscene language,” depictions of divorce, and ridicule or attacks on religious or racial groups. The issue was raised at the December 12, 1954, meeting of the Blytheville City Council, where Turner backed a “public censorship ordinance” that levied fines of up to $500 against merchants who sold objectionable comics to customers younger than age eighteen. The council declined to act on the request after some aldermen expressed concern about legislating censorship.

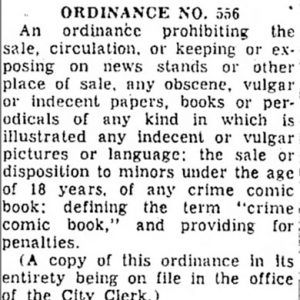

Restrictions on comic book sales came up again at the council’s January 18, 1955, meeting and the aldermen passed Ordinance 556, which levied fines of up to $100 for the sale of “any crime comic book” to anyone younger than eighteen. The council suspended its rules requiring three readings of a proposed ordinance and passed 556 with an emergency clause that enabled it to take effect immediately. Winnie Virgil Turner was named Blytheville’s Woman of the Year by the Beta Sigma Phi chapter later that year for her role in the fight against “objectionable” comics.

State Representative James J. “Red” Edwards then attempted to make comic book restrictions state law, filing a bill in February 1955 in the Arkansas General Assembly to make the sale of comics “dealing with crime or violent death or injury” to anyone younger than eighteen a crime. The proposed law, which included fines of up to $100 for any violators, included a clause stating that it was “specifically…not intended to apply to news accounts or to drawings or photographs used with such articles.” The Arkansas House of Representatives passed it 55–26 on February 22, but it died in the Arkansas Senate on March 3 when it “couldn’t even get a quorum of votes when it came up.”

Ordinance 556 is apparently still on the books in Blytheville in the twenty-first century.

For additional information:

Anderson, George. “Comic (?) Books Replace Humor with Murder, Sex and Violence.” Blytheville Courier News, May 14, 1954, pp. 1, 14.

Bowman, Michael, and Holly Kathleen Hall. “Ordinance 556: The Comic Book Code Comes to Blytheville, Arkansas.” Communication Law Review 14.2 (2014): 1–31. Online at https://commlawreview.org/Archives/CLRv14i2/CLRv14i2_Comic_Book_Bowman_Hall.pdf (accessed December 15, 2022).

“Comic Book Ban Bill Introduced.” Camden News, February 3, 1955, p. 1.

“Council Okays Sewer Work.” Blytheville Courier News, January 19, 1955, p. 1.

“Crime Comic Books Rapped.” Camden News, February 23, 1955, p. 1.

“Council to Get Comics Code.” Blytheville Courier News, November 12, 1954, p. 1.

“Ordinance No. 556.” Blytheville Courier News, January 22, 1955, p. 16.

“Senate Okays Liquor Sales along Border.” Arkansas Democrat, March 3, 1955, p. 1, 2.

“Showdown Near in Comic Book Fight.” Arkansas Democrat, November 14, 1954, p. 6.

Wertham, Frederick. Seduction of the Innocent. New York: Rinehart and Company, Inc., 1954.

Mark K. Christ

Central Arkansas Library System

Business, Commerce, and Industry

Business, Commerce, and Industry Literature and Authors

Literature and Authors World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Comic Book Ban Article

Comic Book Ban Article  Comic Book Ban Article

Comic Book Ban Article  Comic Book Ban Article

Comic Book Ban Article  Seduction of the Innocent

Seduction of the Innocent

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.