calsfoundation@cals.org

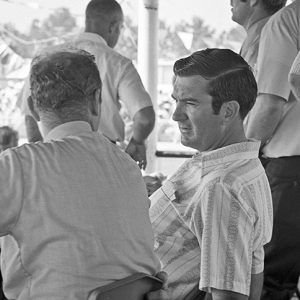

Art Lockhart (1940–)

Alvie L. (Art) Lockhart was as an administrator in the Arkansas prison system for twenty years. He moved to Arkansas in the early 1970s at the behest of Terrell Don Hutto, then head of the Arkansas Department of Correction (ADC). Lockhart worked as the superintendent at Cummins Unit maximum-security prison for ten years before being made head of the ADC in 1981. Lockhart proved a controversial figure and was accused of wrongdoing during the blood plasma scandal. He was forced to resign on May 29, 1992, as he was being investigated for misuse of state funds and fraud.

Art Lockhart was born October 14, 1940, in White Hall (Jefferson County). He later moved to Texas, where he attended high school and college. Lockhart played basketball and football at Hardin High School and was a member of Future Farmers of America (FFA). Standing six feet, six inches tall, he won a basketball scholarship to attend Lon Morris College, where he joined Kappa Alpha fraternity.

Lockhart left school to become a security guard in the Texas prison system. He reentered college at Sam Houston State University, where he studied physical education. He entered a master’s program at Sam Houston for criminology, but it is unclear whether he graduated. Lockhart worked as a warden at “the Walls,” the nickname for the Huntsville Unit in the Texas prison system. There, he met Hutto, who was his supervisor at Huntsville.

In 1971, Lockhart was one of the Texans who joined Hutto in his efforts to reform the Arkansas prison system in the wake of the landmark Holt v. Sarver decision. Hutto appointed Lockhart as the superintendent of Cummins Unit. Hutto and the Texans who joined him made progress in improving the prisons, even though their methods were suspect. For example, they used a disciplinary measure known as “Texas TV” that involved an inmate standing two feet from a wall or fence and leaning his forehead or nose against the wall or fence for extended periods, sometimes for hours. In 1971, Lockhart told a reporter that prisoners were human beings and had to be treated as such. But in January 1973, the Pine Bluff Commercial ran a story concerning accusations that Lockhart had struck and verbally abused inmates. Lockhart denied such wrongdoing. He also denied accusations that he had dropped charges against an inmate in exchange for the prisoner’s positive testimony concerning prison conditions.

Despite continuing controversy at the prisons and in the media, Lockhart’s standing among administrators steadily rose. In 1973, he was considered for the post of head of the notorious Parchman farm in Mississippi, an offer he declined. In 1981, during Frank White‘s term as governor of Arkansas, Lockhart was chosen as the head of the ADC. Lockhart’s appointment came at a watershed time, as he was the first person to be put in charge of the Department of Correction after Judge G. Thomas Eisele ruled—twelve years after the Sarver decision—that the prisons had become compliant with federal standards.

Lockhart was head of the Department of Correction for more than a decade. He also served as president of the Southern States Correctional Association from 1989 to 1990. In 1984, Lockhart said that Arkansas prisons were “a model in the United States.” In spite of such boasting, accusations of misconduct continued to plague him. In 1988, the Board of Corrections ended the practice whereby prison officials had helped themselves to the contents of prison food lockers. With the support of politician Knox Nelson, Lockhart had the practice reinstated. Lockhart was also accused of hitting one inmate, Willie Brown, with the butt of a pistol, in addition to threatening to kill another inmate, James Dean Walker.

A more serious scandal broke in the early 1990s concerning Arkansas’s practice of selling blood donated by prisoners, which was sometimes tainted. In some cases, the blood was given to people who contracted diseases or died from contamination. In addition to selling tainted blood, Lockhart was accused of nepotism when he asked Jimmy Lord—the owner of Pine Bluff Biologicals—to hire his son. The state police also had evidence that Lockhart was personally and illegally taking $200,000 per year from the blood program.

On May 29, 1992, Lockhart resigned his position as head of the ADC following a two-day executive session of the Arkansas Board of Corrections held to investigate the department’s purchases of used equipment. (In November, Roger Endells, a prison administrator from Alaska, was chosen as his replacement.) The Arkansas State Police had compiled a file containing allegations of Lockhart had failed to report income, failed to pay income taxes, and violated state ethics laws, and in July 1992, Gov. Bill Clinton asked that Lockhart’s past purchases also be investigated. After his resignation, Lockhart went to work as the vice president of United States Correction Corp., a private prison company On April 11, 1996, Lockhart was indicted, along with state Representative Lloyd George of Danville (Yell County) and businessman Doug Vess of Dardanelle (Yell County), by a federal grand jury on mail fraud charges. Lockhart subsequently resigned from United States Correction Corp. The federal indictment stemmed from the 1991 purchase by the prison system of a used irrigation system of George’s that was sold to the state through Vess’s company at an inflated price. In August 1997, Lockhart struck a deal with the office of the U.S. attorney to testify against Rep. George in exchange for a dismissal of charges against himself.

During Lockhart’s tenure, Arkansas’s prisons followed national trends toward conservative-based, retributive models of justice and mass incarceration. In the 1980s and 1990s, despite its history as a place of fiscal conservatism—especially when it came to the penitentiary—Arkansas spent hundreds of millions of dollars on new prison construction and administration. The death penalty was also brought back. In June 1990, Arkansas executed its first prisoner since 1964, John Edward Swindler.

After his resignation, Lockhart kept a low profile, living in the Pine Bluff area with his wife, Dorothy.

For additional information:

“Arkansan Considering Post at Parchman Miss., Prison.” Northwest Arkansas Times, August 13, 1973, p. 13.

Crosley, Clyde. Unfolding Misconceptions: The Arkansas State Penitentiary, 1836–1986. Arlington, TX: Liberal Arts Press, 1986.

George, Emmett. “Despite Turbulent Corrections Career, Lockhart Had Powerful Allies.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, April 21, 1996.

Friedlieb, Linda. “Lawmaker Admits Mail Fraud.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, September 3, 1997.

———. “Lockhart Deal Puts Legislator Odd Man Out.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, August 29, 1997.

Jackson, Bruce. Killing Time: Life inside the Arkansas Penitentiary. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977.

“New Cummins Head Seeks Smooth Operation.” Courier News (Blytheville, Arkansas), August 26, 1971, p. 7.

Colin Woodward

Lee Family Digital Archive, Stratford Hall

Cummins Prison Strike of 1974

Cummins Prison Strike of 1974 Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Law

Law Art Lockhart

Art Lockhart  Art Lockhart

Art Lockhart  Art Lockhart

Art Lockhart

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.