calsfoundation@cals.org

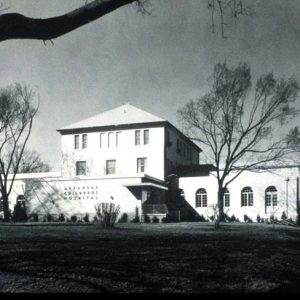

Arkansas Children's Hospital (ACH)

Arkansas Children’s Hospital (ACH), with facilities in Little Rock (Pulaski County) and Springdale (Washington and Benton counties),is the only pediatric hospital in Arkansas and is among the ten largest children’s hospitals in the United States. Pediatric specialists routinely treat patients from other states and occasionally other countries.

Prior to becoming an independent children’s hospital, ACH was an orphanage. In February 1912, Horace Gaines Pugh of Little Rock helped establish the organization that would become Arkansas Children’s Home Society. Pugh, an Illinois native, moved to Little Rock in 1896, where he worked in real estate and eventually opened his own printing house, H. G. Pugh & Company. Pugh’s early mission was to found a haven for children who were orphaned, neglected, or abused. After the early death of his own father, Pugh was forced to abandon his education as a young teenager to support his mother and younger brothers.

During the summer of 1913, the Arkansas Children’s Home Society was moved to Morrilton (Conway County) after Emma Hannaford donated her Victorian home and thirty acres to be used as the children’s home. The home was built by Hannaford’s first husband, the late Dr. W. A. C. Sayle, who practiced medicine in Conway County for more than thirty years. During the first year of operation, 157 children were cared for in the Sayle-Hannaford Memorial Home.

In November 1916, retired Methodist minister Dr. Orlando P. Christian was named superintendent of the society, and the institution relocated to Little Rock. Through real estate purchases and donations, the society began to expand in the area of 9th and Battery streets. The roofline of the original building at 9th and Battery can still be seen in the center of the north side of the hospital, facing Interstate 630.

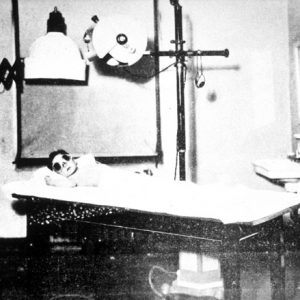

Residents of the orphanage helped break ground for construction of a larger children’s hospital in October 1923. The orphanage was then divided into a girls’ home (the Joseph P. Kendrick Home at 801 Battery) and a boys’ home (the C. A. Forney-Smith Home at Wolfe and Battery). Although construction on the new hospital was complete in November 1924, financial difficulties delayed the opening until March 1926. The opening was met with a great deal of public support, and in three years, the single operating room and two patient beds had expanded to more than fifty patient beds, a laboratory, and radiology and physical therapy departments. In 1929, the Arkansas Children’s Home Society was renamed the Arkansas Children’s Home and Hospital.

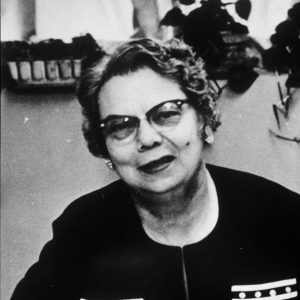

Ruth Olive Beall became superintendent of the hospital in February 1934. She was an integral force of change and growth for the children’s home and hospital, garnering support from President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his wife during their visit to Little Rock for the state’s centennial celebration in 1936.

In 1954, the board of trustees voted to close the orphanage, leaving the care of foster children solely in the hands of state agencies and naming Arkansas Children’s Hospital an independent institution. Twenty-five years later, Robert Cress, president of the hospital board, and Leland McGuiness, chief executive officer of ACH, cut the ribbon on a $1 million expansion that added twenty-four new beds in a new south wing, bringing the total patient bed count to 126. Six months later, in March 1980, Governor Bill Clinton broke ground for a $14 million expansion that doubled the size of the hospital. The new east wing was dedicated in May 1982.

By August 2008, Arkansas Children’s Hospital had grown to a 280-bed facility, the campus of which encompasses twenty-eight city blocks (and additional expansions under way), with a medical staff of approximately 500 physicians and 3,500 total employees. The hospital is recognized internationally for its pediatric Heart Center and heart transplantation program, both of which are among the largest in the country. In 2004, the heart team implanted the second patient in the country with the DeBakey VAD Child, a ventricular assist device (VAD) that helps prolong a patient’s life until a donor heart is available. That same patient became the first child to receive a donor heart after being on the DeBakey VAD Child technology.

In 2005, the heart team implanted the first Berlin Heart pediatric heart pump at ACH and has prolonged the lives of many children with that technology. The year ended with seventeen heart transplants being performed at ACH, tying the facility’s record. In 2006, ACH set a hospital record of 299 open heart procedures, followed by more than 300 open heart procedures the following year.

The hospital celebrated an expansion of pediatric specialty clinics to northwestern Arkansas in May 2007 with the opening of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences/Arkansas Children’s Hospital Centers for Children in Lowell (Benton County). In September 2008, ACH broke ground on a four-story, 258,000-square-foot patient tower, the South Wing, which opened in June 2012.

In 2015, ACH announced plans for a thirty-seven-acre hospital campus in Springdale. The new hospital opened on February 27, 2018. In May 2023, ACH announced plans for a $318 million, eight-year expansion of its hospital in Little Rock and of Arkansas Children’s Hospital Northwest in Springdale. In December 2025, the hospital received its largest donation to date when philanthropist B. Thomas Golisano gave the institution $50 million.

For additional information:

Arkansas Children’s Hospital. http://www.archildrens.org (accessed August 24, 2022).

Hanley, Steven G. A Place of Care, Love and Hope—A History of Arkansas Children’s Hospital. Little Rock: August House, 1994.

Leveritt, Mara. “Miracle on Wolfe Street.” Arkansas Times, March 1990, pp. 30–33, 74–76.

McKay, Serenah. “Expansions Set at Children’s Hospitals.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, May 6, 2023, 1A, 4A. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2023/may/05/arkansas-childrens-hospital-plans-318m-in-expansions-at-little-rock-springdale/ (accessed May 8, 2023).

Ginger Daril

Arkansas Children’s Hospital

I was a patient at ACH for many months at a time from 1942 thru 1954, having contracted the polio virus in the spring of 1942. My favorite memory is the long concrete porch of the hospital where I would sit in my wheelchair for hours.

As a counterpoint to Dr. Burkhead, I’d like to share two positive experiences from after the Atoms for Peace era. Instead of experiencing polio, when I was a little kid my mom fed me some baby Motrin for a fever and I nearly died; my mom was chased by a state trooper on I-630 as she pegged the Blue Torpedo van all the way to the hospital. They saved my life and referred us to Dr. Gene France at Little Rock Allergy and Asthma on W. Markham where nearly thirteen years of allergy shots cured me of all the allergies except drug and nut allergies, and I forget what they said about insect allergies so I keep the knockoff Teva epinephrine around in fewer places relative to my youth.

The second time was after repeated ear infections, the people at Children’s put tubes in my ear and I was afraid of the mask they wanted to put on me and they didn’t retaliate much when my toddler self threw a left hook at the woman because I thought she was trying to make me into Darth Vader. I can still hear just fine and pet fluffy cats as much as I want, and mow my lawn etc. without having to tote an EpiPen everywhere.

Long live Arkansas Children’s Hospital.

After reading about the hospital in this entry, I felt compelled to write about my experiences as a patient in this hospital. I had polio in September, 1951. After leaving the acute-care hospital in Little Rock, I was a patient at the children’s hospital for about six weeks. My stay at this hospital was extremely negative. I received substandard care and also was subject to actual abuse. Parents were allowed to visit only on Sundays. For example, during the week, the nursing staff never combed my hair and seldom bathed me or any of the kids. Before my parents would come on Sunday, the nurses would use alcohol to try to detangle my long hair. Also, when I did not feel that I could eat, they held my nose and forced me to open my mouth to take food. Another child who cried often was locked in the bathroom for hours at a time. I could go on with many examples, but this should make my point.