calsfoundation@cals.org

Smackover (Union County)

| Latitude and Longitude: | 33°21’54″N 092°43’34″W |

| Elevation: | 120 feet |

| Area: | 4.35 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Population: | 1,630 (2020 Census) |

| Incorporation Date: | November 3, 1922 |

Historical Population as per the U.S. Census:

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

– |

– |

2,544 |

2,235 |

2,495 |

2,434 |

2,058 |

2,453 |

2,232 |

2,005 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1,865 |

1,630 |

Smackover’s existence is a result of one of the largest and most dramatic oil discoveries in the nation. Its sixty-eight-square-mile oil field led the nation’s oil output in 1925, with production reaching seventy million barrels. Prior to the discovery of oil, the area’s economy initially relied upon cotton and, by 1890, a timber industry that thrived in the vast virgin forests of southern Arkansas.

European Exploration and Settlement

An uncharted wilderness greeted French hunters and trappers along the Ouachita River. The typography resembled a vast sunken swamp interspersed with rolling hills and steep knolls. The name Bayou de Chemin Couvert (Smackover Creek) first appeared in an April 5, 1789, letter written by the commandant of Fort Miro (Monroe, Louisiana) to the French territorial governor. An expedition led by William Dunbar—a Natchez, Mississippi, planter—and George Hunter—a Philadelphia physician-botanist—explored and mapped the Ouachita River from Monroe to Hot Springs (Garland County) in 1804–1805. The name Smackover is possibly derived from Chemin Couvert (meaning “covered way”), though later histories attribute the name to an eighteenth-century French description of the north and south central areas of Union and Ouachita counties, dubbed “Sumac Couvert,” meaning “covered with sumac”—a reference to the area’s dense growths of sumac trees.

By 1830, settlers holding land grants had migrated to the area. An agrarian economy, bolstered by a single cash crop, cotton, was prevalent until after the Civil War. There were only two large plantations situated within the Smackover area (belonging to the Saxon and Reeves families), with the remaining land utilized exclusively by smaller farms of fewer than 500 acres. As a result, slavery was minimal.

Harsh economic conditions beset the area during and after the Civil War. Although only one major battle was fought in south central Arkansas (the Engagement at Poison Spring), the population experienced extreme difficulties. By 1870, taxation exacted a swift toll. Farms that had been in families for fifty years were sold on the courthouse steps to the highest bidder. Many families that had been solvent only ten years before were destitute.

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

By 1879, the region’s first post office, with the designation Smackover, had opened near a landing on the Ouachita River about five miles north of present-day Smackover. Meanwhile, a new hamlet resulted from railroad construction through southern Arkansas connecting Camden (Ouachita County) and points south to Alexandria, Louisiana. When the railroad survey was completed, it included, almost as an afterthought, a modest layout of a town that included a railhead water stop.

The unincorporated town of fifty residents was named Henderson City in honor of the Alexandria-Camden Railroad Company president, John C. Henderson. The application for a post office was quickly dispatched to Washington DC. Officials learned that Arkansas already had a Henderson post office designation, so the federal government decided to close and move the existing and rarely used Smackover post office located at Newport Landing in Ouachita County. Once the move was completed, the Smackover designation belonged to both a post office and a town.

Early Twentieth Century

By 1908, Sidney Albert Umsted operated a large sawmill and logging venture two miles north of town. He believed that oil lay beneath the earth’s surface in the region. Few paid attention, but Umsted quietly went about buying land and leasing what was not for sale. An economic blockbuster was about to alter the destiny of a town and its people.

On July 1, 1922, Umsted’s wildcat well reached a depth of 2,066 feet. Abruptly, a rumble came from deep beneath the earth’s surface. The crew stepped away, listening. Suddenly, a thick black column of oil burst forth and spurted high above the earth.

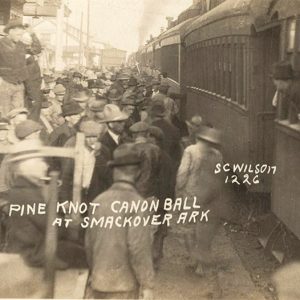

Within six months, 1,000 wells had been drilled, with a success rate of ninety-two percent. The little town had increased from a mere ninety to 25,000, and its uncommon name would quickly attain national attention.

Smackover was officially incorporated on November 3, 1922. Lawlessness was so rampant that, among the twenty-five petitioners on the incorporation document, none was willing to hold public office. Later that month, the town saw a multi-day riot of unbridled violence. The town’s population steadily declined as oil companies and their employees moved away when more lucrative oil discoveries were made in Texas and Oklahoma. About 100 independent oil companies replaced the twelve major petroleum corporations in this period.

Unfortunately, conservation laws to protect the environment were absent in Arkansas, and as a result, wells were allowed to “run wild” until the natural gas had been vented into the atmosphere. This practice eventually ruined the giant oil field, which could be compared to a punctured aerosol can that has half of its contents remaining but no remaining interior pressure to remove it. By the early 1930s, the Smackover oil field’s production had declined dramatically, and the petroleum industry’s attention turned to new discoveries in Texas and Oklahoma. The 1923 population of 25,000 decreased to 2,500.

World War II through the Faubus Era

The town’s economic outlook improved considerably during World War II, when new oil discoveries fueled the area’s four refineries. The war effort created a huge demand for petroleum, and the oil field was the focus of renewed exploration and drilling.

Although the Smackover field is still going strong into the twenty-first century, it has none of the robust vigor that was so prevalent in the 1920s. Its landscape is scarred by oil and saltwater running freely over the earth and into its streams due to the work of the oil industry.

Modern Era

Although the boom days are over, Smackover is still a viable community with a stable population. The petroleum industry still plays an important role in its economy with fifty percent of its population depending upon the oil industry.

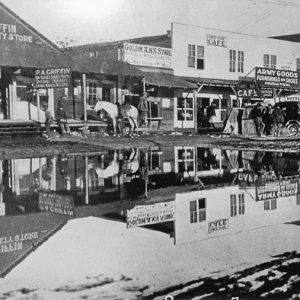

Smackover has experienced numerous improvements through the years, but its main street appears much as it did in the boom days; many of the original brick structures remain. Well-established churches, five city parks, a nature trail, a country club, and unlimited boating, fishing, and hunting opportunities make the town a welcoming community. The Oil Town Festival has been held annually since 1971 with free concerts and free family and children’s activities.

The citizens of Smackover consider their school system to be the town’s most important asset. Since 1995, ninety-five percent of the school’s campus has been replaced with new construction.

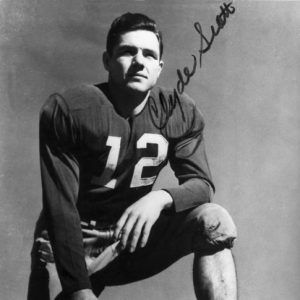

Former Smackover residents of note are Sidney Albert Umsted, who discovered the Smackover oil field, and Clyde “Smackover” Scott, who was an All-American in football and track and field at the University of Arkansas, as well as an Olympic silver medallist.

Smackover was also home to Rhena Salome Miller Meyer, better known as the “Goat Woman,” who lived in Smackover from 1929 until her death in 1988. She was an ex-Barnum and Bailey circus performer who lived with her husband in a circus carriage and raised goats. The Goat Woman’s circus carriage is featured in an exhibit gallery in the Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources, which is located near Smackover.

For additional information:

Andrews, Teresa. “Smackover.” Arkansas Democrat Sunday Magazine, July 13, 1986, pp. 4–5.

Lambert, Don. “A History of Smackover, Arkansas.” Research Library. Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources, Smackover, Arkansas.

Oral History Collection. Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources, Smackover, Arkansas.

Don Lambert

Smackover, Arkansas

Abandoned Smackover Oil Well

Abandoned Smackover Oil Well  Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources

Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources  Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources

Arkansas Museum of Natural Resources  El Dorado Oil Rig

El Dorado Oil Rig  Sleepy LaBeef

Sleepy LaBeef  Oil Field Workers

Oil Field Workers  Oil Field Workers

Oil Field Workers  Oil Storage

Oil Storage  Oil Train

Oil Train  Clyde Scott

Clyde Scott  Smackover Aerial View

Smackover Aerial View  Smackover Aerial View

Smackover Aerial View  Smackover Depot

Smackover Depot  Smackover Field

Smackover Field  Smackover Fire Department

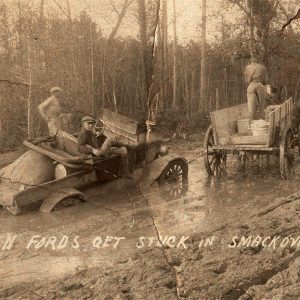

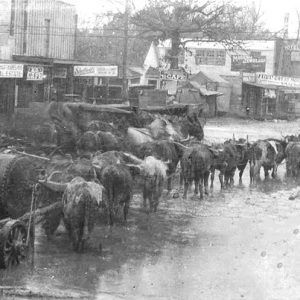

Smackover Fire Department  Smackover Mud

Smackover Mud  Smackover Oil Field

Smackover Oil Field  Smackover Riot Article

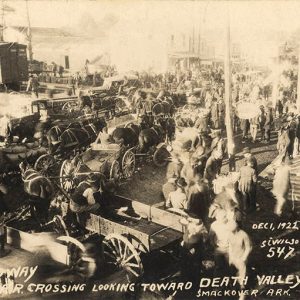

Smackover Riot Article  Smackover Street Scene

Smackover Street Scene  Smackover Street Scene

Smackover Street Scene  Smackover Street Scene

Smackover Street Scene  Smackover Street Scene

Smackover Street Scene  Smackover Street Scene

Smackover Street Scene  Smackover Street Scene

Smackover Street Scene  Sidney Umsted

Sidney Umsted  Union County Map

Union County Map

My granddad, my dad, my mother, and my aunts had mineral rights from the great Smackover oilfield and all decided to move to Shreveport, Louisiana. One of my granddads stayed in Bradley, Arkansas. My entire family never received hardly anything from Texaco for leasing our mineral rights. Ninety years later, Texaco did super great but never paid ONE CENT to my aunts, my uncles, my great-grandparents, my grandparents, my late brother’s family, or me in my life, and I will be sixty-nine years old next month. Texaco should be required to supply copies of all financial records to these leases and be sanctioned to pay their debts as agreed for mineral rights that Texaco may have traded off, sold, etc.

My information comes from my late granddad Bruce Williams, my late parents Jack and Jewel Wedgeworth, my late aunt Christine Williams, and my late oldest brother Willard J. Wedgeworth. The Texaco Lease for Bradley, Arkansas, was filed in the courthouse there. Most of my family moved to Shreveport to never receive their hopes and dreams to help them start a new life in a big city.

Texaco screwed everyone. I have only a small hope that this story can disclose the business ethics and swindle practices of earlier days of Texaco. They shafted a lot of people. I have purchased gasoline from a Texaco station. I have nothing to gain and don’t know anyone employed at Texaco.

I wish to add that the three Burnett brothers–Bill, Bobby, and Tommy–are from Smackover and each of them contributed to the great Razorback football teams of the mid-1960s. Their achievements made all Razorbacks fans proud, especially those of us who were accustomed to seeing the Razorbacks ranked in the top ten nationally every week.