calsfoundation@cals.org

Rockabilly

Rockabilly, a musical genre that appeared in the mid-1950s, is an early form of rock and roll initially performed by white musicians from the mid-South. Several Arkansans became leading rockabilly songwriters and performers.

A distinctly American phenomenon, rockabilly was strongly influenced by developments of the post–World War II period. These include the introduction of the single-play 45 rpm record, the early phases of the civil rights movement, and the increasing mobility and purchasing power of teenagers. Characterized by a blues structure and a moderately fast tempo, rockabilly music celebrated a world of cars, parties, fast living, and sexual relationships. Its use of slang, much of it from African-American origins, and its themes of rebellious youth and self-indulgence, caused disfavor in many conservative groups.

Arkansas musicians had formative influence on the development of rockabilly. They include the jump blues of Louis Jordan, the rhythmic gospel style of “Sister Rosetta” Tharpe, and the hillbilly boogie sound of Wayne Raney. Early references to rockabilly as “hillbilly bop” suggest its origins in country music and western swing, with additional traces of bluegrass and honky-tonk. Arkansas rockabilly artists were influenced by the increasing popularity of radio barn dance shows in the early 1950s. Foremost among these were the Grand Ole Opry from Nashville, Tennessee, and the Louisiana Hayride from Shreveport, Louisiana. These broadcasts were emulated in Little Rock (Pulaski County) with the Barnyard Frolics, a live performance venue for local talent and regional performers.

Rockabilly was also strongly influenced by rhythm and blues and the evolution of acoustic country blues into the new, up-tempo electrified style of Howlin’ Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, Robert Lockwood Jr., and other early stars of the King Biscuit Time radio show from Helena (Phillips County).

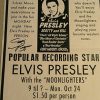

These varied influences reflect the major demographic and economic changes of the postwar period, a time when large populations of rural black southerners relocated to northern cities. The typical rockabilly artist reflected those significant changes. He was born in early 1930s, came from a middle or lower economic class, and by the mid-1950s was working in a trade or blue-collar job. Arkansans with rural backgrounds who had known the harsh realities of tenant farming and picking cotton were common in this group. They were keenly aware of the popularity and success of Elvis Presley, whose touring schedule included more than three dozen Arkansas shows in 1954 and 1955.

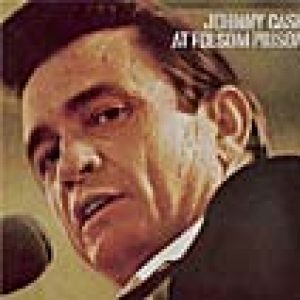

Many Arkansas musicians who transitioned to other styles began their careers in the rockabilly mode, including Johnny Cash, Conway Twitty, Levon Helm, Narvel Felts, and Sleepy LaBeef. Other Arkansans, such as Sonny Burgess, Billy Lee Riley, and Ronnie Hawkins, stayed closer to their original rockabilly sound over the decades. Numerous other Arkansas musicians performed and recorded rockabilly with limited recognition outside their musical communities.

Rockabilly music was played at bars, clubs, honky-tonks, college fraternity parties, and dance halls—places where people could dance and drink with some abandon. Some establishments were small, rough country venues where farmers in bib overalls arrived on tractors, seeking evenings of excessive drinking, fighting, and flirtation. Other clubs, such as Beverly Gardens in Little Rock, could accommodate 200 to 300 people. The largest club in Arkansas at this time was the Silver Moon in Newport (Jackson County), which could seat more than 800 people.

While rockabilly music owes much of its sound and character to the blues, Arkansas law and custom in the 1950s prohibited integrated social encounters, particularly where dancing occurred. Black musicians performed at clubs where rockabilly was played, and integrated bands were not uncommon, but black Arkansans seldom attended these clubs as patrons.

At the height of the rockabilly era in the late 1950s, many Arkansas rockabilly groups, such as Sonny Burgess and the Pacers and Billy Lee Riley and the Little Green Men, had recorded for Sun Records and were rising to national attention. Dale Hawkins, a member of the Rockabilly Hall of Fame, specialized in creating a sound (called “Swamp Rock” by some) that went on to help shape rock and roll music. Bobby Brown of Olyphant (Jackson County) was a popular rockabilly performer of the 1950s and 1960s, often playing at the Cotton Club in Trumann (Poinsett County). On May 13, 1957, the Little Rock television affiliate of CBS began broadcasting Steve’s Show, hosted by Steve Stephens and featuring local teenagers who danced to hit records as rockabilly artists and other performers lip-synched the words.

The rockabilly era ended with the decade, with several of its national stars in new engagements. Sonny Burgess’s “Sadie’s Back in Town,” released by Sun Records on December 31, 1959, could be considered the last rockabilly hit of the era. The popular music industry was shifting to a softer format and more banal subject matter than rockabilly’s fast cars, rowdy women, and rebellious partying. Arkansas rockabilly artists either modified their styles or retired from the music business. A rockabilly revival in the 1970s brought renewed attention to the genre, while European audiences have maintained a nearly cult-like devotion to the original sound. Younger Arkansans, such as Jason D. Williams of El Dorado (Union County), continue to perform in a traditional rockabilly mode.

For additional information:

Altschuler, Glenn. “All Shook Up”: How Rock ‘n’ Roll Changed America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Burke, Ken, and Dan Griffin. The Blue Moon Boys: The Story of Elvis Presley’s Band. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2006.

Cochran, Robert. Our Own Sweet Sounds: A Celebration of Popular Music in Arkansas. 2nd ed. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

Dregni, Michael. Rockabilly: The Twang Heard ’Round the World—An Illustrated History. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press, 2011.

Marcus, Greil. Mystery Train: Images of America in Rock ‘n’ Roll Music. New York: Plume, 1997.

McNutt, Randy. We Wanna Boogie: An Illustrated History of the American Rockabilly Movement. Fairfield, OH: HHP Books, 1988.

Morrison, Craig. Go Cat Go: Rockabilly Music and Its Makers. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1996.

Schwartz, Marvin. We Wanna Boogie: The Rockabilly Roots of Sonny Burgess and the Pacers. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2014.

Toches, Nick. Country: The Twisted Roots of Rock ‘n’ Roll. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 1996.

Marvin Schwartz

Little Rock, Arkansas

"Folsom Prison Blues," Performed by Johnny Cash

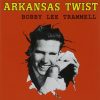

"Folsom Prison Blues," Performed by Johnny Cash  Dale Hawkins

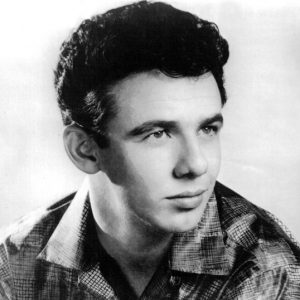

Dale Hawkins  Sleepy LaBeef

Sleepy LaBeef  "Radioland," Performed by the Cate Brothers Band

"Radioland," Performed by the Cate Brothers Band  "Red Headed Woman," Performed by Sonny Burgess

"Red Headed Woman," Performed by Sonny Burgess  Rockabilly Exhibit

Rockabilly Exhibit

My father was Gilbert Brewington. His band was Gib Brewington & the Thunderbirds. Gib played local clubs and venues around the Jonesboro area. I have some cool announcements from the Jonesboro Sun that I can download.

The band played the Strand Theater as well as the Pavilion at Walcott. Billy Lee Riley was a close friend of our family.

My father’s life was cut short in 1958 when he was hit by a train on the ASU tracks. My father always had a smile on his face. He was a wonderful man who left two little daughters-Melody and Teresa-and son Lynn.

Gib would be happy to know that two of his grandchildren graduated with music degrees.