calsfoundation@cals.org

Ouachita Baptist University (OBU)

Ouachita Baptist University (OBU) is an independent, residential institution in the liberal arts tradition associated with the Arkansas Baptist State Convention. Founded on April 8, 1886, it capped longstanding Arkansas Baptist interest in making higher learning more readily available to more people, in providing an educated ministry and educated lay leadership, in strengthening denominational loyalty, and in extending denominational influence. It gained university status in 1965 and has been rated by US News and World Report as the “No. 1 Baccalaureate College in the South” and included in its list of “Great Schools, Great Prices.” In 2013, it offered sixty-one degree options in eight schools within the university, and its mission statement proclaimed it “a Christ-centered learning community. Embracing the liberal arts tradition, the university prepares individuals for ongoing intellectual and spiritual growth, lives of meaningful work, and reasoned engagement with the world.”

The Conger Era

Samuel Stevenson and James M. Gilkey established the first in a string of Baptist schools (and the state’s first Baptist school) in Arkadelphia (Clark County); it and the Arkansas Institute for the Blind preceded the Civil War, followed by the Arkadelphia Baptist High School (later Red River Baptist Academy). Ouachita Baptist College (OBC) was the first of four institutions of higher education (two for whites and two for blacks) begun between 1886 and 1896 in a town that locals liked to promote as “The Athens of Arkansas” and “The City of Colleges.”

OBC was advertised as an institution created not “as a financial speculation, but solely upon an educational basis.” Free tuition for all ministers “irrespective of denomination” (until 1937), a tuition waiver for ministers’ children, and another for siblings simultaneously at school exacerbated the financial situation and led one historian to estimate that more than a third of OBC students between 1886 and 1933 paid no tuition at all.

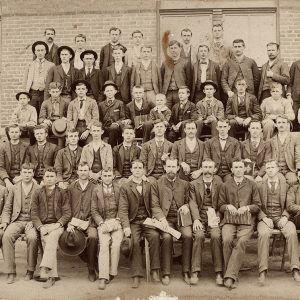

Arkadelphia citizens put up thirteen acres of land, a building, and $10,000 for the privilege of having the school and sited the college in the old Arkansas Institute for the Blind building on a bluff overlooking the Ouachita River to its east. Founding president John William Conger and his wife made up a third of the initial faculty. OBC began with instruction at all levels—primary, preparatory, and collegiate, though the primary disappeared by about 1900. Enrollment grew from the original 166 to averaging in the 300s under Conger, and the school maintained a low teacher-student ratio, eighteen to one in 1907. Initially, women lived on campus while men boarded in town. Student life centered on literary clubs (two for females and two for males), while sports stirred deep passions: the hotly contested “Battle of the Ravine” with cross-street rival Henderson-Brown College began in 1907, making it one of the nation’s oldest college football rivalries. The curriculum, standard for colleges of its day, contained a few surprises (like bookkeeping) and featured compulsory military training consistently until 1991.

1910 to 1950

Continuing financial difficulties led Arkadelphia citizens to pay the institution’s debt in 1914 and again in 1936 in return for the promise to keep OBC in Arkadelphia permanently. Presidents and supporters began endowment drives several times, but the institution accumulated little until World War I. Since 1925, the institution has been a regular part of the Arkansas Baptist State Convention annual budget, which has helped stabilize its finances.

Being included in the state convention’s budget came at a price, one which demonstrated the tension between convention and school over academic freedom on the issue of evolution. In 1924, the Arkansas State Baptist Convention adopted an anti-evolution statement stronger than that previously adopted by the Southern Baptist Convention in 1923, which held that “loyalty to fact is a common ground of genuine science and the Christian religion.” The State Convention also required all employees to sign this statement. The man who guided OBC through this clash between Christian fundamentalism and modern science, Dr. Charles Ernest Dicken, informed OBC trustees that he and every faculty member would sign the SBC statement, which initially satisfied the trustees. At a called meeting that roughly coincided with John T. Scopes’s arrest in Tennessee, the trustees rescinded their earlier position and found only the fundamentalist statement acceptable. Dicken consequently resigned, effective June 1, 1926. Seven of the twenty-four faculty members also refused to sign the anti-evolution statement, and all seven forfeited employment. Twelve signed with a caveat; only five signed outright. One trustee observed that the convention’s action would keep the school from hiring “the highest type of educator”—a fear borne out as the school endured three new presidents over the next seven years.

OBC hired its first PhD holder in 1913, and that chemist began a tradition of terminal-degree-holders teaching science. In 1921, the institution began encouraging faculty without terminal degrees to pursue them and hired its first woman PhD holder in 1929 (in mathematics).

Associations that were formed through Baptist mission work, particularly that done by graduates, attracted international students from Latin America, Africa, and Asia, starting with Charles Pong (1922–1926). Enrollment averaged about 300 until better financial times; the college’s financial status improved under the leadership of James Richard (J. R.) Grant, and the GI Bill helped swell enrollment to average in the 500s after World War II. Literary clubs were replaced by social clubs and the beginning of national honor societies: general national honor society Scholarship Society of the South (1928), today Alpha Chi, as well as discipline-specific honor societies in debate (1924), English (1931), and drama (1931). The Preparatory Department disappeared by World War I, as did an early MA program in all disciplines. The military training program expanded with the advent of the Students’ Army Training Corps during World War II and the Reserve Officer Training Corps program (now joint with Henderson State University) in 1919, with such success that an Army article dubbed OBC the “West Point of the Ozarks.” During World War II, the institution housed the Sixty-Seventh College Training Detachment Aircrew. The college achieved accreditation for the first time in 1928 and standardized its curricular structure in the 1940s.

1950 to 1970

The postwar economic boom and Great Society spending on higher education provided growth and relief to the financial picture and led to expansion in OBC’s size and programs, primarily under the leadership of President Ralph Phelps. Enrollment averaged about 1,300 during the 1950s and 1960s (when it reached its greatest enrollment ever: 1,881 students in 1966). In 1962, the college admitted as its first black students Rhodesians Michael and Mary Makosholo. Two years later, the trustees opened admission to all persons “regardless of race, creed, color, or national origin.” That fall, Carolyn Jean Green became the first African American to enroll under the new policy.

National honor societies in the sciences appeared during the 1950s. In 1959, the institution added a graduate program in history and religion, which narrowed solely to education after a few years (abandoned in 1991), and a nursing school in 1965 (abandoned two years later), which provided justification for assuming university status. Holders of PhD degrees became vital when North Central Association pressed for terminal degrees in all fields, and the institution’s success allowed it to sustain accreditation after 1953, at which time ninety-six percent of students were Baptist and eighty percent from Arkansas.

1970 through Present

Although the school remained tuition-driven, it posted large endowment gains. Through gifts and purchases, campus extended northward along the river until it encompassed more than 200 acres. Over time, campus accumulated a variety of buildings, including former residences and barracks and other World War II–era structures in a hodgepodge of sizes and styles. In the early 1970s, the school developed a plan to provide a unified architectural style and to envision campus growth. However, renovating and retrofitting the institution’s first free-standing library building (built in 1949, renovated and expanded in 1987)—as well as transforming the oldest remaining campus building, former women’s dormitory Cone Bottoms (built in 1923), into an administration building in 1994—departed from the plan. Initially, the institution named buildings to honor exemplary service; more recently, building names generally honored significant donors. In 2008, nine buildings housed all on-campus academic activities. In 2014, OBU dedicated a new football stadium, the Cliff Harris Stadium, and broke ground on the Ben M. Elrod Center for Family and Community.

OBU has invested heavily in permanent faculty with terminal degrees but increasingly relied on adjunct faculty over the last two decades, in keeping with national trends. Although adjuncts teach in many fields, certain departments have come to rely heavily on adjunct faculty for specialized and low-demand courses. OBU still maintains a low teacher-student ratio: thirteen to one in 2008.

Enrollment has averaged in the mid-1,500s since 1970 and displayed increasing diversity: in 2013, seventy-three percent were Baptist and sixty-one percent from Arkansas. Since 1970, the range of countries represented on campus has broadened, in part because of international recruiting and scholarships in the minor sports. International students averaged forty-one during the early 1990s, 100 during the latter 1990s, and sixty-one since then. OBU has also traditionally enrolled the second-largest number of “missionary kids” among Southern Baptist schools, so that, in 2013, students represented about thirty-four countries. In 2019, students represented thirty countries.

Ending the graduate program in 1991 focused the school on the liberal arts tradition. The curricular structure, revised during the 1980s, retains the standardization of the 1940s but adds courses and programs to keep pace with educational changes. The international studies program offered opportunities in fourteen countries in 2013, and the library’s Special Collections is the repository for Arkansas Baptist State Convention records, a significant collection of political papers, and a significant oral history collection. Dr. Ben Sells became president of OBU in 2016. Total enrollment in fall 2020 was 1,704, across sixty undergraduate programs, and OBU had more than forty student clubs and organizations, as well as fifteen NCAA Division II sports. By fall 2023, the student body had risen to 1,815, and the school had more than fifty clubs and played eighteen Division II sports. In 2020, OBU began launching graduate programs, mostly online, and by 2024, it offered master’s degrees in nutrition and dietetic internship, exercise science, applied behavior analysis, business administration, counseling, and curriculum and instruction.

For additional information:

Arrington, Michael E. Ouachita Baptist University: The First Hundred Years. Little Rock: August House Publishers, 1985.

Bagley, Andrew. “A Study of Early Arkansas Baptist Education: The Founding of Ouachita College.” Clark County Historical Journal (1999): 127–133.

Brawner, Steve. “The Tigers Have the State by the Tail.” Arkansas Times, October 5, 2001, pp. 10–13.

Ouachita Baptist University. http://www.obu.edu (accessed September 13, 2024).

Richter, Wendy, ed. Clark County Arkansas: Past and Present. Arkadelphia, AR: Clark County Historical Association, 1992.

Simmons, Jake. “Ouachita Baptist University: In the Beginning.” Clark County Historical Journal (2004): 97–106.

S. Ray Granade

Ouachita Baptist University

Arkansas' Independent Colleges and Universities

Arkansas' Independent Colleges and Universities Bailey, O. C.

Bailey, O. C. Benson, Jesse N. "Buddy"

Benson, Jesse N. "Buddy" Elrod, Ben

Elrod, Ben Grant, Daniel Ross

Grant, Daniel Ross Holloway, William Judson

Holloway, William Judson McBeth, William Francis

McBeth, William Francis Riley, Bob Cowley

Riley, Bob Cowley Berry Chapel

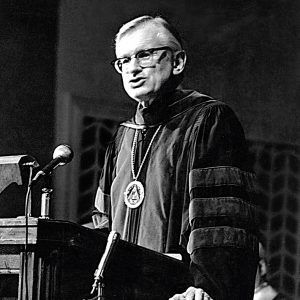

Berry Chapel  Grant Speaking

Grant Speaking  J. R Grant Memorial Hall

J. R Grant Memorial Hall  "The Great Divide," Performed by Point of Grace

"The Great Divide," Performed by Point of Grace  Carolyn Jean Green

Carolyn Jean Green  Joe Nix

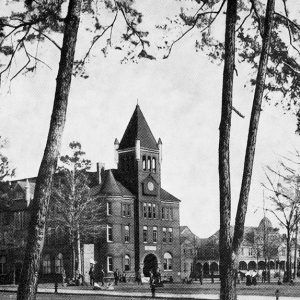

Joe Nix  Ouachita Baptist College Chapel

Ouachita Baptist College Chapel  Ouachita Baptist University

Ouachita Baptist University  Ouachita Baptist College

Ouachita Baptist College  Ouachita College

Ouachita College  Ouachita College Mascot

Ouachita College Mascot  Ouachita Preparatory Academy

Ouachita Preparatory Academy

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.