calsfoundation@cals.org

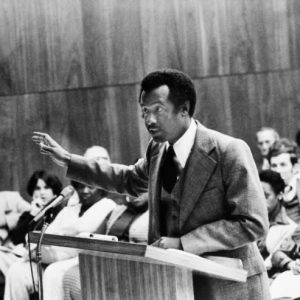

John Winfred Walker (1937–2019)

John Winfred Walker was a lawyer who emerged from segregated schools and society in southwestern Arkansas to wage a sixty-year war on discrimination in Arkansas’s education systems, public institutions, and workforce. Walker’s name became synonymous with civil rights in Arkansas after the initial legal battle from 1957 to 1959 to desegregate Central High School in Little Rock (Pulaski County). Once out of Yale University’s law school in 1964, Walker took over the long-running school-integration lawsuit in Little Rock and also filed scores of lawsuits in federal courts to force recalcitrant school districts across Arkansas to put black and white children in the same classrooms or coequal learning environments. Other suits by Walker and his young partners in one of the first racially integrated law firms in the South attacked job discrimination at major corporations in the state, nearly always successfully. All the lawsuits and Walker’s persistence and near omnipresence in the news during more than two decades of racial strife earned him the enmity of much of the state. When Governor Winthrop Rockefeller appointed Walker in 1970 to the state Board of Education—no African American had ever held the position—the Arkansas Senate refused to confirm him, a highly unusual step. Late in life, he turned to politics and was elected to five terms in the Arkansas House of Representatives.

John Walker was born on June 3, 1937, in Hope (Hempstead County), the son of John Wesley Walker Jr., who was a handyman, and Virginia Walker. Walker was the oldest of five children; only one, Marva Walker Smith, survived him. His great-uncle, Dr. Lawrence A. Nixon, a physician in eastern Texas, was famous as the plaintiff in two voting-rights cases, Nixon v. Herndon (1927) and Nixon v. Condon (1932), in which the U.S. Supreme Court struck down state laws that barred or limited black voting in Texas primaries. Nixon fled to El Paso to escape threats to his family. Nixon’s sister married Walker’s grandfather, and the couple moved to Hope and taught in the town’s black schools.

He attended the Henry Clay Yerger High School at Hope, one of the rare schools in rural Arkansas that provided a high school curriculum to black children. Walker would later say that the school where his grandparents had taught prepared the students well, emphasizing that black children were not inferior and stressing the importance of voting and asserting their rights. Although his parents were poorly educated, Walker wanted a first-rate education and to be a petroleum engineer. His family moved to Houston, Texas, in 1952. He graduated from Jack Yates High School, an all-black school, in 1954.

Walker applied to the University of Texas at Austin and was accepted as one of the first six black undergraduates to be admitted, but on registration day the university announced that none of them would be admitted after all. In a lawsuit arising from the school’s denial of the admissions, a confidential letter from the university’s registrar to the dean of admissions, which was introduced into evidence, suggested a plan that would “keep Negroes out of most classes where there are a large number of girls,” which proved that Walker was denied admission because he was black. He was required to first take at least two years of classes at one of the state colleges for African Americans, Prairie View A&M College or Texas Southern University, before he could be considered for admission to the University of Texas. The unsuccessful lawsuit cost him all his savings, so he could not enroll at Howard University in Washington DC, which had admitted him. He enrolled at Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical, and Normal College in Pine Bluff (now the University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff), the Arkansas state school for African Americans.

The incident changed Walker’s ambition from engineering to law and education. He graduated from Arkansas AM&N with a degree in sociology in 1958. He received a master’s degree in education at New York University in New York City and a law degree, in 1964, from Yale University. Walker married Gloria Blakemore of Nashville, Tennessee, and they had two sons and three daughters.

While he was a student at Arkansas AM&N, Walker was attracted to the legal battles over school integration at Hoxie (Lawrence County) and Little Rock, and he associated with the Arkansas Council on Human Relations, an organization striving to promote integration and racial dialogue. When Governor Orval E. Faubus sent the Arkansas National Guard to block the entrance of nine black children at Central High School in September 1957, Walker wrote an editorial condemning it in the college newspaper and organized a protest at the whites-only public swimming pool at Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) in hopes of a mass arrest. Only one person joined him, and he could not get arrested.

He worked part time at the Council on Human Relations at Little Rock with Nat Griswold (director), Ozell Sutton, and several of its board members, including Fred K. Darragh. They encouraged him to enter graduate school at New York University and then to enroll in the Yale law school. After getting a law degree, Walker returned to Little Rock to practice civil-rights law. His first work was as a cooperating attorney with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Legal Defense Fund in New York City. In 1968, with Norman Chachkin, he established one of the first racially integrated law firms in the South. With Chachkin and other young lawyers—Buddy Rotenberry, Philip Kaplan, Jack Lavey, Perlesta Hollingsworth, Richard Mays, Frank Newell, John Bilheimer, and Janet Pulliam—who joined him in the firm in the late 1960s and 1970s, Walker and his partners represented young African Americans or sympathetic whites who got arrested for actions such as picketing businesses that discriminated against blacks, marching, sitting in at lunch counters, distributing literature on a state college campus, trying to swim in a public pool, trying to ride a commercial bus, getting fired for exercising free-speech rights on a state college faculty, and trying to eat lunch at the cafeteria in the Arkansas State Capitol, which the government had turned into a private club to deny service to black patrons.

But the bulk of his work, at least that which brought him fame and notoriety, was with the schools, starting with the Little Rock school case (Aaron v. Cooper), which was originally filed by Wiley Branton of Pine Bluff and the Legal Defense Fund, represented by Thurgood Marshall, later a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Walker picked up the case after opening his law office in 1965. In 1966, he and the Legal Defense Fund filed a fresh suit against the school district for the parents of five black children (Clark v. Board of Education) challenging one of the successive plans called “freedom of choice” designed to diminish integration. That suit and his representation of “the Joshua intervenors”—Lorene Joshua had children in the schools—and others continued the legal battle for the next fifty years. Walker objected that every mutation of the school district’s and the state’s desegregation efforts (the state government entered the long-running dispute in 1982 in a suit filed by the Little Rock School District seeking consolidation with the two adjoining school districts in Pulaski County) fell short of providing black children the equal education that they deserved and the law required.

Walker and his associates filed similar suits against the other Pulaski County school districts (North Little Rock and Pulaski County Special School District) and against schools across eastern and southern Arkansas that were holding back from desegregating their classes or using schemes like the state’s “pupil-assignment” and “freedom-of-choice” laws to dilute integration. The federal courts, particularly the Eighth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, were nearly always sympathetic to Walker’s complaints.

Other suits sought to overcome job discrimination in large businesses. Walker and his partners sued two paper-company giants, International Paper Company and Georgia-Pacific Corporation, for violating Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by discriminating against African Americans in hiring and promotions at their plants at Pine Bluff and Crossett (Ashley County). They prevailed in both cases (Rogers, et al. v. International Paper Company, 1975, and Powell, et al. v. Georgia-Pacific Corporation, 1982) at the Eighth U.S. District Court of Appeals. Both suits accused the companies and the unions that represented their production workers of hiring African Americans only for the dirtiest, hottest, and lowest-paying jobs that no one else would do and never promoting them.

Walker was notorious in the legal fraternity for his very casual preparation for trials. He apparently knew that he had the law on his side, so he just improvised in the courtroom. At the Georgia-Pacific trial at El Dorado (Union County), the corporation’s law team from Little Rock had prepared elaborately and Walker hardly at all. Walker politely needled the company’s personnel staff on cross-examination, destroying the company’s case. The presiding judge, the conservative and segregationist former congressman Oren Harris, ruled decisively for the black employees, and so did the Court of Appeals. Walker later won an employment-discrimination suit against the retail giant Walmart over discrimination against black truck drivers (Nelson v. Wal-Mart Stores Inc., 2009).

Even the athletic program at the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County) was not outside Walker’s target range. He unsuccessfully sued to get three black football players who were suspended by coach Lou Holtz reinstated for the 1978 Orange Bowl and sued, again unsuccessfully, to get Nolan Richardson reinstated as the basketball coach of the Razorbacks in 2002 after athletic director Frank Broyles persuaded the chancellor to fire the coach, who had complained about racial discrimination.

Walker ran for a seat in the Arkansas House of Representatives in 2002 and was defeated; he ran again in 2010 and was elected and then re-elected repeatedly. He ran promising to “open doors and widen opportunities” for all the people left behind. Although he often lectured his colleagues on the Constitution and the rights it guaranteed, the majority of lawmakers, who disagreed with him fundamentally, found him collegial, amiable, and witty, and the resentment that initially greeted him dissolved. He received numerous awards from bar organizations and the American Civil Liberties Union and was inducted into the Arkansas Black Hall of Fame.

Walker, who suffered from lung cancer, died on October 28, 2019. His body lay in state in the state capitol rotunda. He is interred in the Cane Hill Cemetery in Hempstead County.

For additional information:

Besson, Eric, Hunter Field, and John Moritz. “Walker, a Civil-Rights Pioneer as Lawyer, Lawmaker Dies at 82.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 29, 2019, pp. 1A, 4A.

Brantley, Max. “Civil Rights Giant John Walker Has Died at 82.” Arkansas Times, October 28, 2019. https://arktimes.com/arkansas-blog/2019/10/28/civil-rights-giant-john-walker-has-died-at-82 (accessed April 20, 2022).

Brummett, John. “Walker Cut No Slack.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, October 29, 2019, p. 5B.

Cottingham, Jan. “John Walker: A Legendary ‘Agent of Change.’” Arkansas Times, June 30, 2000, pp. 14, 16.

Hofheimer, John. “Walker Left Deep Mark Here.” The Leader, November 2, 2019, pp. 1, 5.

John Walker Interview. Butler Center Oral History Collection. https://arstudies.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15728coll5/id/2437/rec/2 (accessed April 20, 2022).

Martin, Richard. “Walker vs. the World.” Arkansas Times, April 22, 1993, pp. 14–15.

Schnedler, Jack. “John Winfred Walker.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, March 19, 2000, p. 1D.

Vinzant, David Gene. “Little Rock’s Long Crisis: Schools and Race in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1863–2009.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2010.

Ernest Dumas

Arkansas Times

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.