calsfoundation@cals.org

Sit-ins

In Arkansas, the “sit-in” protest was used most commonly during the 1960s in association with the civil rights movement as a way to protest segregation at lunch counters, department stores, and other public facilities. The power of the sit-in protest lay in its peaceful nature on the side of the protestors and its ability to apply economic pressure to targeted businesses.

Sit-ins are a nonviolent direct-action protest tactic. Protestors at sit-ins occupied places in both public and private accommodations to put pressure on proprietors to enforce segregation laws. In doing so, those laws—applied to peaceful demonstrators who were simply seeking services provided to other customers—came under intense scrutiny. Sit-ins also disrupted commerce and thereby placed economic pressure on merchants for change. Often, sit-ins were accompanied by economic boycotts of businesses.

Although the civil rights movement of the 1960s popularized sit-in demonstrations, the tactic has a long history. Sit-ins are related to the sit-down strikes used by workers in the United States and Europe in the early part of the twentieth century to halt production and place pressure on business owners to meet their demands. One of the most famous of these was the Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1936–1937 staged by the United Auto Workers (UAW) union in Michigan. Mohandas Gandhi also used sit-ins as a tool of protest in South Africa and India.

Civil rights organizations used sit-ins in the United States before 1960, notably the Congress of Racial Equality, which held sit-ins at lunch counters in Chicago, Illinois, in 1942. Other lunch counter sit-ins took place in Kansas and Oklahoma in 1958.

However, sit-ins only became widespread after February 1, 1960, when four African-American students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro sat-in at their local F. W. Woolworth’s lunch counter. Their actions snowballed as other students began sit-ins, first in Greensboro, then in neighboring towns and cities, then all across the South. Within a year, more than 100 cities had experienced sit-ins, with at least 50,000 participants and 3,000 arrests. A number of businesses in Upper South states made the decision to desegregate facilities voluntarily rather than face continued disruption. In April 1960, leaders of the new student sit-in movement met at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, to found a new civil rights organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), to help orchestrate more sit-ins.

The first sit-in in Arkansas took place in Little Rock (Pulaski County) at 11:00 a.m. on March 10, 1960, when around fifty Philander Smith College students marched from campus to the F. W. Woolworth’s store on 4th and Main streets and asked for service at its segregated lunch counter. The students had been in touch with regional SNCC leaders and had attended meetings for training in nonviolence. Most left when asked to do so by the store manager and city police, but the five who did not—Charles Parker (age twenty-two), Frank James (twenty-one), Vernon Mott (nineteen), Eldridge Davis (nineteen), and Chester Briggs (eighteen)—were all arrested. The local Little Rock branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) bailed them out of jail.

On March 17, the five students appeared for trial at Little Rock’s Municipal Court. Judge Quinn Glover found the students guilty under Arkansas Act 226 of 1959 that prohibited “any person from creating a disturbance or breach of the peace in any public place of business.” Glover handed each student a $250 fine and a thirty-day jail sentence, both of which were doubled on appeal on April 27.

On April 12, ten students sat-in at the McClellan, Woolworth, Blass, and Pfeifer Brothers stores on Main Street. The next day, April 13, a group of six students held another sit-in at Pfeifers’ department store. In a separate incident, two students—Thomas B. Robinson (twenty) and Frank James Lupper (nineteen)—requested service at Blass’s lunch counter. When they refused to leave the premises, they were charged under Act 226 of 1959 but also, fatefully, under Arkansas Act 14, which allowed for the arrest of any person refusing to leave a business’s premises when so requested by the manager or owner thereof.

All of the students met with harsh fines and stiff prison sentences, which tied up their cases in the courts on appeal. This factor, and the approaching summer break, brought the sit-in movement in Little Rock to a halt. The movement was briefly revived later in the year, but protestors again met with the same fines and sentences that had stymied earlier demonstrators. Other sporadic attempts to revive the sit-ins failed.

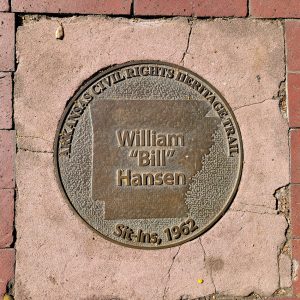

The sit-in movement in Little Rock did not begin again in earnest until October 1962 when, at the request of the Arkansas Council on Human Relations, SNCC sent Bill Hansen (twenty-three) to Little Rock. White SNCC worker Hansen was already a seasoned activist who had previously participated in Freedom Rides and sit-ins elsewhere, as well as in demonstrations in Albany, Georgia, earlier that year. He therefore brought with him an expertise in nonviolent direct action that allowed him to train others in the use of this technique.

Hansen joined with Philander Smith students to run some provisional sit-ins to gauge community reaction. However, store managers still refused to budge. On November 7, students staged a sit-in at the downtown Woolworth’s lunch counter. Hansen called newspapers, television stations, and radio stations to publicize the event as a way of bringing further pressure on the business community to meet the students’ demands.

This time, the sit-ins had the intended impact. Shortly after the outbreak of new demonstrations, prominent local businessmen formed a Downtown Negotiating Committee (DNC), headed by James Penick, president of Worthen Bank and Trust Company. During the following two weeks, a delegation from the African-American community met with the DNC to discuss the practicalities of desegregation. After more sit-ins followed, business leaders agreed to a phased program of downtown desegregation beginning in January 1963. SNCC exported sit-ins around the state as it expanded activities in areas such as Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Gould (Lincoln County), Forrest City (St. Francis County), and West Helena (Phillips County), among others. The use of sit-ins in the civil rights movement across the state became widespread.

One of the lasting legacies of the sit-ins in Little Rock was in the courts. The Little Rock sit-in cases of Frank James Lupper and Thomas B. Robinson were, along with the case of Arthur Hamm in South Carolina, the first sit-in cases to be heard by the U.S. Supreme Court after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed racial discrimination in public accommodations and facilities. The Court dismissed their cases and threw out more than 3,000 other similar cases pending before the courts.

For additional information:

Barnard, Ninfa O. “Courage in PB Sit-Ins a Civil-Rights Moment.” Pine Bluff Commercial, February 14, 2022, pp. 1, 3. Online at https://www.arkansasonline.com/news/2022/feb/14/courage-in-pine-bluff-sit-ins-a-chapter-in-civil/ (accessed February 14, 2022); reprinted as “Pine Bluff’s 1863 Student Sit-Ins at Woolworth’s and McDonalds.” Jefferson County Historical Quarterly 51 (Spring 2023): 31–33.

Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981.

Chafe, William H. Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina and the Black Struggle For Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Hogan, Wesley C. Many Minds, One Heart: SNCC’s Dream of a New America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Kirk, John A. Beyond Little Rock: The Origins and Legacies of the Central High Crisis. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2007.

———. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

———. “Sitting in for Rights.” Arkansas Times, February 1, 2012, pp. 14–17. Online at http://www.arktimes.com/arkansas/sitting-in-for-rights/Content?oid=2045790 (accessed January 24, 2022).

McGee, Holly Y. “‘It Was the Wrong Time, and They Just Weren’t Ready’: Direct-Action Protest in Pine Bluff, 1963.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Spring 2007): 18–42.

Morris, Aldon D. The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement: Black Communities Organizing for Change. New York: Free Press, 1984.

Wallach, Jennifer Jensen, and John A. Kirk, eds. Arsnick: The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2011.

Zinn, Howard. SNCC: The New Abolitionists. Boston: Beacon Press, 1965.

John A. Kirk

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.