calsfoundation@cals.org

James Douglas "Justice Jim" Johnson (1924–2010)

James Douglas “Justice Jim” Johnson served as an Arkansas state senator and an associate justice on the Arkansas Supreme Court in the 1950s and 1960s. He was an outspoken segregationist and ran unsuccessfully against Orval Faubus for governor in 1956. In the 1966 race for Arkansas governor, he became the first Democrat since Reconstruction to lose to a Republican. Johnson helped to make school desegregation a major political issue in the state by protesting the integration of the Hoxie School District in Hoxie (Lawrence County), as well as by working to get an anti-federalist amendment added to the state constitution.

Jim Johnson was born on August 20, 1924, in Crossett (Ashley County) to T. W. Johnson and Myrtle Long Johnson, who owned a country grocery store. He had two brothers. In the 1920s, Crossett was a sawmill town, and Johnson’s family’s store competed with the mill’s company-owned store. Johnson served as class president and was also the first young man from Crossett to attend Arkansas Boys State in Little Rock (Pulaski County). In 1942, Johnson moved from Arkansas to Tennessee to attend law school at Cumberland University. In 1942, Johnson was drafted into the U.S. Marine Corps, serving in the Pacific Theater during World War II.

After serving in the marines and finishing law school, Johnson returned to Crossett in 1948. He married Virginia Lillian Morris on December 22, 1947; they had three sons. The couple opened a law business, with Virginia Johnson serving as Johnson’s legal secretary, as she did throughout his career.

Johnson became interested in politics after the 1948 Democratic National Convention, when many Southern delegates walked out of the convention and formed the States’ Rights Democratic Party (a.k.a. Dixiecrats). Johnson campaigned for the Dixiecrat presidential nominee, Strom Thurmond, in Arkansas in 1948. In 1950, Johnson, acting upon the advice of former Arkansas governor Ben Laney, ran for the Arkansas Senate and won.

After the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas U.S. Supreme Court decision, which declared school segregation unconstitutional, Johnson hatched plans to make segregation the main political issue in Arkansas. In 1955, he brought the White Citizens’ Council to Arkansas and started working to draft an amendment to the state constitution that would give Arkansas the right to interpose its will over that of the federal government. Johnson argued that the Supreme Court did not have the authority to create laws, and, therefore, the states could choose individually whether to enact the Court’s ruling about integration. Johnson’s ideas were not unique; other Southern states were already adopting the strategy of interposition.

In 1955, Johnson and the White Citizens’ Council of Arkansas (among others) protested the integration of the Hoxie School District. Johnson claimed that integration was a communist-inspired plot. This type of rhetoric was common during the 1950s among Southern segregationists, but it was Johnson who first brought this message to prominence in Arkansas. Segregationists and the Hoxie School Board took their fight to court. Although segregationist attempts to end the integration of Hoxie were unsuccessful, Johnson gained a following and garnered support for his proposed amendment.

Johnson ran for governor in 1956 against incumbent Orval Faubus. Largely due to Johnson’s popularity, Faubus was forced to face the issue of school segregation and came out against integration. Faubus won the 1956 election, but Johnson stayed active behind the scenes.

Despite Johnson’s loss, the electorate voted in favor of the amendment he had proposed, and it became Amendment 47 to Arkansas’s constitution. Amendment 47 gave Arkansas the right to ignore federal law when the population deemed it necessary, but it was deemed unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in Cooper v. Aaron in 1958. Johnson and segregationist forces in the state kept pressure on Faubus until Faubus decided to fight the desegregation of Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957. After this, Faubus became the segregationist face of Arkansas.

In 1958, Johnson was elected to the Arkansas Supreme Court. It was during his years as an associate justice that Johnson developed the persona and nickname “Justice Jim.” He served as an associate justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court for seven years and took pride in once being called a “color blind” judge by civil rights lawyer and activist Wiley Branton.

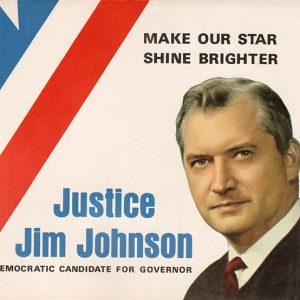

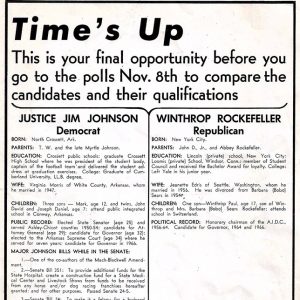

In 1966, he once again ran for governor, with the ideas he had espoused in 1956 campaign coming to the forefront, rather than his years of Arkansas Supreme Court service. This campaign helped solidify Johnson’s image as a racist, anti-communist troublemaker. Johnson won the Democratic primary in 1966, and his chances for winning were seen as strong, as there had not been a Republican governor in Arkansas since the Reconstruction era. As the election grew closer, however, Republican candidate Winthrop Rockefeller became increasingly popular across the state. Rockefeller had worked closely with Orval Faubus before 1957 and had brought jobs and infrastructure to the state.

In 1966, Johnson lost the election to Rockefeller, ending the reign of post-Reconstruction Democratic governors. In 1968, Johnson ran for a U.S. Senate seat, challenging longtime U.S. senator J. William Fulbright. Although Johnson believed he had ample support to beat the popular senator, he failed to capture the voters the way he had in 1966. In this same election, Virginia Johnson ran for governor, the first woman to do so in Arkansas. Both Johnsons lost their races, although Virginia Johnson did achieve some popularity as a conservative female candidate, forcing Marion Crank into a runoff election in the primary, although Rockefeller again won election. Johnson then managed the Arkansas campaign for presidential candidate George Wallace of the American Independent Party.

By 1970, Johnson’s political career was over. He returned to his law practice, now located in Conway (Faulkner County) and continued to comment on politicians and political activities, making enemies out of some of Arkansas’s governors, most notably Bill Clinton. In 1980, he became a Republican and was the Republican nominee for chief justice of the Arkansas Supreme Court in 1984.

Johnson, who had been suffering from cancer, took his own life at his home at Beaverfork Lake near Conway on February 13, 2010.

For additional information:

Jacoway, Elizabeth. Turn Away Thy Son: Little Rock, The Crisis That Shocked the Nation. New York: Free Press, 2007.

Jim Johnson Papers. Arkansas State Archives, Little Rock, Arkansas.

McMillen, Neil R. “The White Citizens Council and Resistance to School Desegregation in Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 66 (Summer 2007): 125–144.

Reed, Roy. Faubus: The Life and Times of an American Prodigal. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Simmons, Bill. “Segregationist ‘Justice Jim’ Dies.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, February 15, 2010, pp. 1B, 6B.

Totten, Marie Cathryn. “‘A Rabble Rouser All the Time’: Jim Johnson and the Politics of Massive Resistance in Arkansas.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2021. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/4139/ (accessed July 7, 2022).

Williams, Marie. “The Road to the Central High Crisis: Jim Johnson’s Manipulation of the Southern Red Scare in Arkansas and the Integration of Hoxie.” MA thesis, Arkansas Tech University, 2014.

Marie Williams

Arkansas Tech University

Amendment 44

Amendment 44 World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Johnson Campaign

Johnson Campaign  Johnson vs. Rockefeller

Johnson vs. Rockefeller  Johnson Campaign Tab

Johnson Campaign Tab  Virginia and Jim Johnson

Virginia and Jim Johnson

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.