calsfoundation@cals.org

Little Rock School Desegregation Cases (1982–2014)

aka: Little Rock School District, et al v. Pulaski County Special School District et al.

From 1982 until 2014, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas, Western Division, handled Little Rock School District, et al. v. Pulaski County Special School District et al. At least six federal district judges presided over the case during this span of time. In 1984, the district court ruled that three school districts situated in Pulaski County were unconstitutionally segregated: the Little Rock School District (LRSD), the Pulaski County Special School District (PCSSD), and the North Little Rock School District (NLRSD). One reason for the ruling was that the population of Little Rock was approximately sixty-five percent white in 1984, while seventy percent of Little Rock School District students were Black. Those who brought the case feared that white students were leaving LRSD to go to the two other school districts in the county: NLRSD and PCSSD. The court placed all three districts under court supervision until they could be declared unitary—meaning they met the criteria of desegregation laid out by the U.S. Supreme Court in Green v. County School Board of New Kent County (1968). The criteria included an acceptable ratio of Black to white students and faculty, as well as absolute equality in facilities and extracurricular activities. Over the course of the litigation, several intervenors—those who intervene as a third party in a legal proceeding—also entered the proceedings on behalf of African-American students in the county.

While this particular case began in 1982, its origins stretched back to the 1950s, when President Dwight Eisenhower sent federal troops to protect nine Black students who were trying to attend Central High School in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in September 1957. As a response, Governor Orval Faubus closed all public schools in Little Rock at the end of the school year and won a 1958 referendum against integration, whereby the voters of Little Rock chose to keep their public schools closed for the 1958–59 school year (which became known as the Lost Year) rather than allow integration. However, in May 1959, local school board elections saw a more moderate group come to power—people who supported some token integration. However, concerns could still be heard regarding the unequal treatment afforded Black students in Pulaski County.

From 1966 to 1971, the Little Rock School District dealt with challenges to its integration policies in a court case brought by Delores Clark, an African-American mother who objected to her children being denied entrance to predominately white elementary and junior high schools. An important turning point in this case came in 1971, when the U.S. District Court mandated busing in order to better integrate area schools. In response, white families increasingly left LRSD. A recurring problem since the Clark case has been so-called white flight away from Little Rock and toward bedroom communities completely outside of Little Rock and Pulaski County.

In response to continued racial disparities in education, in November 1982, LRSD filed an action against PCSSD, NLRSD, the State of Arkansas, and the State Board of Education seeking, among other things, one consolidated and integrated countywide school district. On April 13, 1983, the district court dismissed the claim against the State of Arkansas but refused to take similar action concerning the State Board of Education. The court held that the Board of Education possessed a direct supervisory relationship over all the school districts and, therefore, could be held liable for causing increased segregation in Little Rock. The district court concluded that the dismissal of the State of Arkansas had no practical effect on the disposition of the lawsuit. The district court separated the liability and remedy phases of the litigation and held liability hearings from January 3 to January 13, 1984.

On April 13, 1984, the district court issued its decision on liability, finding that PCSSD and NLRSD had failed to establish unitary, integrated school districts and had committed unconstitutional and racially discriminatory acts that resulted in substantial segregation. The court concluded that NLRSD and PCSSD had taken actions that led to segregation in each of the school districts in the county, and that the districts had failed to redress the situation. The district court also reiterated that the State Board of Education was a party to the discriminatory actions of the school districts in question. The district court concluded that the only solution to these inter-district violations was consolidation, and Judge Henry Woods scheduled hearings to consider the consolidation of the three school districts into one.

The first remedial hearings took place from April 30 through May 5, 1984. Before these hearings were held, a group of Black parents in Little Rock—the Joshua intervenors—sought unsuccessfully to bring separate concerns to the proceedings. The intervenors’ concerns included direct financial compensation to majority Black districts. On May 23, 1984, the appeals court ordered the district court to hear the Joshua intervenors’ evidence concerning other alternatives to consolidation. Meanwhile, the defendant school districts had also appealed the order for the consolidation of the three school districts. On May 23, 1984, the appeal was dismissed as premature, but the appeals court could reopen the proceedings to permit PCSSD and NLRSD to advance other alternatives to consolidation.

The district court held further remedial hearings from July 30 through August 2, 1984, and heard evidence on alternative plans submitted by PCSSD, NLRSD, and the Joshua intervenors. On November 19, 1984, the district court ruled that consolidation of the three school districts was necessary to end the constitutional violations. The court also reaffirmed that the State Board of Education needed to take further action to desegregate the schools in question. The district court subsequently denied motions by the defendants for reconsideration.

In November 1985, the Eighth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the consolidation of all three districts into one, calling the remedy too extreme for the violation. The court also ordered most Little Rock School District boundary lines to coincide with the city limits. As a result, PCSSD lost almost 8,000 students, and fourteen schools moved from PCSSD to LRSD. LRSD therefore gained thirty-eight square miles, fourteen schools, and 7,000 students. The ratio of Black to white students went from 70–30 percent to 60–40 percent.

In March 1989, attorneys for the state, the three Pulaski County school districts, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the intervenors signed a proposed financial settlement in which the state would pay about $129.75 million over ten years to the three districts for the support of remedies such as magnet schools and busing. The Arkansas General Assembly subsequently agreed to pay the amount. In July 1990, Judge Henry Woods (who had made the 1984 decision) issued an order recusing himself from the school desegregation case, and U.S. District Judge Susan Webber Wright, now the chief judge, took Woods’s place in the case.

In 1998, LRSD and John Walker, an attorney representing Black students, agreed on a new desegregation and education plan to replace the outmoded one from 1989. In an admission that more needed to be done to advance desegregation in Little Rock, this three-year plan mandated two new elementary schools, two new middle schools, reduced busing of Black students out of their neighborhoods, and relaxed racial-balance guidelines; it also mandated employment of desegregation experts. The plan increased funding for college scholarships for students in virtually all-Black elementary schools and encouraged an emphasis on reading and math instruction. The plan was approved by Judge Wright, meaning LRSD would have been released from federal court monitoring by 2001—even though this did not come about.

By early 2002, Wright objected to requests made by LRSD that court monitoring end, and her successor, Bill Wilson Jr., believed that LRSD needed to be monitored in order to ensure improvement in the academic achievement of Black students. This decision was affirmed by the Eighth District U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Two more requests were made by LRSD, in 2004 and 2006, to be released from federal supervision, and both were rejected by the district court on the grounds that LRSD had not successfully assessed and evaluated its academic programs. Finally, in 2007, Judge Wilson declared LRSD unitary, and that decision was upheld by the Eighth District U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in 2009. PCSSD and NLRSD sought to be declared unitary in 2007, and Judge Miller held hearings on this issue in 2010.

On May 19, 2011, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas found that NLRSD was unitary in all but one area, but that PCSSD had not satisfied requirements for unitary status in nine of twelve areas. At the same time, the court released the state from most—though not all—of its desegregation funding obligations. The federal district court continued its jurisdiction over the 1989 settlement agreement and the three school districts until all districts were declared completely unitary. In 2014, both Little Rock and North Little Rock School Districts were ruled unitary, or desegregated. However, PCSSD still has not yet been ruled unitary by the federal district court and remains under federal monitoring to remedy academic underperformance and student discipline problems, as well as facility maintenance issues.

In January 2014, federal judge Price Marshall gave final approval to a settlement that would allow the state to phase out payments of millions of dollars to LRSD, NLRSD, and PCSSD that had encouraged various desegregation programs such as new integrated magnet schools offering specialized academic programs, as well as transportation for students to areas where they are in the racial minority. By this time, John Walker, who represented Black students and parents in the suit and had begun serving in the Arkansas General Assembly, conceded that the money had not changed the realities in the district, including the performance gap between white and Black students—even as many seek to keep the issue before the public. The 2014 settlement ruled that the State of Arkansas would continue to pay out $65.8 million a year until 2018. These payments would be earmarked for facilities projects, as well as continued desegregation efforts, such as aid with student transportation. In 2015, the State Board of Education voted to remove the Little Rock School Board and take over the district, citing continued controversy over the quality of student education.

When looking back over the past sixty years of desegregation efforts in Little Rock, historians note both successes and failures. In terms of success, there has been one African-American school superintendent for LRSD, in addition to several Black school board members, thus signaling a greater ability for African Americans to have a say in the education of Little Rock’s children. This can be seen in the continued academic success of schools such as Central High School, now an integrated institution. However, most observers note that LRSD has been re-segregating over the last few decades, largely due to white flight—as well as to white attendance at private schools—so that the number of white students in Little Rock not enrolling in the city’s public schools is approaching fifty percent. In 2015, the student population of LRSD was less than nineteen percent white.

For additional information:

Branton, Wiley A. “Little Rock Revisited: Desegregation to Resegregation.” Journal of Negro Education 52, no. 3 (Summer 1983): 250–269.

Elliott, Debbie. “Decades Later, Desegregation Still on the Docket in Little Rock.” National Public Radio, January 13, 2014. http://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/01/07/260461489/decades-later-desegregation-still-on-the-docket-in-little-rock (accessed October 14, 2020).

Little Rock School District v. Pulaski County Special School District No 1, 778 F. 2d 404. http://openjurist.org/778/f2d/404/little-rock-school-district-v-pulaski-county-special-school-district-no-1 (accessed October 14, 2020).

Stinson Leonard Street LLP. “Settlement Agreement Could Conclude Little Rock Desegregation Cases.” Lexology, January 29, 2014. http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=75bc5af2-d522-48aa-950f-13c0f02f3f03 (accessed October 14, 2020).

Taylor, Theman, Sr. “Cracks in ‘the Rock’: A Disturbing Aftermath—The Declining Significance of Desegregation—‘Separate but Equal’ Revisited.” Arkansas State Press, March 14, 1996, pp. 1, 6.

Trimble, Mike. ”The School Board Blues.” Arkansas Times, December 1987, pp. 40–43, 56, 58–61.

Vinzant, David Gene. “Little Rock’s Long Crisis: Schools and Race in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1863–2009.” PhD diss., University of Arkansas, 2010.

Woods, Henry, and Beth Deere. “Reflections on the Little Rock School Case.” Arkansas Law Review 44, no. 4 (1991): 972–1006.

Ryan Jordan

National University

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century)

Civil Rights Movement (Twentieth Century) Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Law

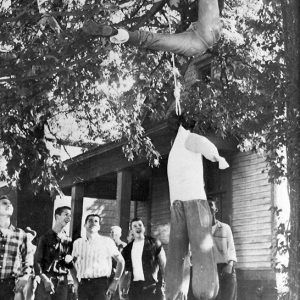

Law Effigy Hanging

Effigy Hanging

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.