calsfoundation@cals.org

Ozark Mountain Folk Fair

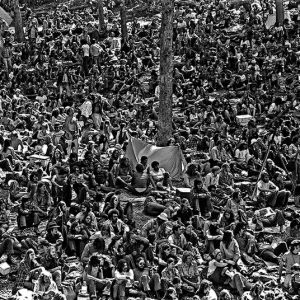

The Ozark Mountain Folk Fair was a music festival and craft fair held north of Eureka Springs (Carroll County) in 1973 on Memorial Day weekend (May 26–28). The festival drew an audience from around the United States, with an estimated attendance of up to 30,000, and featured a diverse mix of rock, blues, bluegrass, gospel, country, and folk music performances.

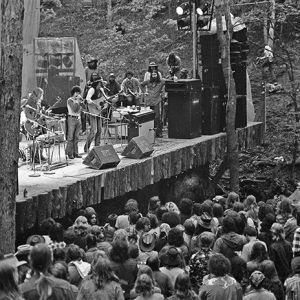

The rise of 1960s and early 1970s counterculture throughout America was especially relevant within the environmental back-to-the-land movement burgeoning in the Arkansas Ozarks, in which people sought a more mindful and sustainable way of life and rejected commercial aspects of society. In this culture, journalist Edd Jeffords, founder of the Ozark Mountain Folklore Association, organized the Ozark Mountain Folk Fair. The setting for the festival was ten miles north of Eureka Springs off Highway 23 on 120 acres of wooded hills christened the Oak Hill EcoPark. The land was partially cleared to create a natural, 108,000-square-foot amphitheater designed by architect Albert Skiles and built to accommodate 40,000 spectators.

The Ozark Folk Fair included areas for natural foods concessions, the Crafts Village space for more than sixty artists and craft vendors, and a section of land for camping and access to water, in addition to the main amphitheater. Tickets cost twelve dollars in advance for the weekend or five dollars per day. A first-aid tent was constructed and staffed by physicians who, aside from one case of snake bite, mostly treated cuts, bruises, and drug overdoses.

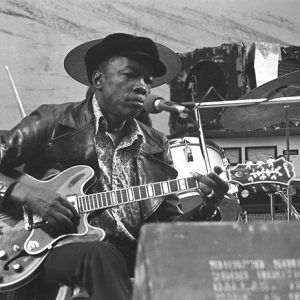

The festival featured music from Earl Scruggs, John Lee Hooker, Big Mama Thornton, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Leo Kottke, Mason Proffit, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and Stone County native Jimmy Driftwood, among many others. Two daily music shows were scheduled from noon to 5:00 p.m. and from 7:00 p.m. to midnight. Documentary filmmaker Les Blank attended to record a film, and a team of photographers was organized to document the festival.

Concurrent with (and in some conflict with) the countercultural movement within Eureka Springs was the resurgence in popularity of Christian-based tourism driven largely by the Five Sacred Projects (including the Great Passion Play and the Christ of the Ozarks statue) undertaken in the city by Gerald L. K. Smith. Proselytizers from a local street ministry attended the festival to pass out copies of the New Testament, and John Michael Talbot, guitarist for Mason Proffit, is said to have been moved by what he saw during the festival to quit the band and purchase land nearby for his Little Portion Hermitage in Berryville (Carroll County).

Although the three days were plagued by heavy rainfall and resulting muddy conditions, the festival was considered by many to be a great cultural success. Despite plans to make the Folk Fair an annual event, it was a unique occurrence; pressure from local business owners, religious leaders, and law enforcement agencies was said to have contributed to the singularity of the event. These groups opposed the lifestyle and drug culture associated with most of the festivalgoers drawn to the area, and they feared that another festival would drive other tourists away. The Ozark Folk Fair can be viewed, however, as a marker for the beginning of the liberal cultural influence of environmentalists, musicians, and artists that, in part, characterizes Eureka Springs in the twenty-first century.

For additional information:

Griffith, April. “Ozark Mountain Folk Fair: History in Our Backyard.” The Back-Stay: A Blog from the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History. https://shilohmuseum.org/author/agriffith/ (accessed September 28, 2021).

Mathis, Jim. Ozark Mountain Folk Festival: May 1973. Overland Park, KS: MathisPhoto, 2009.

“Ozark Mountain Folkfair Begins May 26.” Northwest Arkansas Times, May 18, 1973, p. 10.

Pryor, Tim. “Area Residents Attend Folk Fair.” Lawrence Daily Journal, May 29, 1973, p. 3.

Stockslager, Mary. “Despite Rain, Other Problems, Ozark Folkfair Finishes Stand.” Springdale News, May 28, 1973, p.8.

———. “Folkfair Work Goes on, Despite Rain.” Springdale News, May 25, 1973, p.11.

April Griffith

Shiloh Museum of Ozark History

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022

Divergent Prosperity and the Arc of Reform, 1968–2022 Ozark Institute [Organization]

Ozark Institute [Organization] Recreation and Sports

Recreation and Sports John Lee Hooker

John Lee Hooker  Mason Proffit

Mason Proffit  Ozark Mountain Folk Fair Audience

Ozark Mountain Folk Fair Audience  Ozark Mountain Folk Fair

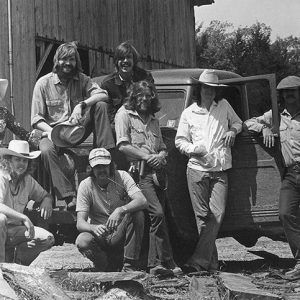

Ozark Mountain Folk Fair  Ozark Mountain Folk Fair Staff

Ozark Mountain Folk Fair Staff

One day, this dude that I had just met asked if I wanted to go to the Ozark Folk Festival. Of course I agreed to go! We put up a tent but only had one sleeping bag. Imagine that 😘. Rained all night and for three days, but we had food, smoked, and rocked to the best music ever. By the way, I married that guy. We had forty-one years together. My soulmate, James, passed away but we knew those days in Arkansas were the beginning of a beautiful life together.

My buddy and I were traveling across country from Oregon when we found out about it. I remember it being pretty wet, and there were tornadoes in the area, but we had a good time and good memories.

I attended the festival with several friends. We all had the time of our lives. The lineup was outstanding. I still have two posters that were made to publicize the event. I’m not sure if anyone else has them.

I read your history of the 1973 Folk Fair with great interest. I was one of the organizers and the on-stage emcee for the event. Although we did have opposition from the local politicians, I believe the main reason there was never another one was the financial loss. It was indeed a cultural success, but it took Edd Jeffords many years to pay off the debts.

Thank you for hosting this information! My dad went to this festival. I’m thirty-five and apparently finally old enough for him to tell me about these sorts of things. I wasn’t sure I’d be able to find more information about it but love that I did.