calsfoundation@cals.org

Fulton County

| Region: | Northeast |

| County Seat: | Salem |

| Established: | December 21, 1842 |

| Parent County: | Izard |

| Population: | 12,075 (2020 Census) |

| Area: | 618.04 square miles (2020 Census) |

| Historical Population as per the U.S. Census: | |||||||||

|

1810 |

1820 |

1830 |

1840 |

1850 |

1860 |

1870 |

1880 |

1890 |

1900 |

|

– |

– |

– |

– |

1,819 |

4,024 |

4,843 |

6,720 |

10,984 |

12,917 |

|

1910 |

1920 |

1930 |

1940 |

1950 |

1960 |

1970 |

1980 |

1990 |

2000 |

|

12,193 |

11,182 |

10,834 |

10,253 |

9,187 |

6,657 |

7,699 |

9,975 |

10,037 |

11,642 |

|

2010 |

2020 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

12,245 |

12,075 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Population Characteristics as per the 2020 U.S. Census: | ||

| White |

11,249 |

93.2% |

| African American |

27 |

0.2% |

| American Indian |

66 |

0.5% |

| Asian |

35 |

0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

0 |

0.0% |

| Some Other Race |

63 |

0.5% |

| Two or More Races |

635 |

5.3% |

| Hispanic Origin (may be of any race) |

154 |

1.3% |

| Population Density |

19.5 people per square mile |

|

| Median Household Income (2019) |

$35,405 |

|

| Per Capita Income (2015–2019) |

$19,697 |

|

| Percent of Population below Poverty Line (2019) |

20.7% |

|

Fulton County, located in the Ozark Foothills of north-central Arkansas, borders the Missouri state line on the north, Sharp County to the east, Izard County to the south, and Baxter County to the west. The population in the 2020 census was over 12,075, while the county seat, Salem, claimed 1,566 residents. The rolling, forested hills of Fulton County are well suited for pasture, moderately suited for woodland use, and poorly suited for cultivated crops. Past residents of Fulton County turned to the timber and livestock industries as substantial sources of income. Fulton County has four incorporated cities: Mammoth Spring, Salem, Cherokee Village, and Viola. Fulton County is home to Spring River, a popular canoeing site, and the famous baseball player Preacher Roe.

Pre-European Exploration

Before the arrival of Europeans, Native American groups such as the Osage hunted in the area now known as Fulton County. No evidence of any large-scale settlements exists, although fragments of arrowheads, spear points, and other remains of temporary camps have been found along the creek banks and river bluffs.

European Exploration and Settlement

The first white man to visit Arkansas was Hernando de Soto in 1541, who came as far north as the White River but not to the Fulton County area. Later notable visitors to Arkansas—Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet in 1673, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle in 1682, and Henri de Tonti in 1686—also ignored the uplands of the Ozarks. Like the Osage and other Native American groups, white explorers and hunters may have briefly passed through the area but never settled there permanently.

Louisiana Purchase through Early Statehood

The first legally recognized white resident of Fulton County, William P. Morris, used his land grant to acquire 160 acres in the present Salem area in the 1830s. Fulton County was created on December 21, 1842, by the state legislature, carving out part of Izard County and present-day Baxter County. William P. Morris officially donated the land to be used as a county seat on July 4, 1844. The town became known as Pilot Hill because of the large hill overlooking the flat land between the South Fork River and the local creek. According to Goodspeed’s Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northeast Arkansas, the first courthouse was a one-room log cabin. It was replaced with a larger log structure containing a courtroom and clerk’s office. Slaves were brought to antebellum Fulton County; there were eighty-eight counted in the 1860 census along with 3,936 white citizens. Although few enslaved people were held in bondage in Fulton County, S. W. Cochran, the owner of at least nine slaves, represented the county at the 1861 Secession Convention.

Civil War through Reconstruction

The American Civil War made a huge impact on Fulton County. Settlers who lived in the rocky uplands of the county did not own slaves, but the settlers living along the fertile valleys of the rivers and creeks did. On May 27, 1861, citizens at Pilot Hill organized a company of 108 home guards to protect the local people. However, residents joined both Confederate and Union forces. One early settler who served in the Confederate army was Ephraim Sharp, who lived most of his adult life in the county.

On March 12, 1862, the realities of war were brought home as Union cavalry forces crossed the Missouri state line and established themselves at Spring River Mill (now Mammoth Spring) after engaging a squad of Confederates. The next day, March 13, they continued on toward Salem and fought with Confederates at a place northeast of Pilot Hill near the South Fork of the Spring River in what is known as the Action at Spring River. The Union cavalry succeeded in dividing and disorganizing local Confederate cavalry patrols before retreating into Missouri. The Federal Army of the Southwest under the command of Major General Samuel Ryan Curtis entered Arkansas from Missouri near Salem on April 29, 1862, after his victory at the Battle of Pea Ridge. The crossing into Arkansas at Fulton County was part of the larger Pea Ridge Campaign, and the army would eventually capture Helena (Phillips County), which would remain a Union stronghold for the remainder of the war.

Troops on both sides subsequently left the area, and Fulton County residents lived in a guerrilla warfare state for the next three years. Bands of thieves known as “bushwhackers” and “jayhawkers” roamed the area, raiding local farms, and terrorizing the citizens; they also burned the county courthouse, destroying land and census records. A wagon train of Unionist citizens fleeing the state was attacked near Fulton in May 1864 by guerrillas, leading to the death of at least eighty men and an unknown number of women and children. Numerous other scouting expeditions passed through the county due to its proximity to the Missouri state line, including in January 1864, February 1864, and March 1864.

In 1868, former Confederate veterans met at Bennett’s Bayou (now in Baxter County) in the western part of the county and formed a local Ku Klux Klan (KKK), which was responsible for the murder of Freedmen’s Bureau agent Simpson Mason. When Governor Powell Clayton declared martial law for certain counties in the state, he also sent troops to the seat of Fulton County, confusingly known at this time as both Pilot Hill and Salem, to put down the revolt. Such destruction prompted returning veterans on both sides to rebuild peaceful communities. On February 20, 1872, the county seat and its post office officially changed its name to Salem, which in Hebrew means “city of peace.”

Post Reconstruction through Early Twentieth Century

From the ashes of war, Fulton County began to grow again and to develop small towns and communities. Some of these communities still exist as a local church, post office branch, or convenience store; others simply faded away. These unincorporated communities include Agnos, Bexar, Byron, (Indian) Camp, Draft, Elizabeth, Fairview, Flint Springs, Frenchtown, Fryatt, Gepp, Glencoe, Heart, Kittle, Many Islands, Mitchell, Moko, Morriston, Mount Calm, Ott, Pickren Hall, Ruth, Pilot, Saddle (a.k.a. Sharp’s Mill, South Fork), Shady Grove, State Line, Sturkie, Union, Vidette, Wheeling, and Wild Cherry.

Each community had its own general store, two or three churches, a school, and a cemetery. Salem, as county seat, had established a bank, mortuary, and several law offices and doctor’s offices in the early 1900s. Mammoth Spring, due to its location at the head of the Spring River, attracted a railroad line in the early 1880s and, in about 1887, created an electric power dam on the river. However, the economy remained largely agrarian, with many small farms scattered across the countryside. Farmers grew cotton and corn as cash crops, raised hogs and cattle for market and personal consumption, and relied heavily upon gardens to supplement their diet.

When the Great Depression hit in 1930, many struggling farmers lost their farms. Yet the Rural Electrification Act (REA), a New Deal program, allowed local residents to form an electric cooperative, North Arkansas Electric Cooperative (NAEC), in 1939. This organization not only provided electricity but also much-needed jobs to the county. NAEC would eventually service most of Fulton County and become a business leader in Sharp, Izard, and Baxter counties as well.

World War II through Modern Era

Industrialization in other parts of the United States attracted Fulton County youth to leave home in search of economic opportunities. Despite the arrival of the Tri-County Shirt Factory plants in the 1960s, the county population reached an all-time low in the mid-twentieth century. Desegregation was not an issue in Fulton County—in the 1950s and 1960s, there were fewer than five African Americans living there, all of them above the age of twenty-one. Fulton County native Arthur Brann Caldwell led the Civil Rights Section of the Department of Justice from 1952 to 1957, including during the Central High Crisis.

Several former county residents went on to become well known nationally. “Preacher” Roe, whose family settled in Wild Cherry when he was three and who attended school in Viola, played for the St. Louis Cardinals in 1938, the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1944 to 1947, and the Brooklyn Dodgers from 1948 to 1954, with Jackie Robinson, the first African-American player in the major leagues. Later, Roe gave back to his home county by developing a baseball park, Preacher Roe Park, in Salem, where he pitched an exhibition game every fall for the first eight years. Actress Tess Harper spent her childhood in Mammoth Spring and graduated from high school there in 1968. She starred in films such as Crimes of the Heart, for which she received an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actress, and Tender Mercies with Robert Duvall. James Robinson Riser, held as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam for more than seven years, received the Air Force Distinguished Service Medal and the POW Medal for actions he undertook while held in captivity.

Tourism became part of the Fulton County economy in the twentieth century, but only in the Spring River region around Mammoth Spring. The only railroad in the county, built in 1883, traveled alongside the Spring River as the major thoroughfare between Springfield, Missouri, and Memphis, Tennessee. At the turn of the century, residents of Memphis often traveled to Mammoth Spring to spend the summer. Now, tourists come to visit Mammoth Spring State Park, to float and fish the Spring River, and to explore the historic attractions of downtown Mammoth Spring.

Fulton County remains a small, rural area in the Ozark Foothills. Today, many of the residents are retirees who have returned to their childhood home. Other retirees are attracted by the scenic beauty and reasonable rate of living. Such changes reflect both the adapting economy and the natural beauty of the area.

For additional information:

Blevins, Brooks. “Reconstruction in the Ozarks: Simpson Mason, William Monks, and the War That Refused to End.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 77 (Autumn 2018): 175–207.

Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northeast Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Company, 1889.

Fulton County, Arkansas: History and Families. Morley, MO: Acclaim Press, 2008.

Fulton County Chronicles. Salem, AR: Fulton County Historical Society (1983–).

Hunt, Grace Cunningham, Mrs. G. T. Cunningham, J. Orville Benton, and Jo Ray. “Then and Now in Fulton County, Arkansas.” Fulton County Chronicles 1 (Winter 1982): 7–13.

“Murder in Fulton County, Part One.” Baxter County History 23 (January/March 1997): 9–11.

“Murder in Fulton County, Part Two.” Baxter County History 23 (June 1997): 34–38.

Roe, Preacher, and Sarah Preslar. When Baseball Was Still a Game: Truth, Legends, Tales, and Photos from Preacher Roe. Hardy, AR: Catalyst Apex Publishing, 2005.

Soil Survey of Fulton and Izard Counties, Arkansas. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service, 1984.

Varno, Susan, and Dan Tyree. “One Dead as Result of Stabbing Affray.” Izard County Historian 30 (January 2005): 14–18.

Sarah E. Simers

Salem, Arkansas

Revised 2022, David Sesser, Henderson State University

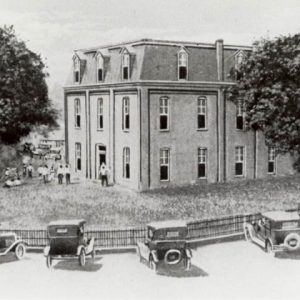

Fulton County Courthouse

Fulton County Courthouse  Fulton County Courthouse

Fulton County Courthouse  Fulton County Courthouse

Fulton County Courthouse  Fulton County Map

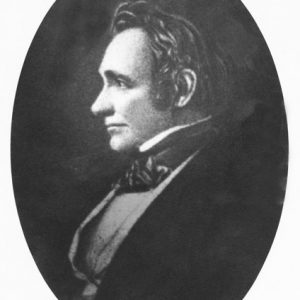

Fulton County Map  William Fulton

William Fulton  Mammoth Spring State Park

Mammoth Spring State Park  Mammoth Spring

Mammoth Spring  Mammoth Spring State Park

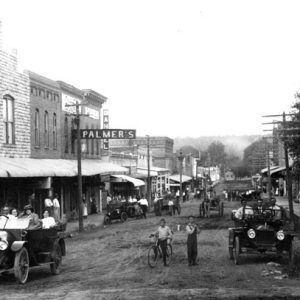

Mammoth Spring State Park  Mammoth Spring Street Scene

Mammoth Spring Street Scene  Mammoth Spring Street Scene

Mammoth Spring Street Scene  Mammoth Spring Train Depot

Mammoth Spring Train Depot  Nettleton Hotel

Nettleton Hotel  Salem Tornado, 1947

Salem Tornado, 1947

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.