calsfoundation@cals.org

Arkansas State Press

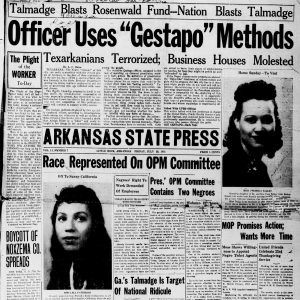

The weekly Arkansas State Press newspaper was founded in Little Rock (Pulaski County) in 1941 by civil rights pioneers Lucious Christopher Bates and Daisy Gatson Bates. Modeled on the Chicago Defender and other Northern, African American publications of the era—such as The Crisis, a magazine of the National Association of Colored People (NAACP)—the State Press was primarily concerned with advocacy journalism. Articles and editorials about civil rights often ran on the front page. Throughout its existence, the State Press was the largest statewide African American newspaper in Arkansas. More significantly, its militant stance in favor of civil rights was unique among publications produced in Arkansas.

Although in later years, Daisy Bates would be recognized as co-publisher of the paper and, in fact, devoted many hours each week to its production under her husband’s supervision, it was L. C. Bates who was responsible for its content and the day-to-day operation of the paper.

The State Press ran stories that spotlighted the achievements of Black Arkansans as well as social, religious, and sporting news. The eight-page paper was published on Thursdays, carrying a Friday dateline. Pictures, many of them taken by staff photographer Earl Davy, were in abundance throughout the paper. Invariably, a tasteful photograph of a Black woman who had recently been given some honor or award ran on the front page. It would be not until after the civil rights movement in the 1960s that newspapers owned by whites would begin to show African Americans in a positive light. In addition to the central Arkansas area, the State Press was distributed in towns that had sizable Black populations, including Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), Texarkana (Miller County), Hot Springs (Garland County), Helena (Phillips County), Forrest City (St. Francis County), and Jonesboro (Craighead County). The newspaper’s coverage included social news from surrounding areas of the state, and the State Press routinely reported incidents of racial discrimination. “Negro Soldiers Given Lesson in White Supremacy in Sheridan,” the headlines of the State Press read on July 17, 1953, with a story that concerned African American soldiers passing through Arkansas from elsewhere, who were not accustomed to deferring to whites in the South and sometimes ignored or were not familiar with laws and customs requiring racial segregation.

For most of the paper’s life, the offices were on West 9th Street in the heart of the Black community in Little Rock. Its coverage of the death of a Black soldier at the hands of a white soldier on 9th Street in March 1942 made the paper required reading for most African Americans, as well as many white people. The coverage of this single incident boosted circulation but more importantly identified the State Press as the best source of news about African Americans and their fight for social justice. Temporarily boycotted by many white advertisers because of its tabloid style commitment to civil rights, the State Press survived by increasing circulation to 20,000. Throughout its existence, the State Press supported politicians and policies that challenged the status quo for African Americans within the state and nation. Besides endorsing and promoting the leadership of Pine Bluff activist W. Harold Flowers in the 1940s, the State Press supported the candidacy of left-leaning Henry Wallace for president in 1948.

Always a backer of the leadership of the national policies of the NAACP, the State Press became a militant supporter of racial integration of the public schools during the 1950s, an editorial stance which put it at odds not only with white people in Arkansas but also many African Americans as well. On May 21, 1954, four days after the momentous decision in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, which declared an end to racial segregation in public schools, the State Press editorialized, “We feel that the proper approach would be for the leaders among the Negro race—not clabber mouths, Uncle Toms, or grinning appeasers to get together and counsel with the school heads.” The State Press took on both those in the Black and white communities who felt either the time was not yet ripe for school integration or, in fact, would never be. For the next five years, until its demise in 1959, the State Press was the sole newspaper in Arkansas to demand an immediate end to segregated schools. In issue after issue, it advocated the position of the NAACP, which led the fight nationally and in Arkansas to enforce the promises of the Brown decision. During the tumultuous fall of 1957, when Governor Orval Faubus and his supporters resisted even token desegregation of Central High School in Little Rock, and federal troops were brought in to guarantee the right of nine African American students to attend Central High School, the State Press fought a continuing battle on their behalf. On November 29, 1957, the State Press explained in a front-page editorial, “The Negro is angry, because the confidence that he once had in Little Rock in keeping law and order, is questionable as the 101st paratroopers leave the city.” On December 13, this editorial appeared on the front page: “It is the belief of this paper that since the Negro’s loyalty to America has forced him to shed blood on foreign battle fields against enemies, to safeguard constitutional rights, he is in no mood to sacrifice these rights for peace and harmony at home.”

Its unwavering stance during the Little Rock desegregation crisis in 1957 resulted in another boycott by white advertisers. Despite direct financial support by the national office of the NAACP and support of the paper by the placement of advertisements by NAACP organizations and other groups and individuals throughout the country, this boycott, as well as intimidation of Black news carriers, proved fatal. The last issue was published on October 29, 1959.

Daisy Bates’s attempt to revive the State Press in 1984 after the death of her husband was financially unsuccessful, and she sold her interest in the paper in 1988 to Darryl Lunon and Janis Kearney, who continued to publish it until 1997.

For additional information:

Arkansas State Press. Chronicling America, Library of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84025840/ (accessed July 11, 2023).

Bates, Daisy. The Long Shadow of Little Rock. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1987.

Grant, Rachel. “‘Do It Now or Forget It”: Daisy Bates Resurrects the Arkansas State Press, 1984–1988.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 2010.

Kirk, John A. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940–1970. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

Smith, C. Calvin. “‘From Separate But Equal to Desegregation’: The Changing Philosophy of L.C. Bates.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 42 (Autumn 1983): 254–270.

Stockley, Grif. Daisy Bates: Civil Rights Crusader from Arkansas. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2005.

Wassell, Irene. “L. C. Bates, Editor of the Arkansas State Press.” MA thesis, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, 1983.

Grif Stockley

Butler Center for Arkansas Studies

Arkansas State Press

Arkansas State Press  Arkansas State Press Cover

Arkansas State Press Cover  Daisy Bates

Daisy Bates  L. C. Bates

L. C. Bates  Geleve Grice

Geleve Grice

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.