calsfoundation@cals.org

Quapaw

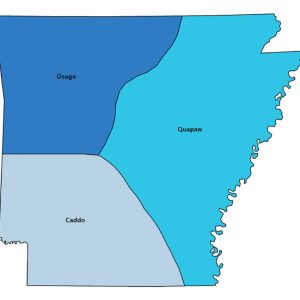

The Quapaw are members of the Dhegiha Siouan language group, which also includes the Osage, the Omaha, the Ponca, and the Kansa. They first appeared in historical accounts in 1673 when they encountered the first French explorers in the Mississippi River Valley, led by Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Joliet. The French called the Quapaw the “Arkansas,” the Illini word for “People of the South Wind” and so named the river and the countryside after them. At that time, the Quapaw lived in four villages along the Mississippi River. They established one village, Kappa, on the east bank of the Mississippi. Two others, Tongigua and Tourima, were located on the west bank and a fourth, Osotouy, at the mouth of the Arkansas River. The last three were most likely located in present-day Desha County.

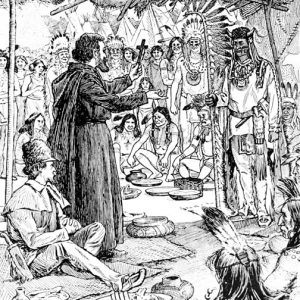

The tribe was divided into two large moieties (divisions)—Earth and Sky—and into twenty-one clans. Each moiety and all clans had members in all four villages, so that each individual had close ties to people in every community. The two moieties shared responsibility for the calumet, the sacred pipe that connected the people to Wakondah, the powerful, sacred force that blessed all things with life. The calumet was also shared with strangers and visitors. Smoking the calumet and the accompanying rituals converted strangers into kin with reciprocal obligations. French explorers were some of the first to witness and participate in the calumet rituals. Individuals and clans also had their guardian spirit beings.

Villages included longhouses occupied by several families surrounding the central plaza. A council house for the meetings of the village chief and elders was closest to the plaza. Nearby, a covered and partially enclosed platform—the French called it an antichon—was located for the greeting of visitors and strangers. Each village was laid out so that Sky clans were on the opposite side of the sacred circle from the Earth clans. In marriage, the Quapaw, unlike many southern tribes, were patrilineal, tracing descent through the father’s family, and patrilocal, meaning that wives lived with their husbands’ families. A Quapaw of one moiety could not marry a person from the same moiety.

There is lively scholarly debate about the origins of the Quapaw and their presence in Arkansas. Some archaeological evidence suggests that the Quapaw are descended from the people of Pacaha and possibly the people of Casqui as well. Both of these groups lived in Arkansas in the sixteenth century. Quapaw oral tradition recounts the immigration of their ancestors from the Ohio River Valley to the Arkansas River Valley where they displaced other tribes in the area. That tradition suggests that the Quapaw arrived in Arkansas between 1543, when the Hernando de Soto expedition left the area, and 1673, when the French first arrived.

Quapaw population figures differ greatly in the late seventeenth century and in the eighteenth century. Estimates range from 3,500 to 7,500. After the smallpox epidemic of 1698, population declined dramatically, numbering from 800 to 1,200. Quapaw population was estimated at the same level in the 1740s as in 1698 at the end of that year’s epidemic—about 1,200. From 1698 to the middle of the eighteenth century, epidemics and raids by other tribes, the Chickasaw particularly, severely depopulated the Quapaw. Epidemics of an unknown origin dragged the population down under 500 around the 1750s. It recovered again, growing up to 750, only to decline once more—and never to rise above 750 before the 1830s. By 1721, depopulation also led to the unification of two villages—Tourima and Tongigua. By that time, all of the villages were located on the Arkansas River in Desha County and Arkansas County.

At the time of the Louisiana Purchase, the Quapaw population stood at 555 in three villages located on the south bank of the Arkansas River. The first village, Kappa, under the tribe’s principal chief, Wah-pah-tee-see, had a population of 160; the second, Tourima, under Etah-sah, had a population of 166; the third, Osotouy, under Wah-to-nee-kah, was the largest with 229. By 1811, when the first U.S. census was taken, white settlers, 1,062 of them, outnumbered the Quapaw two-to-one. The wave of American immigration to Arkansas, while smaller than that coming into Missouri and Louisiana, overwhelmed them.

Like other Native American tribes, the Quapaw divided labor based on gender. Women were farmers and gatherers; men were hunters and warriors. Women farmed extensive fields that included maize, squash, beans, sunflowers, and many other plants and vegetables. Men hunted the abundant wild game, primarily deer, bears, and, into the early nineteenth century, bison. Quapaw hunting territory extended along the Arkansas River past present-day Little Rock (Pulaski County) and within the Grand Prairie. Later in the eighteenth century, the Quapaw were hunting to the west and southwest into the Ouachita basin.

Quapaw Indians intermarried with the French during the colonial period and were strong allies of the French. They fought with or supported the French in war and helped to defend the Mississippi River against the pro-British Chickasaw. Although France ceded their Louisiana colony, including Arkansas, to Spain in 1762, the Quapaw remained close to the remaining French colonists and became allies of the new Spanish colonial government.

In the 1780s, the Quapaw and Chickasaw agreed to peace. Over the next several decades, the Quapaw gave their blessings to the arrival of hunters and immigrants from the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Chickasaw tribes.

Quapaw involvement in local and regional trade continued into the territorial period. Corn, raised by Quapaw women, and horses, raised by both men and women, were traded to their white neighbors, as well as to hunters. Quapaw men also continued to hunt and to trade animal products. As long as the Mississippi River was a boundary and travel on it could be contested, the Quapaw were important to colonial diplomacy and defense. As the U.S. population grew, the Quapaw’s economic role diminished, and their land became more desirable to Americans. The Quapaw were not a priority for the United States as they had been for the French and Spanish. Once the United States united both banks of the Mississippi River with the Louisiana Purchase, however, the Quapaw no longer held a strategic position.

In an 1818 treaty, the Quapaw agreed to a reservation of one million acres running northeast to southwest between the Arkansas and Ouachita rivers. They relinquished their claims to thirty million acres south of the Arkansas and to the west in exchange for $4,000 in goods and an annual payment of $1,000 worth of goods.

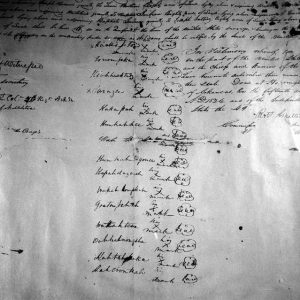

The 1818 treaty was not enough for settlers and territorial officials, who coveted valuable Quapaw land on the Arkansas River. These groups put pressure on the Quapaw, who signed the Treaty of 1824 and ceded their reservation to the United States. In return, they received land among the Caddo on the Red River in northwestern Louisiana, $4,000 in goods, and a $2,000 annual annuity for eleven years. The treaty also reserved land along the Arkansas River for eleven mixed-blood families.

The Quapaw moved to Caddo country in early 1826 but met with disaster. Flooding destroyed crops; starvation killed sixty people, including members of legendary Quapaw leader Sarasin’s family; and bureaucratic confusion undermined the Quapaw’s confidence in the federal government’s agents. After six months there, Sarasin broke with Heckaton, the principal chief, and led one-fourth of the nation back to the land reserved for him on the Arkansas River.

The federal government responded by awarding one-fourth of the Quapaw annuity to the Arkansas band but, in hopes of persuading Sarasin and his band to leave Arkansas again, prohibited them from using the annuity money to buy land. Many Quapaw became squatters on land near Pine Bluff (Jefferson County), farming and hiring themselves out to pick cotton and hunt game for white families. The Quapaw began to use the annuity to lay the foundation for a Quapaw future in Arkansas. They persuaded Governor George Izard to buy agricultural implements with the annuity and paid for ten Quapaw boys to go to school.

By 1830, all of the Quapaw had returned to Arkansas. Heckaton abandoned the Red River settlement and led the remnant of the nation back to the Arkansas River. Sarasin rejected government suggestions that his people join the Cherokee or the Osage, the latter of which he considered enemies of the Quapaw. He and Heckaton pleaded with federal and territorial officials to allow the Quapaw to remain in Arkansas. However, only Sarasin was promised that he could remain in the territory.

In 1832, the Quapaw finally received annuity payments that had been denied them for years. It was too little and too late. Unable to buy land, many Quapaw were pushed off their farms by white settlers, and some found refuge only in the swamps. With their situation becoming more desperate, the Quapaw signed the Treaty of 1833 by which they agreed to move to 150 sections (96,000 acres) in the northeastern corner of the Indian Territory.

Many did not go to the new reservation. Instead, Sarasin led 300 people back to the Red River, where the annuity had been sent. He soon returned to Arkansas and lived in Jefferson County until his death. Heckaton and 161 Quapaw meanwhile started the process of rebuilding their nation in the Indian Territory.

Today, most of the Quapaw Nation resides in northeastern Oklahoma with the tribal headquarters in Quapaw, Oklahoma. In 1956, the Quapaw Business Council succeeded the traditional leadership of chiefs as the tribal government. Elected by tribal members, the council includes a chairman, vice chairman, secretary-treasurer, and four council members. Under the federal Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), the Quapaw are recognized as one of the historic tribes of eastern Arkansas and are consulted on Arkansas archaeological sites related to Native Americans.

In 2014, the Quapaw Nation purchased 160 acres of land near the Little Rock Port Authority’s industrial park after learning of several hundred suspected graves of Native Americans on the property. Concerns about the use of the land were raised locally when the tribe submitted an application to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in late 2014 requesting that the land be given Federal Trust status. The main concern was the possibility, though denied by the Quapaw, that the land might be used for the establishment of a casino. By the spring of 2015, Pulaski County officials had filed a request with the Bureau of Indian Affairs to deny the request. In January 2019, the tribe reached an agreement with the Little Rock Port Authority to sell back the purchased land.

For additional information:

Arnold, Morris S. “The Métis People of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Arkansas.” Louisiana History 57 (Summer 2016): 261–296.

———. “Military Cooperation and the Relocation of Quapaw and French Settlements in Colonial Arkansas: A Case Study in Colonial International Relations.” Academic Papers (Arkansas Archeological Survey) 2003. Online at https://scholarworks.uark.edu/aas_ap/1/ (accessed January 18, 2024).

———.”The Quapaws and the American Revolution.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Spring 2020): 1–39.

———. The Rumble of a Distant Drum: The Quapaws and Old World Newcomers, 1673–1803. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2000.

Baird, W. David. The Quapaws: A History of the Downstream People. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980.

Cash, Jon D. “Removal of the Quapaw and Osage.” Arkansas Review: A Journal of Delta Studies 48 (December 2017): 163–179.

DuVal, Kathleen. “The Education of Fernando de Leyba: Quapaws and Spaniards on the Border of Empires.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 60 (Spring 2001): 1–29.

———. The Native Ground: Indians and Colonists in the Heart of the Continent. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

Jones, Linda C. “Language Encounters in Colonial Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 82 (Spring/Summer 2023): 23–27.

Key, Joseph Patrick. “An Environmental History of the Quapaws, 1673–1803.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 79 (Winter 2020): 297–316.

———. “Outcasts Upon the World: The Quapaws and the Louisiana Purchase.” In A Whole Country in Commotion: The Louisiana Purchase and the American Southwest, edited by Patrick Williams, S. Charles Bolton, and Jeannie M. Whayne. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2005.

———. “The Treaty of 1824 and the Expulsion of the Quapaws.” Pulaski County Historical Review 68 (Winter 2020): 94–99.

Nolan, Raymond Anthony. “Better Royalties: Federal Policy, the Quapaw Tribe, and Self-Determination.” Chronicles of Oklahoma 96 (Winter 2018-19): 428–444.

The Official Quapaw Website. http://www.quapawtribe.com/index.aspx (accessed August 11, 2023).

Sabo, George, III. Paths of Our Children: Historic Indians of Arkansas. Popular Series 3. Fayetteville: Arkansas Archeological Survey, 1992.

———. “Rituals of Encounters: Interpreting Native American Views of European Explorers.” In Cultural Encounters in the Early South: Indians and Europeans in Arkansas, compiled by Jeannie M. Whayne. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1995.

Joseph Key

Arkansas State University

Buffalo Dance

Buffalo Dance  Indian Extents Map

Indian Extents Map  Marquette-Joliet Expedition

Marquette-Joliet Expedition  Quapaw Man Mural

Quapaw Man Mural  Quapaw Treaty of 1824

Quapaw Treaty of 1824  Quapaw Tribe Visiting Site

Quapaw Tribe Visiting Site  Sarasin's Tombstone

Sarasin's Tombstone  Test Excavations

Test Excavations

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.