calsfoundation@cals.org

Edmund Hogan (1780?–1828)

General Edmund Hogan was an imposing figure in territorial Arkansas. A veteran of the War of 1812, Hogan was one of the first settlers in Pulaski County, the leader of the territorial militia, and a legislator. His penchant for lawsuits and disputes rivaled his successes, resulting in a fatal encounter with a political foe.

Born about 1780, possibly in Anson County, North Carolina, to Griffin and Mary (Gibson) Hogan, he spent his early years in Laurens County, Georgia. He was a tax collector, sheriff, state legislator, and a lieutenant colonel in the Georgia militia. By 1814, he had resigned his military commission and moved to Arkansas.

Around 1803, Hogan married Frances Jane Green, born about 1780 in Pulaski County, Georgia. The Hogans had six children: William, James, John H., Nancy, Frances Jane, and Elizabeth. His wife died between 1815 and 1820. He then married Lucinda Greathouse, with whom he had three children: Woodson, Gabriel, and Almarine.

Hogan represented Arkansas in the Territorial General Assembly of Missouri in 1816 and 1818, when Arkansas was part of the Missouri Territory. When Pulaski County was created in 1818, he was its first justice of the peace and later first postmaster of Crystal Hill (Pulaski County).

Hogan was one of the first to operate a ferry directly across from la petite roche, or “the little rock,” a strategic spot on the Arkansas River. Naturalist Thomas Nuttall visited Hogan on trips through Arkansas Territory in 1819 and 1820 and wrote of Hogan’s place as the “settlement of Little Rock.” His home became a meeting place and temporary home for early settlers like William Lewis and William Mabbitt. The ferry was later owned by first territorial secretary Robert Crittenden.

On March 21, 1821, President James Monroe issued an executive order appointing Hogan as brigadier general of the militia of Arkansas. Many in his command were veterans, characterized by author Josiah Shinn as “free and easy in their manners, outspoken in their conversation and therefore very hard to control.” Hogan had “considerable force of character, and being a superior soldier managed to control the combustible elements of which the militia was formed at that time, and to make of them most serviceable soldiers.” He was also an imposing physical presence at well over six feet tall and weighing more than 200 pounds.

Hogan was also involved in various legal disputes. He had disagreements with Lewis Bringier over Crystal Hill property; won a libel suit against William Russell, who accused Hogan of making illegal political deals; was involved in complex financial dealings with William Drope and John Miller; testified for William Flanakin, who was sued for the return of a slave in Lanusse v. Flanakin; and sued William E. Woodruff, administrator of the estate of Nathaniel Philbrook, for damages in Hogan v. Woodruff.

Hogan was also involved in a bitter political contest in 1825, when he ran against Colonel Alexander S. Walker for a seat on the Territorial Legislative Council. Hogan was declared the winner by a narrow margin, but Walker ordered and won a new election, which was overturned. The contest divided the citizenry and created hard feelings between candidates.

In 1827, Hogan and Walker were again rivals for a seat, along with a third candidate, Judge Andrew Scott, himself no stranger to controversy. Scott’s campaign likely suffered because he had killed Judge Joseph Selden in a duel, and the 1827 campaign was more heated than the previous election. Hogan won, but bitter feelings remained.

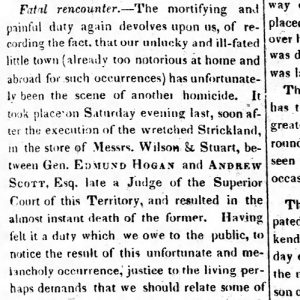

“Our unlucky and ill-fated little town (already too notorious at home and abroad for such occurrences), has unfortunately been the scene of another homicide,” the Arkansas Gazette editorialized about Hogan and Scott’s final, fatal encounter on May 31, 1828. The pair met at the store of Wilson & Stuart, following a public hanging. Both men appeared to be in good humor, the paper reported, until conversation turned to the election, which produced “a few warm words” between them. As the newspaper reported, “Gen. Hogan asserted something, which was denied by Judge Scott, on which H. repeated the assertion, and remarked that he could prove it. Judge S. replied, in substance that the assertion was untrue, that it could not be proved, and that any person who made it was a LIAR! This reply was followed by a blow from H. which felled S. to the floor, who, in rising, drew the spear from his cane and gave H. four stabs in the breast and sides, 3 of which were mortal. Hogan walked to the door, commenced vomiting blood, and was a corpse in less than ten minutes.”

Scott was arrested, but no charges were filed. Reports of the incident appeared in newspapers across the country, including Rhode Island’s Cadet & Statesman, the Baltimore Gazette & Daily, New York’s Commercial Appeal, and the National Gazette.

Hogan’s actual burial site is the subject of conjecture. Some historians believe he may have been interred at Crystal Hill or Mount Holly Cemetery, but Goodspeed’s Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Central Arkansas reported his original burial site as the ground overlooking the Arkansas River where the Old State House now stands. Goodspeed’s reported that when an excavation was made in 1885 for improvements to the Old State House, three or four graves were found, containing the remains of Gen. Hogan, his wife Frances, and possibly their children Nancy and James. The bones were then said to have been disinterred and placed in the cornerstone of the new addition.

For additional information:

Goodspeed’s Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Central Arkansas. Chicago: Goodspeed Publishing Co., 1890.

Nuttall, Thomas. A Journal of Travels into the Arkansas Territory during the Year 1819, edited by Savoie Lottinville. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1980.

Paige, Amanda L., Fuller L. Bumpers, and Daniel Littlefield Jr. “The North Little Rock Site on the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail: Historical Contexts Report.” 2003. American Native Press Archives. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Shinn, Josiah Hazen. Pioneers and Makers of Arkansas. Vol. 1. Baltimore: Genealogical and Historical Publishing Company, 1908.

Dana Gieringer

Fayetteville, Arkansas

It appears Hogan was in Missouri Territory and probably the Little Rock area before 1814. According to Margaret Ross Smith in the Pulaski County Historical Review: “It is not known how long before 1814 Hogan lived opposite Little Rock, but he was probably here at least as early as 1812. In 1797 he had a farm opposite Thebes, Illinois….We follow him from there to the District of Cape Girardeau, Louisiana Territory, where he was appointed justice of the peace on July 8, 1806.” He is listed among the heads of households in the Cape Girardeau District of the Louisiana Territory at the time of the Louisiana Purchase. Records indicate that his eldest daughter, Nancy, was born in Little Rock in 1811. He was appointed captain of the 1st Company of the 2nd Battalion of the 7th Regiment (Arkansas County) of the Missouri Territorial Militia on June 23, 1814. On December 17, 1814, he signed a petition to Congress along with several others stating that they had been mustered into service as part of the Missouri Ranger Companies on May 20, 1813, and had been discharged three months later, without being paid. Hogan is technically a veteran of the War of 1812, as all members of the militia from that period are recognized as veterans, but it appears that his only active service during the war was the three months he spent in the Missouri Rangers. His appointment as a brigadier general probably had more to do with his prominence as an earlier pioneer, wealthy landowner, and legislator than with his war record. This also calls into question achievements generally attributed to him in Georgia. Most family records place his birth as approximately 1780. He is clearly in Missouri by 1803, meaning he had served as legislator, sheriff, and lieutenant colonel at an impossibly young age.

Following the War of 1812, Hogan filed a claim for payment that is on file with the Missouri Secretary of State. That claim lists his unit as Company 1st Company, 2nd Battalion, 7th Regiment of Missouri Regiment.