calsfoundation@cals.org

Brooks-Baxter War

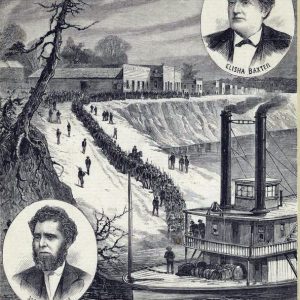

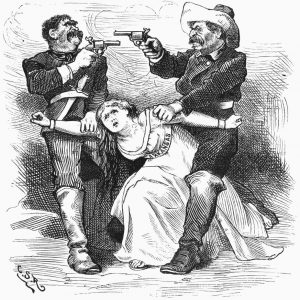

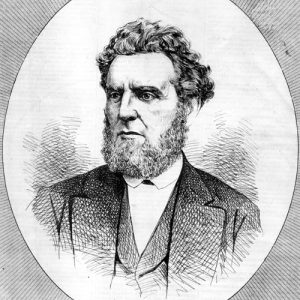

The Brooks-Baxter War, which occurred during April and May 1874, was an armed conflict between the supporters of two rivals for the governorship—Joseph Brooks and Elisha Baxter. The violence spilled out of Little Rock (Pulaski County) into much of the state and was resolved only when the federal government intervened. The result of the war, recognition of Elisha Baxter as the governor, brought a practical end to Republican rule in the state and thus ended the era of Reconstruction.

Questions concerning the results of the state’s 1872 gubernatorial election brought about the Brooks-Baxter War. In that election, Joseph Brooks—a carpetbagger with a radical reputation and the leader of the party faction known as the “Brindletails”—ran as a Reform Republican, supporting the national Liberal Republican movement, including Horace Greeley for president, and advancing a local plan to end the disfranchisement of former Confederates, reduce taxes, cut government expenses, and limit the power of the governor. His program attracted conservative Republicans and Democrats, who saw his programs as the best way for them to recapture power and backed him despite his radical past. Republican regulars, often called “Minstrels,” backed Elisha Baxter, a scalawag who ran on a platform promising many of the same reforms proposed by Brooks. Central to the campaign was the issue of disfranchisement and the ability of the Minstrels to maintain control of the state government. Brooks may actually have won the subsequent election, but Baxter’s supporters controlled the election machinery and declared Baxter and other regulars victors, despite evidence of widespread irregularities. Brooks and his supporters refused to accept the results. They appealed the seating of the regular party’s candidates in Congress and secured one seat for a pro-Brooks candidate. Brooks also appealed the gubernatorial election to the legislature, but the legislature refused to hear his case.

The Arkansas General Assembly’s failure to act on Brooks’s appeal did not settle the dispute, and he continued his efforts to displace Baxter, taking his dispute to the state courts. His legal appeals failed until changing political circumstances and shifting alliances created a court favorable to his position. The new condition was the regular Republican leaders’ loss of faith in Baxter, who not only tried to get former Democratic leaders to support him but adopted a hostile attitude toward one of the Republican Party’s major economic programs—state aid to railroads. Shortly after Baxter refused to sign bonds designated for the Arkansas Central Railroad and raised questions about the legality of all railroad bonds, Republican regulars, including U.S. senators Powell Clayton and Stephen Dorsey, met in Little Rock and determined to remove the governor. After that meeting, the Pulaski County Circuit Court of Judge John Whytock took up a request by Brooks for a writ giving him possession of the governor’s office that had languished since June 1873. On April 15, 1874, Whytock ruled in favor of Brooks and issued the writ.

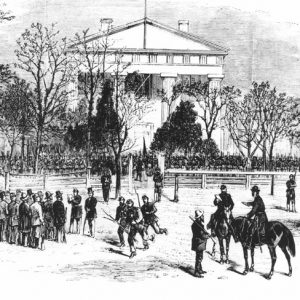

Brooks acted quickly and marched to the State House with a group of armed men and the Pulaski County sheriff. Confronting Baxter, the sheriff demanded that the governor leave his office. Alone except for his young son, the governor left under protest. Baxter immediately went to St. Johns’ Military Academy, where he began to gather his supporters and telegraphed President Ulysses S. Grant, requesting support from U.S. forces at the Little Rock Arsenal in his efforts to retake his office. By the next morning, he had gathered 200 men, and they moved to the Anthony House, just east of the capitol, and began to prepare to recapture the State House by force. From the Anthony House, Baxter proclaimed martial law in Pulaski County, naming Thomas P. Dockery military governor of Little Rock, and called on the state militia for support.

Brooks, in turn, fortified the State House, using furniture to barricade windows and doors. Brooks’s adjutant general, Robert F. Catterson, broke into the state armory to obtain equipment and ammunition for his men. In addition, Catterson acquired two six-pounder artillery pieces that he placed on the capitol grounds, aimed at the Baxter men in the Anthony House. Brooks also called on militia companies for support.

The two governors had earlier stated their intention to hold on to their office even if it required the shedding of blood. The rapid gathering of large groups of armed men in Little Rock practically guaranteed that. After the call for support by the two parties, military companies loyal to one or the other began arriving. By April 20, Baxter’s men numbered more than 1,000, and Brooks had mustered almost as many. By that day, Baxter’s supporters indicated that they were ready to move against the State House. With orders from Washington DC to prevent a clash, Colonel Thomas E. Rose, commander at the arsenal, deployed U.S. regulars from the Sixteenth Infantry plus two pieces of artillery on Markham Street between the contending parties. Rose indicated his willingness to use force quickly. On the evening of April 21, after believing he had secured a twenty-four-hour truce, Rose confronted H. King White, who had arrived with Baxter supporters from Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) outside the Anthony House. Rose believed White was intent on inciting a riot. In the confrontation, someone fired a shot. In the resulting confusion, more shots were fired, producing several casualties. Rose returned to his troops, cleared the street, and threatened to open fire on the crowd. The next day, federal troops began building a barricade between the two sides to prevent further bloodshed.

Baxter responded to the intervention of the army with a complaint to Grant that its presence prevented him from reclaiming his office. The federal force’s actions also may have convinced him that violence would not regain him his office. On April 22, he informed Grant that he intended to call the legislature into session to settle the rival claims. The same day, Grant replied that he approved any peaceful solution. The war continued, but after April 22, the real struggle for the office shifted to Washington DC. The last week of April, Attorney General George H. Williams began meetings with representatives of the two factions in Washington. Prominent Little Rock attorney Uriah M. Rose, along with Albert Pike and former senator Robert W. Johnson, presented the case for Baxter. Senators Clayton and Dorsey represented Brooks.

In Arkansas, each contender kept his military force intact while events moved along in Washington, although their activities tended to center on preventing the other side from being reinforced. White was given command of Baxter’s forces at Pine Bluff, and from that base, he repeatedly intercepted men trying to get to Little Rock to aid Brooks. On April 30, he intercepted a contingent of African-American troops near New Gascony in Jefferson County. In the clash that followed, his men killed nine and wounded twenty of the troops. On May 1, White dispersed Brooks supporters in Lincoln and Arkansas counties, and two days later, they fought another battle near Arkansas Post (Arkansas County), killing five more men. Several other confrontations would occur, with skirmishes on May 8 at Lonoke (Lonoke County) and at the mouth of Palarm Creek, where Baxter’s troops tried to stop delivery to Brooks of a shipment of weapons taken from Arkansas Industrial University—now the University of Arkansas (UA) in Fayetteville (Washington County). Later estimates put the number killed in all of these confrontations at more than 200.

At Little Rock, the situation also remained tense. Baxter’s supporters dug up a buried Civil War sixty-four-pounder cannon, repaired it, named it the “Lady Baxter,” and used it to threaten the opponent. One of Baxter’s commanders, Thomas J. Churchill, kept the Brooks forces on edge with periodic orders for residents around the Lady Baxter to move out in preparation for a bombardment. As the Grant administration considered the problem, each side also maneuvered to improve its position. Serious skirmishing took place on May 12, when Baxter forces tried to secure a position north of the Arkansas River, only to be forced back by U.S. troops.

The beginning of the end came on May 9 in Washington, when representatives of Baxter and Brooks met with the attorney general. All agreed that a special legislative session should settle the issue. On May 10, Baxter and Brooks agreed, although Baxter replied that he saw no reason for a special session because he had already called the legislature into session. Attorney General Williams agreed, but Brooks objected and declared he would not abide by any decision of the legislature. Seeing that there could be no compromise, Grant now asked his attorney general for a decision on who should be governor. After having heard the cases of the contending parties, Williams issued his opinion May 15. He said Baxter was the legal governor. That day, the president issued a proclamation indicating that because the legitimate government of Arkansas, Baxter’s, had asked for federal aid in suppressing insurrectionary forces, he would provide assistance and ordered all those opposed to the existing government to disperse.

With no hope of support from Washington, Brooks disbanded his forces. He and his men began moving out of the State House. Many, fearing retribution, fled the city or hid from their opponents. Indeed, for a time, Baxter considered prosecuting many of his opponents for treason. On May 19, Baxter returned to the State House, and his supporters staged a victory parade. Grant had ended the “war,” and Arkansas once again had only one governor. The era of Reconstruction had come to an end.

For additional information:

Atkinson, James H. “The Arkansas Gubernatorial Campaign and the Election of 1872.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 1 (Winter 1942): 307–321.

Christ, Mark K., ed. A Confused and Confusing Affair: Arkansas and Reconstruction. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2018.

DeBlack, Thomas A. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Harrell, John M. The Brooks and Baxter War: A History of the Reconstruction Period in Arkansas. St. Louis, MO: Slawson Printing, 1893. Online at https://archive.org/details/brooksbaxterwarh00harr/page/n3/mode/2up (accessed March 6, 2024).

Ownings, Richard. “The Brooks-Baxter War.” Arkansas Times, May 1980, pp. 41–48.

Smith, John I. Forward from Rebellion: Reconstruction and Revolution in Arkansas, 1868–1874. Little Rock: Rose Publishing Company, 1983.

Stafford, Logan Scott. “Judicial Coup D’état: Mandamus, Quo Warranto and the Original Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of Arkansas” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 20, no. 4 (1998): 891–984. Online at https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/lawreview/vol20/iss4/3/ (accessed August 23, 2023).

Tricamo, John. “The Brooks-Baxter War.” MA thesis, Fordham University, 1952. Selection online at https://research.library.fordham.edu/dissertations/AAI28509507/ (accessed January 30, 2026).

Woodward, Earl F. “The Brooks and Baxter War in Arkansas, 1872–1874.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 30 (Winter 1971): 315–336.

Carl H. Moneyhon

University of Arkansas at Little Rock

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.