calsfoundation@cals.org

Climber Motor Corporation

The automobile craze grew by leaps and bounds during the early twentieth century. A 1907 issue of Outing Magazine reported that “In 1906, the cost of the annual American output of automobiles was $65,000,000. There were 146 concerns in business, which represented a capitalization of probably $25,000,000 and were giving employment directly and indirectly to an army of men which reached well up into the hundreds of thousands.” Arkansas was in no way left behind by the explosive growth of the use of the automobile. By 1913, there were 3,596 registered passenger vehicles in Arkansas.

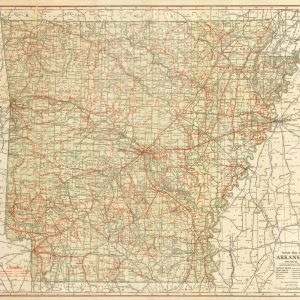

Even though automobile production was growing year by year, the improvement of roads to accommodate the new vehicles was severely lagging behind across the nation, including Arkansas. Even after the passage of Act 302 in 1913, which established the State Highway Commission and the State Department of Transportation as affiliates of the Department of State Lands, it was many years before anything resembling a good system of improved roads was in place. As a result, automobile travel around the state was an arduous task at best in the early years.

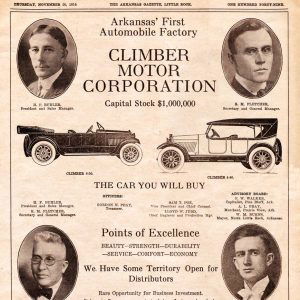

The Climber Motor Corporation, Arkansas’s only automobile manufacturer, produced cars and trucks that would cope with Arkansas’s primitive road system better than previous modes of transportation. In Little Rock (Pulaski County), William Drake, Clarence Roth, and Davis Hopson incorporated the Climber Motor Corporation in early 1919. They envisioned a car that could drive well on pavement as well as on unimproved roads and that could handle the terrain of the Ozark Mountains as well as the flat, straight stretches of road found in the Delta.

The company’s first board of directors consisted of Drake as president, Roth as vice president, and Hopson as secretary-treasurer. A reorganization in October 1919 (possibly due to constant financial problems and trouble getting parts for production) resulted in Henry Buhler, the general sales manager, being promoted to president. Lloyd Judd became treasurer, and Richard Fletcher became secretary and plant manager, while Roth remained vice president. Drake and Hopson both left the company.

To build its first factory, the company purchased a 20.46-acre site at 1823 East 17th Street in Little Rock for $20,460 from the Industrial Land Company. The site was ideal because it was far from the city’s residential areas and was already served by spur tracks of the Rock Island and Missouri Pacific railroads.

Factory construction began on January 9, 1919, with the truck department being the first building built. (Several other buildings were planned but were never constructed.) The factory was finished later in 1919. At the same time, the board began raising capital, finding skilled labor, and obtaining parts and materials. The search for skilled labor took board members to other parts of the country, and they succeeded in bringing people to work in the factory. George Schoeneck, a Detroit automotive engineer, became chief engineer. His contract called for the production of fifty four-cylinder cars.

Schoeneck’s main responsibility was to obtain the materials and parts needed to build the Climber in time to begin production in early 1919. Schoeneck traveled to the northern and eastern United States in early 1919, purchased all of the materials, and shipped them to Little Rock.

Although Schoeneck mistakenly thought he had enough materials, Climber production got off to a rocky start. The factory was constantly dealing with a parts shortage, and Schoeneck had to resort to designing and making his own parts. By the time the company was reorganized and President Drake retired in October 1919, cars were being produced at a rate of two a day, which would rise to five a day by the end of the month. All of the production problems were overcome in early 1920.

A chronic shortage of money also plagued the company. Initially, the company was capitalized, or allowed to issue stock valued at $1 million, with stock being sold to the public for ten dollars a share. Although the initial stock offering brought in enough money to allow production on a limited scale, financial problems soon developed. As a result, Buhler started an intensive advertising campaign to promote the Climber and boost stock sales.

Unfortunately, the stock campaign did not bring the desired results, and Buhler turned to the Chicago firm of Mintie, Myer, and Burns, Inc. for help in selling the stock. The stock would have to be offered at $17.50 a share, a price well above the legal limit of $12.50, to cover the firm’s costs and give ten dollars to the Climber Corporation. Buhler finally acquiesced and cosigned $300,000 worth of Climber stock to the firm, agreeing to sell it at $17.50 a share. Because the country was in the grips of the 1921 financial recession, however, the stock did not sell, and the continuing insurmountable financial problems would soon close the Climber Corporation.

In February 1924, the Pulaski County Chancery Court heard the Climber Corporation’s bankruptcy action. The company was declared bankrupt and put under the control of a receiver. On March 17, 1924, the receiver, X. O. Pindall, sold all of the Climber holdings, and the company closed. Total production for the Climber Corporation was approximately 200 cars and approximately seventy-five to 100 trucks.

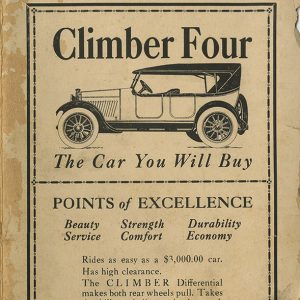

Although the company was constantly plagued by a lack of funds, and also a lack of parts, in its early days, the cars and trucks that the company produced were good vehicles. The company produced two car models, the Climber Four and the Climber Six, and at least two truck models, in one- and two-ton versions. The Climber Four, which was called the Climber “Four-Forty” in advertisements because of its four-cylinder, forty-horsepower Spillman engine, was a five-passenger touring car with a collapsible top and side curtains. The bodies were built of twenty-gauge rolled steel mounted over a wooden frame and initially came in three color patterns: dark maroon body, black hood, and cream wheels; black body, dark green hood, and red wheels; and battleship-gray body, black hood, and white wheels. Later models came in solid colors, either brown, black, or Brewster green. Upholstering and seat covers were Wilson and Company’s shrunk split leather, and each car came with a set of tools that included a pump, a jack, a set of tire tools, a set of six wrenches, a pair of pliers, a screwdriver, and a tool bag.

The Climber was also a durable automobile that could handle the rough roads of Arkansas at the time. To publicize the car’s abilities, an endurance test was conducted in the winter of 1919–20 under the supervision of William B. Owen, state highway commissioner. After the car’s engine was started in Little Rock, it was kept running constantly as the car traveled through 20,239 miles of “winter mud and rain over nearly impassable roads of the South.” The test ended on the grounds of the Arkansas State Capitol when Governor Charles H. Brough disconnected the car’s carburetor, shutting off the engine. The toughness of the Climber was illustrated in another test when the car was driven up the steps of the State Capitol. One early advertisement for the company also specifically targeted Arkansans when it said, “You believe in Arkansas. You live in Arkansas. The Climber Four is made in Arkansas for Arkansas roads. Buy a Climber Four and save the freight.”

In addition to the lack of parts and lack of capital that greatly plagued the Climber Corporation’s ability to produce the cars, the car’s expensive price ($2,250 for a Climber Six) did not help matters, especially in Arkansas, which was not a wealthy state. (By comparison, a Ford Model T cost $355 in 1920 and $290 in 1926.) As a result, in 1922, there were only ninety-six Climber passenger cars and eight Climber trucks licensed in Arkansas, while there were 43,772 licensed Ford passenger cars and 5,205 licensed Ford trucks. In 1923, the number of Climber cars licensed in Arkansas dropped to ninety-four and dropped again to ninety-one in 1924. The number of Climber trucks licensed in Arkansas remained at eight in 1923 but dropped to six in 1924. (At the same time, the number of Fords exploded, reaching 65,914 licensed cars in Arkansas in 1923 and 85,529 cars in 1924. Ford trucks numbers also grew tremendously, with 8,167 trucks licensed in 1923 and 13,347 licensed in Arkansas in 1924.)

Today, the Climber Motor Corporation factory building remains in Little Rock and is currently the headquarters of Creative Engineering/Micro Grinding. The significance of the building was recognized with its nomination to the National Register of Historic Places in 2005. In addition, two Climbers are known to exist, both located at the Museum of Automobiles outside Morrilton (Conway County).

For additional information:

Climber Motor Corporation Collection (BC.MSS.12.47). Butler Center for Arkansas Studies. Central Arkansas Library System, Little Rock, Arkansas. Finding aid online at https://cdm15728.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/findingaids/search/searchterm/mss.12.47 (accessed April 12, 2024).

Faulkner, Ed. “The Climber: A Chapter in Arkansas Automotive History.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 29 (Autumn 1970): 215–225.

Wilcox, Ralph S. “Climber Motor Car Factory.” National Register of Historic Places registration form, 2005. On file at Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, Little Rock, Arkansas. Online at https://www.arkansasheritage.com/arkansas-historic-preservation-program (accessed April 12, 2024).

Ralph S. Wilcox

Arkansas Historic Preservation Program

Arkansas Climber

Arkansas Climber  Arkansas Road Map, 1918

Arkansas Road Map, 1918  Climber Advertisement

Climber Advertisement  Climber Advertisement

Climber Advertisement  Climber Automobile

Climber Automobile  Climber Motor Corporation Ad

Climber Motor Corporation Ad  Climber Manufacturing Building

Climber Manufacturing Building  Climber Postcard

Climber Postcard  Climber Stock Certificate

Climber Stock Certificate

According to the Little Rock City Directory, 1922, John S. M. Cannon was the Secretary/Treasurer of the Climber Motor Corporation in 1922. The 1920 census lists him as the bookkeeper.