calsfoundation@cals.org

Apple Industry

Seventy-five years after their introduction in Arkansas, apples became a dominant agricultural crop and an economic engine for the northwest part of the state. However, their importance declined measurably in the last half of the twentieth century.

The apple of commerce, Malus domestica, is not native to North America. It is a complex hybrid of Malus species with origins in Asia and Europe. Malus domestica was introduced to North America by sixteenth-century explorers and later by colonists. Settlers arriving in Arkansas from Tennessee, the Carolinas, and Georgia brought apple seeds and scion wood with them. The Arkansas Gazette reported in 1822 that apples were being grown on the farm of James Sevier Conway west of Little Rock (Pulaski County). While apples are grown throughout the state, the Ozark Plateau region of northwest Arkansas was particularly suited for their culture. This area became the dominant region for apple production.

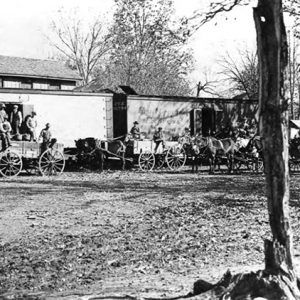

The influx of settlers into the Washington County area of northwest Arkansas was of such a magnitude that the U.S. government was forced to abrogate the Lovely Treaty of 1817, which gave this land to the Cherokee. Most homesteads had kitchen orchards for family use. Nurseries were established at Cane Hill (Washington County) in 1835 and at Bentonville (Benton County) in 1836 to meet the need for apple trees; others followed. Excess production from expansion of kitchen orchards was sold to freighters who hauled apples to distant markets in open wagons. In 1852, a wagon train to Van Buren (Crawford County) delivered apples to be sent by boat to Little Rock.

What is considered the first commercial apple orchard in the state was planted by a Cherokee woman near Maysville (Benton County); when forced to free her slave labor after the Civil War, she was unable to continue with the orchard. Other commercial orchards were planted in the 1870s. These orchards, frequently planted on land exploited by years of corn and tobacco, increased in size and number; by 1880, apple production exceeded what freighters could haul, and most of the crop was wasted. The expanding “Apple Belt of the Ozarks” had become a production area isolated from markets because it was devoid of sufficient transportation access.

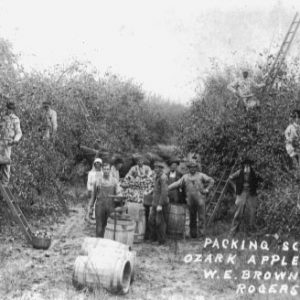

The entry of railroad lines into the state—such as one that reached Fayetteville (Washington County) in 1881 and Lincoln (Washington County) in 1901—offered access to distant markets as far as Maine and Saskatchewan, Canada. These new market outlets ultimately resulted in a massive increase in commercial orchard plantings in northwest Arkansas from 1880 to 1920. Acreage grew from a few hundred acres to many thousands, which by 1900 amounted to an estimated 40,000 acres in Benton County, based on tree counts, with only slightly smaller acreage in Washington County, thus making them the two largest apple-producing counties in the United States. The railroads enthusiastically and with optimism promoted opportunities for easy profit making, and for a few years, this was true. Along with the great orchard expansion, supporting industries developed: barrel making, apple drying, distilling juice, packing sheds, and ice-making plants.

Barrels, manufactured locally, held 140 pounds of fruit and were packed for shipping in the orchard. As late as 1919, sixty percent of the crop was packed in barrels and shipped as green apples, although switching to boxing had been advocated some ten years earlier. The apple-drying business, utilizing low-grade fruit, became the largest employer in the area by 1901. An estimated 250 evaporators were in existence, with the largest being the Kimmons-Walker Plant located in Springdale (Washington County). The 1906 Wiley Pure Food Act seriously curtailed this heretofore unregulated business; by 1920, drying was an almost extinct business. In 1895, there were forty-seven distilleries operating in the area producing brandy and vinegar. The O. L. Gregory Plant was located in Rogers (Benton County). When an ice-making plant was built in Fayetteville in 1895, it provided a cold storage facility and ice for rail shipping.

Arkansas Industrial University (now the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville) established experiments in scientific horticulture and its teaching, thus becoming an important asset to the apple industry, a role it continues today. Its first bulletin in 1886 dealt with apples. The Arkansas State Horticultural Society, catering primarily to apple growers since 1900, held annual meetings in various locations in the area for discussion and dissemination of knowledge in orchard culture. Apple varieties played a significant role in the successes and failure of the orchard industry. The Ben Davis variety, introduced from Tennessee, was the leading variety grown from 1889 to 1930, although it was not recommended for planting after 1905 because of its poor eating quality and a low price return to growers. These and other inferior grade apples were dried or processed into vinegar. Seedling varieties selected by growers and nurserymen played a significant role in production. Over fifty were named but had only local name recognition; among them were the Shannon Pippin, Ada Red, Red Streak, Etris, Gano, and Coffelt. The Arkansaw (or Mammoth Black Twig) and the Arkansas Black were the most well known.

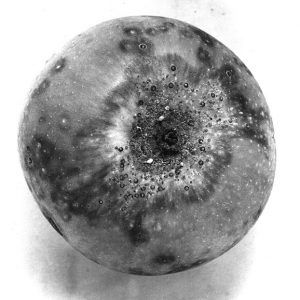

The emerging apple economy in the early years of the 1900s was not able to sustain itself. From a crop of over three million bushels in 1906 to record production of over five million bushels in 1919, production declined steadily to less than two million bushels in 1935 to crops of less than 250,000 bushels by the 1960s. Indications of the decline were apparent even before the apple industry peaked in 1919. Among the numerous reasons for the decline were poor varieties, namely the Ben Davis, but also mixing little-known seedling selections in car lot loads; a growing reputation for shipping poor-quality fruit; and the consequences of an expanding monoculture resulting in increases in insect and disease pressure. Diseases such as fire blight (a bacterial disease native to North America and particularly destructive to apple trees) and Cedar Apple and Apple Scab fungal diseases—common in Arkansas orchards after the 1880s—coupled with insects such as the codling moth, introduced from England, and the San Jose scale, introduced from China, seriously hampered apple growing. These factors greatly reduced the profitability in apple growing enjoyed in earlier years. Other contributing factors include a failure to adapt to changing market demands, federal regulations, occasional crop failures, disparate shipping rates favoring West Coast apple regions (after the opening of the Panama Canal), the aging of orchards, and the Great Depression and Dust Bowl years of the 1930s.

By resolution of the Arkansas General Assembly in 1901, the apple blossom was declared the state flower. This followed an impassioned plea by Love Barton, a woman from Searcy (White County), who presented each assembly member with a bright red apple. Apples were customarily exhibited at local, national, and international exhibits. An exhibit of Arkansas apples won first prize at the Centennial Fair in Philadelphia in 1876. In 1900, the Arkansas Black variety won first prize at an exhibition in Paris, France. Arkansas apples exhibited at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1905 won in all major categories. According to the Arkansas Sentinel, a fair in Springdale saw over 140 seedling entries, and the top award went to the Mammoth Black Twig. The prize was ten dollars.

The first Rogers (Benton County) Apple Blossom Festival was held in 1923 and featured a parade with floats from schools, clubs, civic organizations, and businesses. The 1926 festival drew over 30,000 people, many brought to Rogers from adjacent cities by special trains. The festivals were canceled after 1927 because of frequency of rain periods during bloom season. From 1932 to 1942, the South West Times Record of Fort Smith (Sebastian County) sponsored apple blossom pilgrimages. The paper distributed road maps to orchard locations. Over 1,080 automobiles were counted passing a checkpoint near Rogers in 1934, and 540 cars from Fort Smith made the trip on Highway 71. The town of Lincoln revived the festival feature and has had a fall Arkansas Apple Festival every year since 1976. In recent years, the arts and crafts aspect of the festival has over-shadowed Lincoln’s once prominent position in the apple industry.

The apple industry will never return to the prominence it had at the beginning of the twentieth century. Conditions of the world economy at the beginning of the twenty-first century dictate this. Fewer than 150 growers in the state sell apples in the twenty-first century, with an average orchard size of less than five acres. These are mostly located adjacent to towns in the northern half of the state. While the trend is to grow some of the newer varieties, Jonathan, Golden Delicious, Red Delicious, and Gala types are the principal cultivars grown.

Local farmers’ markets, roadside stands, and sales on premises also offer an opportunity to fill a niche and profitably sell orchard-fresh, high-quality fruit of specific varieties direct to the consumer. The fruit is generally grown utilizing integrated pest management (IPM) practices or following Certified Organic Production protocols.

For additional information:

“Apple Varieties that Originated in Arkansas.” Flashback 12 (September 1962): 23–26.

Black, J. Dickson. History of Benton County. Little Rock: International Graphics Institute, 1975.

Brown, C. Allan. “Horticulture in Early Arkansas.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 43 (Summer 1984): 99–123.

Camptell, W. S. “Rise and Fall of Apple Empire.” Flashback 11 (February 1961): 29–33.

Forman, E. S. “Advantages of Growing Fruit Along the St. Louis and North Arkansas Rail Roads.” Arkansas State Horticultural Society Proceedings, 1904, pp. 75–80.

Logan, J. P. “Horticulture in Arkansas Now and 25 Years Ago.” Arkansas State Horticultural Society Proceedings, 1902, pp. 35–40.

McColluch, Lacy P. “Apple Industry at Cane Hill.” Flashback 16 (October 1966): 1–2.

Nowlin, S. H. “Annual President Address.” Arkansas State Horticultural Society Proceedings, 1900–01, pp. 1–7.

———. “History of Fruit Growing in Arkansas.” Proceedings of the 28th Session of the American Pomological Society, 1905, pp. 81–83.

Owens, Nathan. “Apples Still Appealing for Nostalgic Few.” Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, July 30, 2017, pp. 1G, 8G.

Walker, E. “Address to Society.” Arkansas State Horticultural Society Proceedings, 1909, pp. 102–117.

Roy Curt Rom

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.