calsfoundation@cals.org

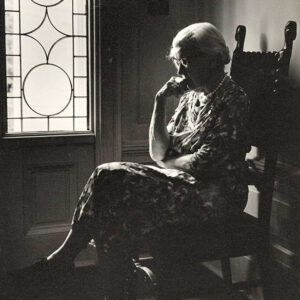

Adolphine Fletcher Terry (1882–1976)

Adolphine Fletcher Terry was a civic-minded woman from a prominent Little Rock (Pulaski County) family who used her position to improve schools and libraries, start a juvenile court system, provide affordable housing, promote the education of women and women’s rights, and challenge the racism of the Old South. Terry pushed for social change in the early years of the civil rights movement and may best be known as the leader of the Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools (WEC).

Adolphine Fletcher was born on November 3, 1882, in Little Rock to John Gould Fletcher and Adolphine Krause Fletcher. Her father worked in the cotton business and in banking and served terms as sheriff of Pulaski County and city mayor. She was the oldest of three children. Pulitzer Prize–winning poet John Gould Fletcher Jr. was her younger brother.

With her mother’s encouragement, Fletcher enrolled in Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, when she was fifteen. Her East Coast education and schoolmates broadened her views on race relations. She graduated in 1902, at a time when few men and even fewer women had college degrees.

Fletcher’s father died in 1906, and her mother died three years later.

After college, Fletcher and another Vassar graduate from Arkansas, Blanche Martin, were asked to serve on a national committee to investigate the state’s educational needs. They discovered a system of mostly one-room schoolhouses among 5,000 school districts, inadequate supervision, and no consistent policies. The two made school consolidation their cause, writing articles for newspapers, making speeches, and lobbying. In 1908, Fletcher was leading efforts to consolidate school districts, appoint professional county superintendents, and provide school transportation in rural Arkansas.

As a young college graduate, Fletcher also co-founded a group to encourage women to become college educated. The group eventually became the Little Rock branch of the American Association of University Women. She also formed the first School Improvement Association in Arkansas, forerunner of the Parent Teacher Association; organized the first juvenile court in Arkansas in 1910; and chaired the Pulaski County Juvenile Court board for about twenty years. She helped start the Girls Industrial School near Alexander (Pulaski and Saline Counties) for girls detained by the court, as well as a temporary home for young people who had no adult supervision.

On July 7, 1910, Fletcher married Little Rock native and lawyer David D. Terry. The couple had four children: David, Mary, Sarah, and William.

Mary Terry was born in 1914 with a rare condition, called osteogenesis imperfecta, that caused her bones to break for no apparent reason. The condition crippled Mary for life and had a significant impact on her mother. Despite doctors’ predictions, Mary lived a long life, earned a college degree, traveled, and had a career in psychological testing. Terry said caring for Mary led to an awakening in which she found “in some measure the spiritual meaning of life, a sense of real achievement and peace.”

Terry and her husband adopted a fifth child, Joseph, an orphan whom Mary befriended when she was in Boston for medical treatment.

Her daughter’s illness and her own coming to terms with Mary’s condition formed the basis for Terry’s first book, Courage! (1938). The book was written under the pseudonym Mary Lindsey. Her other books include Cordelia, Member of the Household (1967), about a young African American girl who lived with the Fletcher family when Terry was a child; Charlotte Stephens, Little Rock’s First Black Teacher (1973), a biography of Charlotte Stephens; and her unpublished autobiography, Life is My Song, Also (1973–1974).

While her husband served in the army during World War I, Terry continued to put her energy behind social and political causes. Shortly after the war, she was one of three white women to act as an adviser to the newly established black Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA). While her sister Mary was a leading local suffragette, Terry also marched for voting rights for women in 1920. “To me, the vote represents more than just saying how a person feels about an issue or a candidate,” she said. “It represents human dignity and the fact that a citizen can express his or her opinion on any subject without fear of reprisal. That, I think, is what real human dignity consists of.”

Terry’s husband served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1933 to 1942. During her husband’s early years in Washington DC, Terry remained in Little Rock to raise their children and head an American Legion auxiliary committee that secured federal funds to pay the salaries of librarians in Arkansas. As part of that arrangement, she and the committee collected books and found the space to open free libraries throughout the state. The committee also convinced the Arkansas legislature to create a state library program. In Little Rock, Terry was a trustee of the city public library for about forty years, retiring in 1966. She recalled, in an interview a few years before her death, that she worked quietly to open the library to black adults in the 1950s and then to black children.

Also in the 1930s, Terry and others formed the Little Rock Housing Association to secure federal funds under the 1937 Housing Authority Act to combat slum housing. She later organized a group of women who spoke on radio programs and before civic groups about the importance of low-rent housing and slum clearance. During this time, she was also active in the Arkansas chapter of the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching.

In the fall of 1957, when Terry learned that Governor Orval Faubus had used troops to prevent black students from attending Central High School during the Little Rock desegregation crisis and that a white mob had terrorized the students, she wrote: “For days, I walked about unable to concentrate on anything, except the fact that we had been disgraced by a group of poor whites and a portion of the lunatic fringe…. Where had the better class been while this was being concocted? Shame on us.”

Terry and two friends, Vivion Brewer of Scott (Pulaski and Lonoke Counties) and Velma Powell of Little Rock, formed the Women’s Emergency Committee (WEC) after a ballot measure to close Little Rock’s high schools, as a means of avoiding desegregation, passed in 1958. They became the first organized group of white moderates to oppose the governor and demand the reopening of the city’s four public high schools which had been closed.

In the months following its formation, the WEC worked to persuade the public to reopen the schools. In May 1959, the WEC, black voters, and a group called Stop This Outrageous Purge campaigned successfully to recall three school board members who were segregationists. The recall election was the first full-scale loss for Faubus and the segregationists. The WEC efforts, including a study documenting the negative effect the school crisis was having on Little Rock’s economy, altered the course of public action and helped reopen the schools in 1959.

In other efforts, Terry was instrumental in starting the Pulaski County Tuberculosis Association and the Community Chest, the forerunner of the United Way. She was active in historic preservation and the arts. In later years, she worked to make the city auditorium accessible to older people and the handicapped.

Terry had a stroke sometime after her ninetieth birthday, and her health declined. Her family moved her to a nursing home from the antebellum mansion the Pike-Fletcher-Terry House, which was built by Albert Pike, where she had lived since she was a child. She died on July 25, 1976, in the nursing home at age ninety-three. She is buried in Mount Holly Cemetery in Little Rock.

Terry and her sister, Mary Fletcher Drennan, willed the family mansion to the city of Little Rock, and it became the Decorative Arts Museum of the Arkansas Arts Center (now the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts). In the fall of 2004, the former Decorative Arts Museum was renamed the Arkansas Arts Center Terry House Community Gallery and reopened as a space for collaborative exhibitions and programs with arts and non-profit agencies, although this was later closed. The Adolphine Fletcher Terry Library of the Central Arkansas Library System is named for her. In 2023, she was inducted into the Arkansas Women’s Hall of Fame.

For additional information:

Bayless, Stephanie. Obliged to Help: Adolphine Fletcher Terry and the Progressive South. Little Rock: Butler Center Books, 2011.

Cahill, Bernadette. “Stepping outside the Bounds of Convention: Adolphine Fletcher Terry and Radical Suffragism in Little Rock, 1911–1920.”Pulaski County Historical Review 60 (Winter 2012): 122–129.

Fletcher-Terry Papers. Center for Arkansas History and Culture. University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, Arkansas.

Fraley, Dianna Owens. “Adolphine Fletcher Terry (1882–1976): Seventy-Five Years of Social Activism in Arkansas.” In Arkansas Women: Their Lives and Times, edited by Cherisse Jones-Branch and Gary T. Edwards. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2018.

———. “The Conscience of Arkansas: The Progressive Reform Efforts of Adolphine Fletcher Terry, 1902–1976.” PhD diss., University of Memphis, 2017. Online at https://digitalcommons.memphis.edu/etd/1683/ (accessed June 21, 2022).

Lindsey, Mary. Courage!. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1938.

Murphy, Sara Alderman. Breaking the Silence: Little Rock Women’s Emergency Committee to Open Our Schools, 1958–1963. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1997.

Terry, Adolphine Fletcher. Cordelia, A Member of the Household. Fort Smith, AR: South and West, Inc., 1967.

Peggy Harris

Little Rock, Arkansas

This entry, originally published in Arkansas Biography: A Collection of Notable Lives, appears in the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas in an altered form. Arkansas Biography is available from the University of Arkansas Press.

Civil Rights and Social Change

Civil Rights and Social Change World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967

World War II through the Faubus Era, 1941 through 1967 Adolphine Krause Fletcher

Adolphine Krause Fletcher  Terry Library

Terry Library  Adolphine Fletcher Terry

Adolphine Fletcher Terry  Adolphine Fletcher Terry

Adolphine Fletcher Terry  Adolphine Fletcher Terry

Adolphine Fletcher Terry  Adolphine Fletcher Terry

Adolphine Fletcher Terry  Adolphine Fletcher Terry

Adolphine Fletcher Terry  Adolphine Fletcher Terry

Adolphine Fletcher Terry  Mary Fletcher Terry

Mary Fletcher Terry  Mary Fletcher Terry

Mary Fletcher Terry  WEC Members Brewer, Terry, and House

WEC Members Brewer, Terry, and House

Comments

No comments on this entry yet.