calsfoundation@cals.org

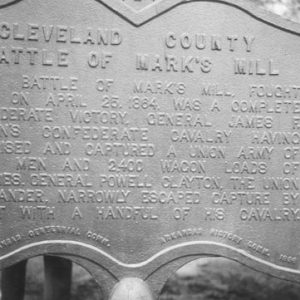

Action at Marks' Mills

| Location: | Cleveland County |

| Campaign: | Camden Expedition |

| Date: | April 25, 1864 |

| Principal Commanders: | Lieutenant Colonel Francis Drake (US); Brigadier General James F. Fagan (CS) |

| Forces Engaged: | William E. McLean’s Brigade, Second Missouri Light Artillery Battery E, and additional elements (US); Brigadier General Joe Shelby and Brigadier General William L. Cabell’s division (CS) |

| Estimated Casualties: | 1,500 estimated (US); 293 (CS) |

| Result: | Confederate victory |

The Action at Marks’ Mills took place on April 25, 1864, when Confederate troops ambushed a Union supply train, capturing all the wagons and artillery and most of the troops. Confederate soldiers were accused of massacring African Americans at this battle.

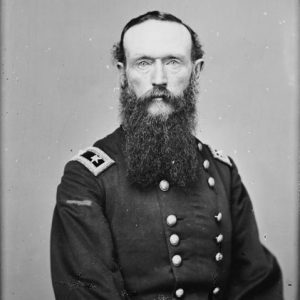

After the April 18 defeat at the Engagement at Poison Spring, Union forces under the command of Major General Frederick Steele continued to hold Camden (Ouachita County) while Confederate Major General Sterling Price maintained pressure on Steele from the countryside. With supplies dwindling, the acquisition of rations became important to the Union troops. The arrival of provisions from Pine Bluff (Jefferson County) on April 20 convinced Steele that more materials could be obtained there. Three days later, he dispatched Lieutenant Colonel Francis Drake with more than 1,200 infantrymen, several pieces of artillery, and cavalry support with 240 wagons to obtain supplies at Pine Bluff. An unknown number of white civilians and 300 black civilians accompanied the Union force to safety. On the morning of April 25, 150 cavalrymen from Pine Bluff met Drake, increasing the Union column to nearly 1,800 combatants, with 520 troops trailing the column at some distance.

Learning of Drake’s departure from Camden, Confederate Brigadier General James F. Fagan positioned his more than 2,000 cavalrymen near the juncture of the Camden-Pine Bluff Road with the Warren Road, cutting off Drake’s route. Setting an ambush, Fagan ordered Brigadier General Joe Shelby’s division to the east on the Camden-Pine Bluff Road to block possible escape toward Pine Bluff, and Brigadier General William L. Cabell’s division was to attack from the southwest. Early on April 25, Cabell’s division began a poorly planned piecemeal attack on Drake’s column. Sending one brigade into combat before the second was positioned, Cabell’s troops won the wagons but exposed themselves to intense counterfire. The Forty-third Indiana and the Thirty-sixth Iowa regiments took advantage of this error and slowed the Confederate attack until Union reinforcements helped stop his advance. Cabell’s division lost its momentum and found it difficult to regain it. Nonetheless, the Union units slowly began to lose control of the battle because of the overwhelming Confederate numbers.

Shelby, attacking from the east, hammered the unsuspecting Union left. Caught off guard and with Drake seriously wounded, the Union troops capitulated after nearly five hours of engagement. Hearing the sounds of battle in front of them, 500 men from the First Iowa Cavalry, on furlough and trailing at a distance, sped forward to help by engaging the enemy to the west of Marks’ Mills. The First Iowa eventually broke off its attack to escape the large Confederate numbers. Cabell’s command suffered 293 casualties (41 killed, 108 wounded, 144 missing), while Union casualty estimates range from 1,133 to 1,600, with most being captured and an estimated 100 killed. The Confederates captured about 150 black freedmen and are believed to have killed more than 100 others.

The defeat of Drake’s command had a significant impact upon Steele’s position at Camden. Coupled with the defeat at Poison Spring, the loss at Marks’ Mills prevented Steele from obtaining much-needed supplies for his army. Already on reduced rations and with reports of Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith’s command marching northward from Louisiana, Steele’s position became untenable. With all possibility of supporting Banks’s campaign on the Red River gone, the Union army silently slipped over the Ouachita River on the night of April 26, abandoning Camden and beginning a desperate race back to Little Rock (Pulaski County), which resulted in the Engagement at Jenkins’ Ferry. Furthermore, the killings of the black soldiers at Poison Spring, paired with the large number of black freedmen killed at the Action at Marks’ Mills, enraged many in the Union army. As a result, the First Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment exacted revenge upon Confederate combatants and wounded at the Engagement at Jenkins’ Ferry, amplifying the legacy of racial atrocities in the Camden Expedition.

Marks’ Mills Battleground State Park preserves a small segment of the battlefield near New Edinburg (Cleveland County). Edgar Colvin and Sue Marks Colvin additionally present interpretative materials and monuments to the battle and the Marks family homestead at the Marks Cemetery and Marks’ Mills Historic Battlefield Site north of the state park off Highway 97 in Cleveland County.

For additional information:

Baker, William D. The Camden Expedition of 1864. Little Rock: Arkansas Historic Preservation Program, 1993.

Bearss, Edwin C. Steele’s Retreat from Camden and the Battle of Jenkins’ Ferry. Little Rock: Arkansas Civil War Centennial Commission, 1967.

Broeg, Cormac. “The Massacre at Marks’s Mills: How Confederates Murdered ‘Near 30’ Black Refugees and Reenslaved 150 Others.” Civil War History 71 (March 2025): 11–41.

Christ, Mark K. “‘He Died Right Away’: A Black Woman’s Account of Murder at Marks’ Mills.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 83 (Spring/Summer 2024): 77–86.

Christ, Mark K., ed. Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1994.

DeBlack, Tom. With Fire and Sword: Arkansas, 1861–1874. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2003.

Richards, Ira Don. “The Engagement at Marks’ Mills.” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 19 (Spring 1960): 51–60.

Urwin, Gregory J. W. “We Cannot Treat Negroes…as Prisoners of War: Racial Atrocities and Reprisals in Civil War Arkansas.” Civil War History 42 (September 1996): 193–210.

Derek Allen Clements

Pocahontas, Arkansas

My second great-granduncle Samuel Amon Lee was captured at Marks’ Mills. He was a private in Co. K in the 77th Ohio. He spent time at Camp Ford as a POW.

My great-great-grandfather, Sergeant Michael Hittle, served in Company A of the Thirty-sixth Iowa Infantry and was in the battle at Marks Mills. In 1878, his accounts were published in The History of Monona County, Iowa. He was taken prisoner at Marks Mills, but he and twenty-one others managed to escape. Heading back down the CamdenPine Bluff Road, they ran into an officer of the 77th Ohio and warned him of the overwhelming enemy ahead. The officer did not heed their warning, accusing them of being deserters.

Unarmed and out of food and water, they struck out through the bush to reach Federal lines. Hittle recounted that he made it back to Little Rock, but he also said that he fought at Jenkins Ferry. I conclude from this that he was likely one of the wild eyed stragglers from the Marks Mills battle who found General Steeles army encamped at Princeton on April 28 on its move north toward the Saline.

Hittles father, Corporal Jacob Hittle of the same companyand regiment, had been left sick in quarters at Camden when the Thirty-sixth was assigned to escort the wagon train back to Pine Bluff on April 23. I conclude that Hittle and his father had a happy reunion at Princeton around April 28.

According to Ed Bearsss Steeles Retreat From Camden and the Battle of Jenkins Ferry (1961), the surviving members of the Thirty-sixth Iowa, 43rd Indiana and 77th Ohio were assigned to a Provisional Detachment under Captain Marmaduke Darnall (43rd Indiana), and played a prominent role in providing enfilading fire support to the famous charge of the 2nd Kansas Colored Infantry of the Confederate center at Jenkins Ferry. Happily, both Sergeant Hittle and Corporal Hittle survived the war.

I have the memoirs of Captain Seth Swiggett, Commanding Officer of Company B, Thirty-Sixth Iowa, published in 1897. Swiggetts account of the events leading up to the ambush differs significantly from the dispatches in the Official Record (Vol. XXXIV) of Lieutenant Colonel F. M. Drakeand from every account of the battle I have ever read. It is documented that General Steele ordered Drake not to attempt a crossing of the Moro bottom in the evening. However, Drake reported after the battle that he stopped the train on the west bank of the Moro on Sunday evening, April 24th. According to Swiggett, the civilian teamsters were getting out of hand, complaining to Drake about the rapid pace on Sunday. Drake halted the train and went into bivouac on the west bank at 2:00 p.m., not in the evening. The pioneer corps was sent forward to try to make improvements to the soggy bottom road leading to the bridge crossing, but as Swiggett recounted, a feeling of foreboding descended on them that Sunday afternoon. Swiggett contended that had Drake not acquiesced to the civilian teamsters and halted the train at 2:00 p.m., the train could have made its crossing well before nightfall, gaining several miles toward Pine Bluff before that fateful Monday morning. Obviously, Swiggetts account alters the widely accepted narrative about the timing of Drakes order. Thus, what transpired at Marks Mills should never have happened. Moreover, Swiggetts narrative calls Drakes official report into serious question. As we also know, Rebel General Fagan was nonplussed to learn from his scouts that Drake had halted where and when he did. Drakes decision gave Fagan more than ample time to slip ahead and set up the ambush plan at the Marks plantation.