calsfoundation@cals.org

Tree of Talking: What Makes an Arkansan?

In his 1998 book The User Illusion: Cutting Consciousness down to Size, Danish science writer Tor Nørretranders introduces the concept of a “tree of talking.” The idea is that if I want to communicate something to you, I have to take my disparate ideas and images and distill those into a narrower term or phrase, and if you were to graph that out, it would appear like a tree going from top to bottom, as all the twigs lead into branches and the branches into a trunk. That concept, once delivered, expands in your head with its own series of associations and relations that may not always accord with mine.

For example, if I wanted to convey to you a relationship I had with an older mentor, I might sift through the ideas I want to convey, how someone can be both stern and nurturing, and eventually arrive at the trunk of the phrase: “He was like a father to me.” When I say such a word, I hope that the image unravels in your head to produce the same branching set of associations that I worked to condense down. Your own father, however, may have been absent or abusive, and so your own personal experience isn’t the same as mine, but this doesn’t mean we necessarily misunderstand each other, for the images and narratives you have imbibed from the culture at large may instill an understanding of what I am trying to communicate.

For example, if I wanted to convey to you a relationship I had with an older mentor, I might sift through the ideas I want to convey, how someone can be both stern and nurturing, and eventually arrive at the trunk of the phrase: “He was like a father to me.” When I say such a word, I hope that the image unravels in your head to produce the same branching set of associations that I worked to condense down. Your own father, however, may have been absent or abusive, and so your own personal experience isn’t the same as mine, but this doesn’t mean we necessarily misunderstand each other, for the images and narratives you have imbibed from the culture at large may instill an understanding of what I am trying to communicate.

Our shared sense of references constitutes our “tree of talking.” Sometimes, that set of references is exclusive to a small group of friends—the inside jokes that eventually get reduced to a few shorthand words, because that’s all that’s needed to unfurl the whole thing in your mind. Sometimes, the set of references is local, with everyone in town knowing just what year you mean when you say, “The year the tornado came through.” Sometimes, the set of references is specific to a particular culture or subculture; certain churches may draw from the same source material and share some of the same doctrines, but a Southern Baptist wandering into a Roman Catholic mass without proper preparation will find himself just a bit lost. And then there are sets of references that, we like to imagine, draw from the shared culture of all humankind, with Shakespeare’s “To be or not to be” constituting perhaps the most recognizable line in all of literature.

When we aim for the broadest impact, we draw a tree of talking that we believe will resonate with the most readers or listeners. It’s why politicians and activists constantly exclaim, “This is just like 1984!” Most Americans read George Orwell’s 1984 in high school, and although most probably don’t remember the nuances of the novel, 1984 serves as a good shorthand—say that number, and the tree starts to branch out with images of oppression and constant government surveillance and the like.

Like any tree, our trees of talking occasionally drop a branch, occasionally grow a new one, as our relationships and our cultures evolve. An inside joke among friends may cease to have resonance and thus cease to be mentioned for a while, until one day those on the inside of that joke might remember the key word that once triggered so much laughter but not quite remember why it was funny. Or a new television show or movie or book becomes the thing that everyone is currently imbibing, providing new a shorthand for certain ideas or concepts or stories. Part of the reason that there is such a market for books like Star Trek and Philosophy or Harry Potter and Philosophy is that philosophy has often approached issues of ethics or essence through stories.

Trees of talking exist at all levels, from the private language of couples to the canons of literature. The smoothness of our communication and coordination with other people depends upon engaging the appropriate framework for shared understanding.

However, in our current world, those trees of talking that tend to be most starved of attention lie in the mid-range between the local and the national. Unless you are a desert hermit or live off the grid and away from people, there is some local community of which you are a part, and even if your participation in the life of the community is minimal, there are still certain events that will form part of the local tree of talking, such as tornadoes or house fires. That’s one end of the spectrum. At the other, we have the national framework that has often come to dominate the conversation, so that even state and local elections now center upon national issues that often have no bearing on the position being sought.

But what about the state level? States are strange things, agglomerations of different regions located within a specific set of boundaries for reasons often contentious and sometimes arcane. Arkansas, for example, includes such varying geographical regions as the Delta flatland in the east and the Ozark and Ouachita hills in the north and west. And these are different cultures.

I grew up in eastern Arkansas, on Crowley’s Ridge, and became rather obsessed with hills and mountains as the opposite of all that Delta flatness that surrounded us. I once asked my grandmother, who grew up in and lived in Parkin, whether she might ever consider moving to a place with “real geography.” She said, “No, never. I like being able to see what my neighbors are doing.” The Delta is like Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, where everyone can observe you, whereas the hills are where you move to get away from prying eyes. It’s why the Ozarks have been home to everything from left-wing lesbian communes to right-wing militias and cults. Just depends upon what set of eyes you are trying to escape.

So how does drawing a line around and through these clusters of geography make for something like a state and give the people in that state any sense of shared identity? Does state identity track toward something like national identity? In some respect, we can see this at work, especially in those places where state identity assumes a rather nationalistic form (e.g., Texas). But in other ways, the notion doesn’t quite fly. We typically find moving to another state less psychologically challenging (and less exciting) than moving to another country. While I’ve had friends move from a bigger Arkansas town to a smaller Arkansas town and still years later hear themselves described as being “from off,” the reverse journey is not so exclusionary, as cities are always home to plenty of people “from off” who moved there for work or opportunity.

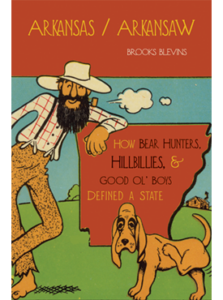

What, then, makes for state identity? Here, we need to make an important distinction, for image is not the same as identity. One’s image constitutes how one is seen from another’s perspective. I remember once, when I was young, watching Murder, She Wrote and being shocked at Jessica Fletcher using the term “Yankee hospitality,” for we knew that the South was the source and summit of hospitality, while “Yankee” was synonymous with brash, rude, arrogant, and motormouthed. That’s not the way these Yankees saw themselves, however, and neither do most Arkansans regard themselves as backwoods, inbred, violent, and uneducated. But sometimes, one can develop an identity around opposition to an entry, and Arkansas stands out here. As Brooks Blevins writes in his 2009 book, Arkansas/Arkansaw: How Bear Hunters, Hillbillies, & Good Ol’ Boys Defined a State, “the defenders of Arkansas’s honor are without a doubt the funniest characters in this saga, and the vociferousness with which they have given voice to that collective inferiority complex has served as a catalyst for further stereotyping. Arkansans’ defensive reactions to their state’s genuine image problems have had the effect of water on a grease fire, intensifying rather than subduing the stereotyping.”

What, then, makes for state identity? Here, we need to make an important distinction, for image is not the same as identity. One’s image constitutes how one is seen from another’s perspective. I remember once, when I was young, watching Murder, She Wrote and being shocked at Jessica Fletcher using the term “Yankee hospitality,” for we knew that the South was the source and summit of hospitality, while “Yankee” was synonymous with brash, rude, arrogant, and motormouthed. That’s not the way these Yankees saw themselves, however, and neither do most Arkansans regard themselves as backwoods, inbred, violent, and uneducated. But sometimes, one can develop an identity around opposition to an entry, and Arkansas stands out here. As Brooks Blevins writes in his 2009 book, Arkansas/Arkansaw: How Bear Hunters, Hillbillies, & Good Ol’ Boys Defined a State, “the defenders of Arkansas’s honor are without a doubt the funniest characters in this saga, and the vociferousness with which they have given voice to that collective inferiority complex has served as a catalyst for further stereotyping. Arkansans’ defensive reactions to their state’s genuine image problems have had the effect of water on a grease fire, intensifying rather than subduing the stereotyping.”

Is that enough to make an Arkansas identity—simple opposition to its image? But there are plenty who have embraced the image in the full spirit of contrarianism. Hell, I certainly have. When my Swedish friend Henrik came to visit me for a week in the early 2000s, I took him to Blanchard Springs Caverns, plied him with some muscadine wine afterward, and then some friends got us a few four-wheelers that we drove up and down some old logging trails with a case of Busch beer in tow. Henrik had stopped over after doing some physics research at UC Berkeley, and I just wanted him to have an American experience he probably couldn’t have on the urban West Coast. But in the evening, we drove back to Jonesboro and went to The Edge coffeehouse right off the Arkansas State University campus, then run by my friend Ann Williams, where we ate a delicious Middle Eastern meal (I still remember the dolma) prepared by a guest chef. Was that any less a “true” Arkansas experience than our earlier four-wheeler expedition?

What makes an Arkansan? On what tree of talking are we all roosting? Defending “Arkansas’s honor” can, in one moment, lead to an embrace of the image, and the next a rejection—all depending upon who is impugning said honor. In this way, maybe, Arkansas’s identity is a little bit evanescent, like a subatomic particle whose direction cannot be inferred until it is observed by someone.

If nothing else, we can all agree that the phrase “Yankee hospitality” just sounds strange, doesn’t it?

By Guy Lancaster, editor of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas