calsfoundation@cals.org

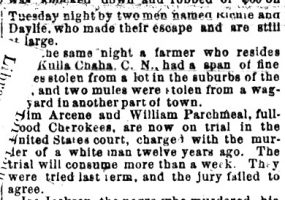

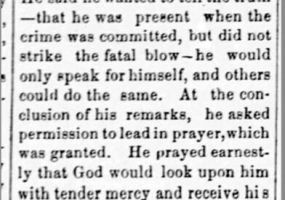

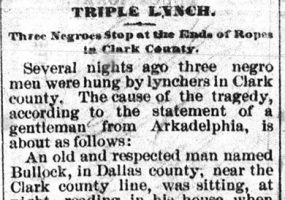

1875 - 1900

Post-Reconstruction through the Gilded Age

aka: State Woman's Suffragist Association

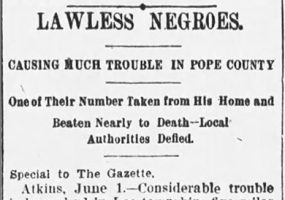

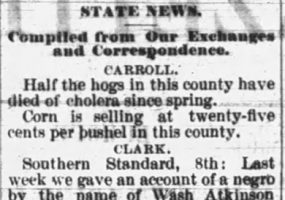

aka: Sam Jackson (Lynching of)