calsfoundation@cals.org

Elaine Massacre of 1919: Legacy of Race in Arkansas

Objective(s)

Students will engage secondary sources in order to understand and participate in the creation of historical narrative.

Key Vocabulary

- Primary Sources: first-hand information from those who experienced a time or event. Includes memoirs, interviews, letters, and public documents.

- Secondary Sources: second-hand information; works that have been collected, interpreted, or published by someone other than the original source

- World War I: also called the Great War; global conflict from 1914 to 1918 between the Allies and Central Powers. It marked the first true modern war and demonstrated unprecedented levels of death and destruction.

- Sharecroppers: when slavery was abolished, many white landowners were without field workers. They made contracts (often unfair) with many poor and Black Americans, allotting a plot of land from the landowner’s property for them to live on and work, and in exchange they were required to sell their crops back to the landowners for them to profit.

- Insurrection: a violent uprising against an authority or government

- Lynching: the killing of someone, especially by hanging, for an alleged offense without trial, often by mob violence

- “The Arkansas Race Riot”: a 1920 informational pamphlet that provides critical information about the Elaine Massacre of 1919; written by famous anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett

Necessary Materials

Pen or pencil, lined paper, internet access (if available), printed related EOA entries (if needed)

Historical Background

The Elaine Massacre was by far the deadliest racial confrontation in Arkansas history and possibly the bloodiest racial conflict in the history of the United States.

Despite cotton being incredibly profitable at the time, Black sharecroppers working under white landowners were being paid pennies on the dollar. So, on September 30, 1919, a union meeting for the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America was held at a church in Hoop Spur, three miles north of Elaine (Phillips County). The goal of this union meeting was to determine how to secure market price for their cotton, rather than the discounted prices they were being paid. The union contacted lawyer Ulysses S. Bratton to represent them in potential negotiations with the white landowners; Bratton sent his son Ocier to attend the meeting.

Meanwhile, racial conflict had been occurring in various cities throughout America. With the end of World War I, Black soldiers returned to a staunchly segregated Jim Crow society with a far less submissive attitude. The presence of headstrong Black Americans and the growing Red Scare at the time made a union like the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America ripe for fearmongering.

During the meeting, to prevent disruption, armed guards were placed outside. Who shot first is in contention, but nonetheless, a shootout between these guards and a vehicle parked in front of the church resulted in the death of W. A. Adkins, a white security officer for the Missouri Pacific Railroad, and the wounding of Charles Pratt, Phillips County’s white deputy sheriff.

The next morning, the Phillips County sheriff sent out a posse to arrest those involved in the shooting. Despite minimal resistance from Black residents in the area, the group of armed white individuals labeled the shootout as the start of an insurrection. Thus, upon arriving, the armed white mob began to fire upon those Black residents of Elaine. The killing was indiscriminate.

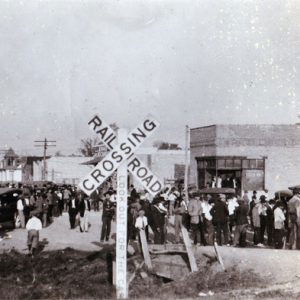

On October 1, authorities requested the governor send U.S. troops to Elaine. He promptly sent 500 combat-ready troops to the small town. On October 2, the white mob returned to their homes and the military questioned several hundred Black residents about the events. Though the military documented only two Black Americans dead, Memphis Press correspondents wrote that many more were killed. Some anecdotal evidence even points to the U.S. troops engaging in torture to get confessions out of Black Elaine residents.

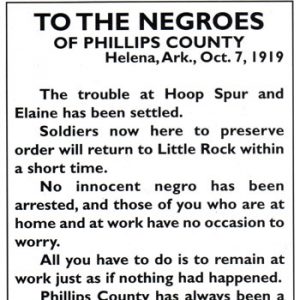

Two narratives exist past this point. One, from white leaders, describes the union activity as a Black insurrection that was promptly and adequately put down. They even described the union as being established for the purpose of banding together for the killing of white people, something it explicitly was not intended to do. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), however, labeled the claims of an insurrection as “only a figment of the imagination of Arkansas whites and not based on fact.” The pamphlet “The Arkansas Race Riot” documented the other side of the narrative, including the deaths and torture of those held for questioning.

Evidence shows without question that the mob and military killed many Black individuals in the area, something not unheard of given past militia activity as well as the history of lynching at the time. By the end of the conflict, 285 Black citizens were wrongfully imprisoned, 122 were charged for crimes stemming from racial disturbances, and twelve were sentenced to death by electric chair. Those twelve were the first to stand trial, and were promptly named the Elaine Twelve, becoming a subject for activism; eventually all twelve were released. One of the cases on behalf of the Elaine Twelve, Moore v. Dempsey, expanded the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to allow state rulings to be challenged in federal courts to ensure defendants were properly given their federal constitutional rights.

Activities

Bellringer

Ask students to write down their answers to the following questions before opening the floor for class discussion:

How do you think public opinion on the rights of Black Americans changed after the Civil War? Did it become more favorable toward African Americans and their rights, did it reflect the idea that Black citizens should not have the same rights as whites, or did it stay the same as it had been before the war and the end of slavery?

What new opportunities were available to Black citizens after the Civil War? Elaborate on your answers.

After students have written their answers, ask around the room to hear what some students had to say. For question 2, allow students to list new opportunities aloud and write down these opportunities on the board as they do so. For question number 1, if students:

- Answered “more favorable,” inquire how exactly. Support students’ answer with historical context, things like job opportunities, the Great Migration, the abolitionist movement, etc.

- Answered “Blacks should not have equal rights,” inquire how exactly. Support students’ answer with historical context, such as Jim Crow laws, sharecropping, lynchings, etc.

- Answered “stayed the same,” challenge students to explain how things could stay the same after such a significant system as slavery ended? Utilize this to transition into an explanation or discussion about sharecropping.

Direct Instruction

The teacher will deliver direct instruction to students; students will take focused notes during this. Make sure by the end of direct instruction students know:

- The relevant historical context, including: what is sharecropping, review of World War 1 and how Black Americans participated in the fighting, what was the Red Scare, and any other relevant details determined by the teacher

- How tensions between the sharecroppers and the landowners came to be and why they were particularly high at this time

- The historical prevalence of the fear of Black insurrectionism

- The two narratives: one from Black residents of Elaine and one from the white leaders

- The Elaine Twelve and the legal system

Engaging Secondary Sources

Students will read two entries from the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas via printouts or digital access.

First, they will read the entry titled Elaine Massacre of 1919. As they read, students should utilize marking the text strategies as well as answer the following questions in preparation for class discussion:

- What narrative do white members of the Elaine community hold over one hundred years after the Elaine Massacre? Explain their perspective in detail.

- How did this narrative come to exist originally?

Next, students will read the EOA entry titled The Arkansas Race Riot, which summarizes the contents and context of the 1920 pamphlet by Ida B. Wells-Barnett. (The full pamphlet of “The Arkansas Race Riot” can be accessed here: https://archive.org/details/TheArkansasRaceRiot) As students read, they should utilize marking the text strategies as well as answer the following questions in preparation for class discussion:

- What narrative does this pamphlet propose regarding the events of the Elaine Massacre?

- Given what you have learned about Arkansas at this time, does this pamphlet present a narrative that seems detailed and believable?

Class Discussion

As the EOA entry notes, following the massacre, there were two narratives of the event that entered circulation. One, promoted by local elites and state authorities, held that local African Americans were engaged in an “insurrection” with plans to kill all the whites in the county. The other dominant narrative held that Black sharecroppers were organizing a union with the hopes of receiving better pay for their labor.

As the teacher, lead a discussion on the credibility of these two narratives. Possibilities for discussion might include:

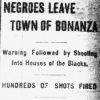

- Which sources promulgated which specific narratives. That is, look at how white-owned newspapers covered the event versus how writers like Ida B. Wells-Barnett portrayed it.

- The motivations underlying each narrative. Why might plantation owners, for example, spread tales of an “insurrection”?

- The likelihood that any supposed “insurrection” could achieve success in eastern Arkansas at the time. Would Black sharecroppers have actually believed that they could overthrow local elites without any kind of repercussions?

- The work of Ida B. Wells-Barnett. The teacher might read a selection from “The Arkansas Race Riot” and ask students whether it presents the sort of detail that makes it a believable source. Too, what does some of the previous research conducted by Wells-Barnett reveal about her character?

By the end of discussion, students should understand how historical sources themselves craft narratives, and they will come to see that this is not necessarily a bad thing. Narratives are the human method of relating history, and understanding where those narratives come from and why is the best way we can understand each other, understand our past, and continue toward progress in the future.

Why we trust the narratives we do is a skill that must be learned. That is what lessons like this one are for, teaching students to understand what to trust and why to trust it.

Evaluation

Student evaluations are based on student responses to reading questions, but primarily are founded on class discussion. Students should be graded based on participation, unique and robust responses, and cooperation with classmates.

Awaiting Arrival of Troops at Elaine Depot

Awaiting Arrival of Troops at Elaine Depot  Elaine Machine Gun Emplacement

Elaine Machine Gun Emplacement  Elaine Temporary Stockade

Elaine Temporary Stockade  Elaine Massacre Flyer

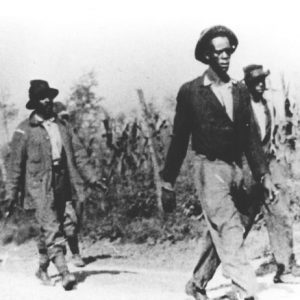

Elaine Massacre Flyer  Elaine Massacre Prisoners

Elaine Massacre Prisoners  Red Cross Canteen at Elaine

Red Cross Canteen at Elaine

"*" indicates required fields