calsfoundation@cals.org

Illuminating History Outside the Headlines

I’ve been contemplating the nature of history recently, as we often do here at the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas. I’m sure that this is not a great surprise to readers of this blog.

This contemplation stems, in part, from listening to an audiobook of Pulitzer Prize-winning author Barbara W. Tuchman’s 1978 book, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. She begins the book by listing the various sources we have for late medieval history, commenting on how they can easily skew our perception of the time period, especially given, as she notes, that no pope ever issued a papal bull for something of which he approved, but rather almost exclusively against something. Building upon this, she writes:

This contemplation stems, in part, from listening to an audiobook of Pulitzer Prize-winning author Barbara W. Tuchman’s 1978 book, A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. She begins the book by listing the various sources we have for late medieval history, commenting on how they can easily skew our perception of the time period, especially given, as she notes, that no pope ever issued a papal bull for something of which he approved, but rather almost exclusively against something. Building upon this, she writes:

Disaster is rarely as pervasive as it seems from recorded accounts. The fact of being on the record makes it appear continuous and ubiquitous whereas it is more likely to have been sporadic both in time and place. Besides, persistence of the normal is usually greater than the effect of the disturbance, as we know from our own times. After absorbing the news of today, one expects to face a world consisting entirely of strikes, crimes, power failures, broken water mains, stalled trains, school shutdowns, muggers, drug addicts, neo-Nazis, and rapists. The fact is that one can come home in the evening—on a lucky day—without having encountered more than one or two of these phenomena. This has led me to formulate Tuchman’s Law, as follows: “The fact of being reported multiplies the apparent extent of any deplorable development by five- to tenfold” (or any figure the reader would care to supply).

It’s been noted by psychologists that we tend to remember much more readily and much more deeply the insults and injuries to which we have been subject than we do the good things that have happened to us. Suspicion for this development typically falls upon evolution, with natural selection having engineered us to remember the bad things for the purpose of aiding us in avoidance of those things, so that we might at least live long enough to reproduce. We personally more readily remember the evils of our personal history, and history more readily records the evils that we do to each other. It rather makes one despair for our ability to produce any proper accounting of our past at all.

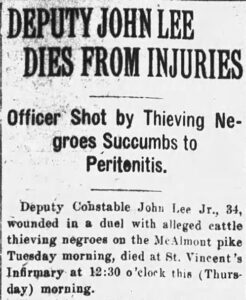

Sometimes, though, the lightning strike of violence or wrath can help to illuminate the darkness a bit and reveal some of what history typically does not record. I recently published a paper in the Spring 2023 Pulaski County Historical Review on the so-called “riots” in Brushy Island in northern Pulaski County in the late 1910s. As noted in the article and in the EOA entry on the subject, these were not so much typical so-called race riots as they were an ongoing series of interracial feuds, and the area was popularly regarded as existing near the edge of civilization, a refuge for cattle thieves and moonshiners and arsonists. That is, the newspaper only ever really reported upon Brushy Island when there had been yet another case of violence in that murky corner of the state’s capital county.

Sometimes, though, the lightning strike of violence or wrath can help to illuminate the darkness a bit and reveal some of what history typically does not record. I recently published a paper in the Spring 2023 Pulaski County Historical Review on the so-called “riots” in Brushy Island in northern Pulaski County in the late 1910s. As noted in the article and in the EOA entry on the subject, these were not so much typical so-called race riots as they were an ongoing series of interracial feuds, and the area was popularly regarded as existing near the edge of civilization, a refuge for cattle thieves and moonshiners and arsonists. That is, the newspaper only ever really reported upon Brushy Island when there had been yet another case of violence in that murky corner of the state’s capital county.

And yet… Among the attacks upon African American life in Brushy Island were the conflagrations that consumed a Black church, a Black school, and Black-owned farmhouses. The establishment of that church, that school, and those farms by African Americans did not warrant any attention at all when they happened, but here in these acts of violence we can see hints of an independent and prosperous community.

In the reports of the ongoing calamitous state of affairs at Brushy Island are hints of Black-white intermarriage, of Black and white tenants working on the same farm, of more familiar and familial concourse than you might otherwise expect at the height of Jim Crow. Moreover, much to my own surprise as someone who has studied racial violence, the local police force arrested and named those white men suspected of anti-Black vigilantism, even after one local Black man had been accused of killing a cop during some cattle-thieving gone wrong. And this man was not lynched but was tried, convicted, and released early on good behavior.

Tuchman’s Law thus can be amended somewhat. After all, Brushy Island was only the subject of scrutiny as the result of some scandal of violence or other form of criminality, but in these flashes of lightning, we can see a rather surprising landscape, one that lies not only at the margins of Pulaski County but at the margins of our historical consciousness. History becomes a bit more complex, and the “persistence of the normal” has the capacity to surprise us. So while the horrors or disasters of the past tend to consume our attention, perhaps we should use those recorded moments to peek behind the headlines and try to see what particular norms these moments are disturbing. We may well be surprised by what we discover.

By Guy Lancaster, editor of the CALS Encyclopedia of Arkansas