Entry Type: Event

Filmore, Isaac (Execution of)

Finney v. Hutto

aka: Hutto v. Finney

First Electric Cooperative's First Power Pole

First Electric Cooperative's First Power Pole

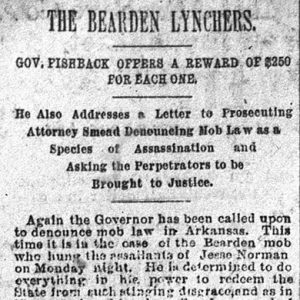

Fishback Lynchings Letter

Fishback Lynchings Letter

Fitzhugh’s Woods, Action at

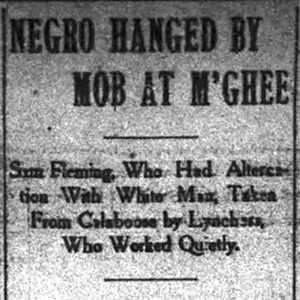

Fleming Lynching Article

Fleming Lynching Article

Fleming, Sam (Lynching of)

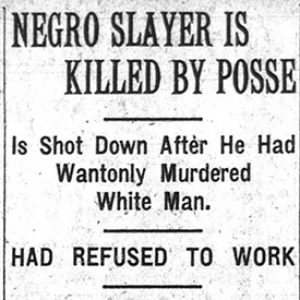

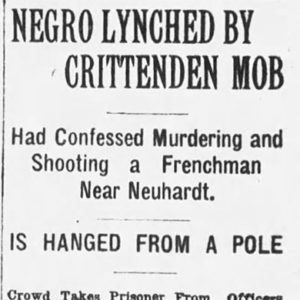

Flemming Lynching Article

Flemming Lynching Article

Flemming, Owen (Lynching of)

Flood of 1927

aka: Great Flood of 1927

aka: Mississippi River Flood of 1927

aka: 1927 Flood

Flood of 1937

Flood of 1978

Flood of 2019

Flu Epidemic of 1918

aka: Influenza Epidemic of 1918

Flynn-Doran War

Fooy, Samuel W. (Execution of)

Ford, L. L. (Execution of)

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Cake Train

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Cake Train

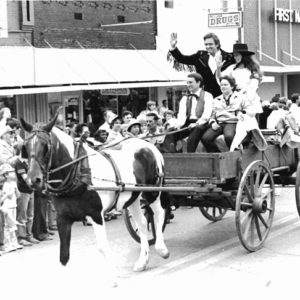

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Parade

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival Parade

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival

Fordyce on the Cotton Belt Festival

Foreman Cotton Auction

Foreman Cotton Auction

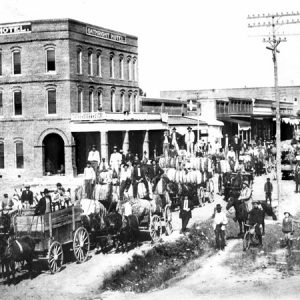

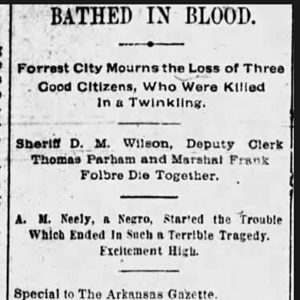

Forrest City Riot Article

Forrest City Riot Article

Forrest City Riot of 1889

Forsyth, Missouri, to Batesville, Scout from

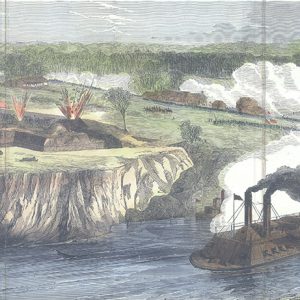

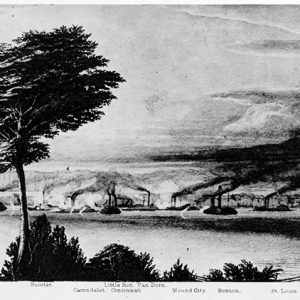

Fort Hindman Attack

Fort Hindman Attack

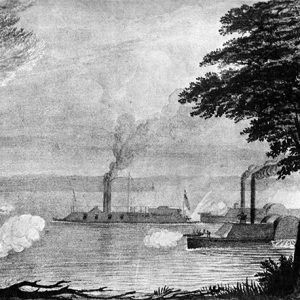

Fort Pillow, First Position

Fort Pillow, First Position

Fort Pillow, Third Position

Fort Pillow, Third Position

Fort Pinney to Kimball’s Plantation, Expedition from

Fort Smith Conference (1865)

Fort Smith Council

Fort Smith Expedition (November 5–16, 1864)

Fort Smith Expedition (November 5–23, 1864)

Fort Smith Expedition (September 25–October 13, 1864)

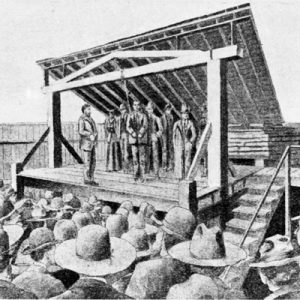

Fort Smith Hanging

Fort Smith Hanging

Fort Smith Schools, Desegregation of

Fort Smith Sedition Trial of 1988

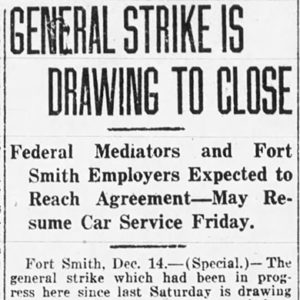

Fort Smith Strike Article

Fort Smith Strike Article

Fort Smith Telephone Operators Strike of 1917

Fort Smith Tornado of 1898

Fort Smith, Abandonment of

Fort Smith, Action at

Fort Smith, Affair at

Foster, Thomas P. (Killing of)

Bill Foster Roast

Bill Foster Roast

Warren Fox Lynching Article

Warren Fox Lynching Article