Entry Category: Law

Coronado Coal Co. v. United Mine Workers of America

aka: United Mine Workers of America v. Coronado Coal Co.

Corrothers, Helen Gladys Curl

George Corvett Lynching Article

George Corvett Lynching Article

Corvett, George (Lynching of)

Cosgrove Execution Story

Cosgrove Execution Story

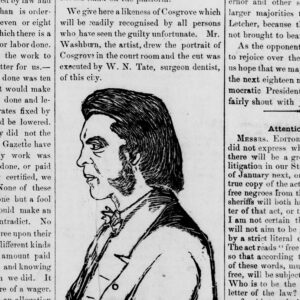

Charles Cosgrove

Charles Cosgrove

Cosgrove, Charles (Execution of)

Judge Calvin Cotham

Judge Calvin Cotham

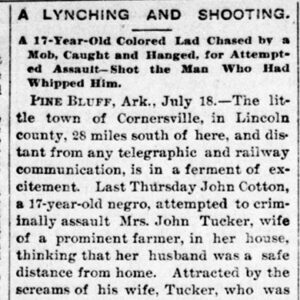

Cotton, John (Lynching of)

John Cotton Lynching Article

John Cotton Lynching Article

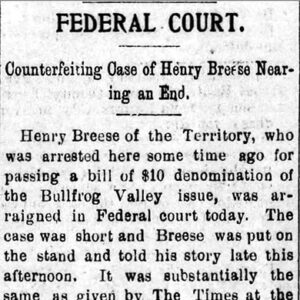

Counterfeiting Article

Counterfeiting Article

County Coroner, Office of the

County Judge, Office of

Covenant, the Sword and the Arm of the Lord

Covington, Riley (Reported Lynching of)

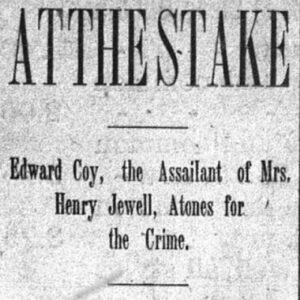

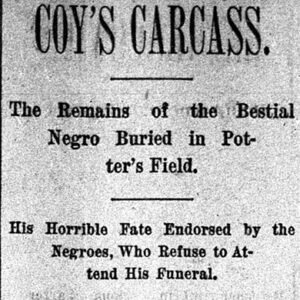

Coy, Edward (Lynching of)

Coy Lynching Article (AP)

Coy Lynching Article (AP)

Coy Lynching Article

Coy Lynching Article

Coy Lynching Article

Coy Lynching Article

Crawford County Execution Article

Crawford County Execution Article

Crawford County Execution Article

Crawford County Execution Article

Crawford County Executions of 1843

Crawford, Maud Robinson

Creed Caldwell Story

Creed Caldwell Story

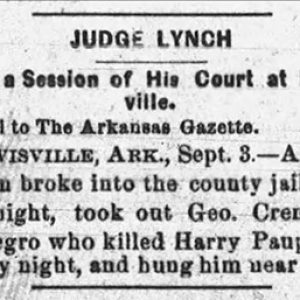

George Crenshaw Lynching Article

George Crenshaw Lynching Article

Crenshaw, George (Lynching of)

Criminal Justice Institute

Crittenden County Executions of 1871

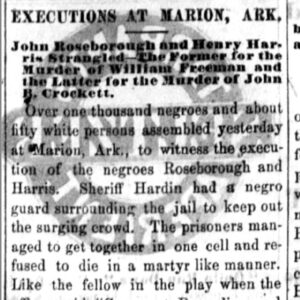

Crittenden County Executions Story

Crittenden County Executions Story

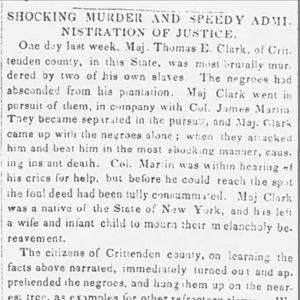

Crittenden County Lynching Article

Crittenden County Lynching Article

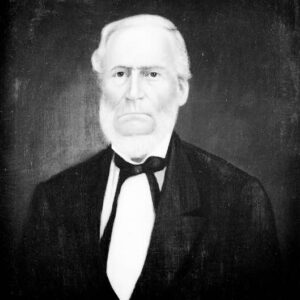

Cross, Edward

Edward Cross

Edward Cross

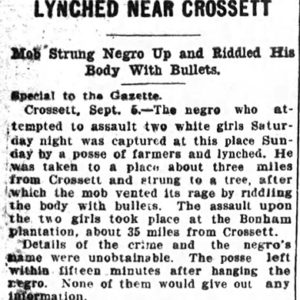

Crossett Lynching Article

Crossett Lynching Article

Crossett Lynching of 1904

Crownover (Lynching of)

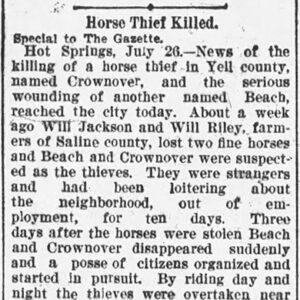

Crownover Lynching Article

Crownover Lynching Article

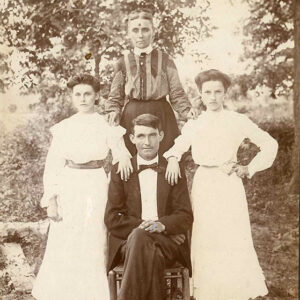

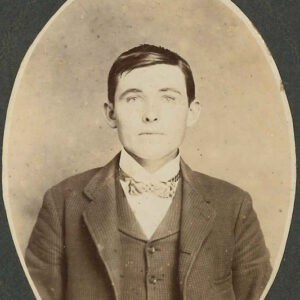

Andy Crum

Andy Crum

Andy Crum

Andy Crum

Andy Crum

Andy Crum

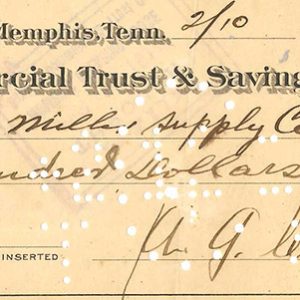

Andy Crum Bank Note

Andy Crum Bank Note

Patsy Crum at 1979-80 Constitutional Convention

Patsy Crum at 1979-80 Constitutional Convention

George J. Crump

George J. Crump

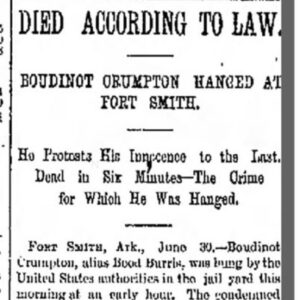

Crumpton, Boudinot (Execution of)

aka: Bood Burris (Execution of)

Crumpton, Boudinot Execution Story

Crumpton, Boudinot Execution Story

CSA Booklet

CSA Booklet