Ellison and Son

Ellison and Son

Entry Category: Law

Ellison and Son

Ellison and Son

Ellison, Clyde (Lynching of)

Ellison, Eugene (Killing of)

Eminent Domain

Emmet Lynching of 1891

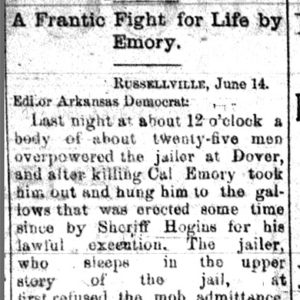

Cal Emory Lynching Article

Cal Emory Lynching Article

Emory, Cal (Lynching of)

England, Albert (Lynching of)

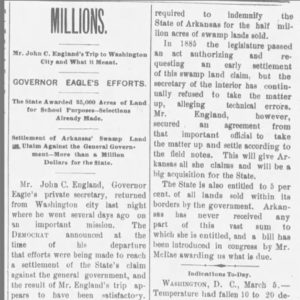

John England Article

John England Article

English, Elbert Hartwell

Enon Massacre

Epperson v. Arkansas

Susan Epperson

Susan Epperson

Susan Epperson

Susan Epperson

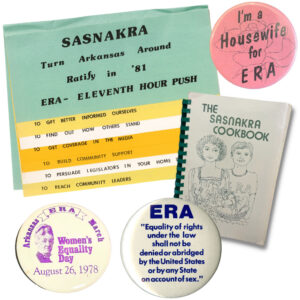

Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)

ERA Ephemera

ERA Ephemera

Erwin, Judson Landers, Jr.

Eskridge, Thomas P.

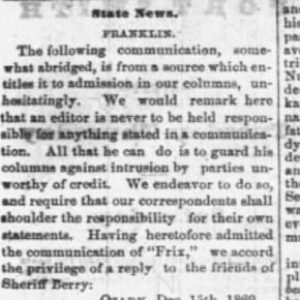

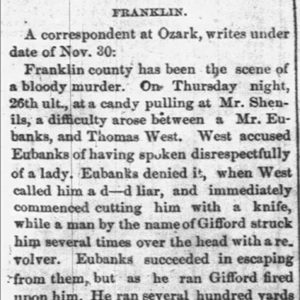

Eubanks Murder Article

Eubanks Murder Article

Eubanks Murder Article

Eubanks Murder Article

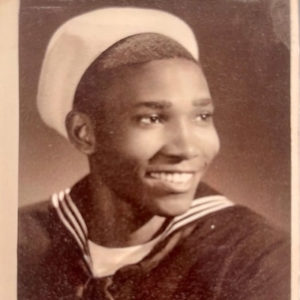

Eugene Ellison

Eugene Ellison

Evans, Timothy C.

Executions of April 2017

James Fagan

James Fagan

Fairchild, Barry Lee (Trial and Execution of)

Fairchild, Hulbert Fellows

Farmer, John (Lynching of)

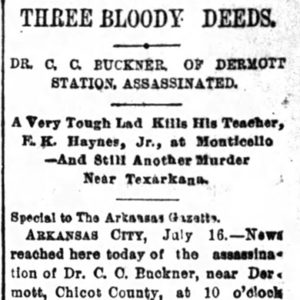

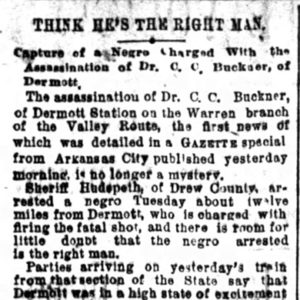

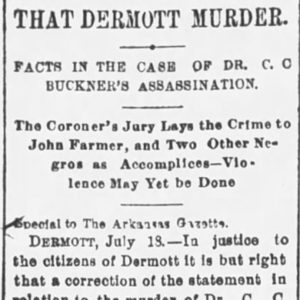

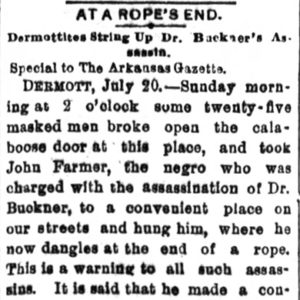

John Farmer Lynching Article

John Farmer Lynching Article

John Farmer Lynching Article

John Farmer Lynching Article

John Farmer Lynching Article

John Farmer Lynching Article

John Farmer Lynching Article

John Farmer Lynching Article

Farrar, Clayton Ponder (Clay), Jr.

Faulkner County Sheriff Monument

Faulkner County Sheriff Monument

Fayetteville Federal Courthouse

Fayetteville Federal Courthouse

Featherstone v. Cate

Federal Correctional Institution

Federal Correctional Institution

Feild, William Hume “Rush” Sr.

Fendler, Oscar

Feuds

Filmore, Isaac (Execution of)

Finney v. Hutto

aka: Hutto v. Finney

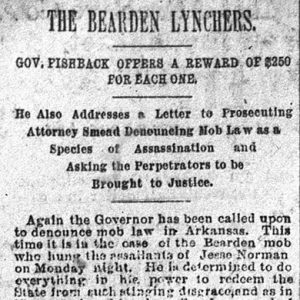

Fishback Lynchings Letter

Fishback Lynchings Letter

Fleming, Sam (Lynching of)

Fleming, Victor Anson (Vic)

Flemming, Owen (Lynching of)

Flowers, William Harold

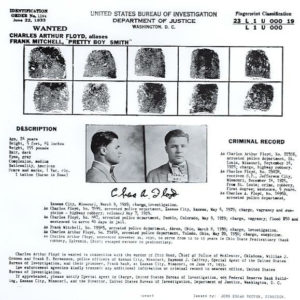

Floyd Wanted Poster

Floyd Wanted Poster

Flynn-Doran War

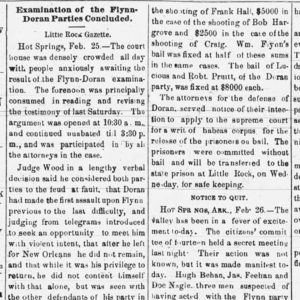

Flynn-Doran War Story

Flynn-Doran War Story